The Age of the Volunteer Firemen laid the groundwork for cultural traditions in the Fire House, but the early career Fire Departments would set the customs and initial work schedules that still impact today’s Fire Service. As has been covered in the chapter on “Irish-American Firefighters”, the ethnic culture of early career Firemen was responsible for establishing some of the traditions found in the Fire Service today. This chapter will continue examining the circumstances and work conditions that helped shape the early career Fire Service. First, we need to review a brief history of the establishment of the first career departments in the United States.

As may be recalled from the chapter on “The Age of Steam Fire Engines”, Cincinnati, Ohio, was the first city to establish a career fire department on April 1, 1853.1 The change from a volunteer fire force to a career department was precipitated by a major fire in town that was poorly handled by the volunteer fire companies. During the response, the hand engines and hose companies fought over the closest fire hydrant, which quickly escalated into a brawl while the fire went unchecked, greatly upsetting the Mayor and City Councilmen.2 In addition, the creation of the first practical steam fire engine by Shawk and the Latta Brothers in 1852 in the City of Cincinnati itself provided an efficient, low manpower answer to staffing a full-time Fire Department. The new career department consisted of over 400 personnel staffing fifteen Fire Companies (consisting of steam and hand pumpers), one Hose Co., and one Ladder Co.3 The initial step had been taken that would significantly change the United States Fire Service. The City of Cincinnati would lead this change as the first all-paid fire department. Continuing to be a leading innovator, the Cincinnati Fire Department (CFD) would become the first to institute all steam fire engine companies when, in 1863, they retired their last hand-pumper.4

On a different historic note, some references list Boston, Massachusetts, as the first paid Fire Department in the American Colonies. The city bought a “Newsham” hand-engine from England and in 1678 appointed Thomas Atkins as Chief Engineer, who was authorized to appoint 12 assistants. Early documents note that they were “to be paid for their pains about the worke.” 5 There is some dispute as to whether they ever received any remuneration for their “worke”. Though they were paid Firemen, they were paid on call, not full-time Firemen. So from this perspective, Boston was not the first career-staffed Fire Department.

Firemen Responding to Fire Alarm. Photo author’s collection.

Within eleven months of Cincinnati, the Providence Fire Department in Rhode Island became the second career Fire Department on March 1, 1854.6 Providence faced similar issues with Volunteer Fire Companies as had Cincinnati. However, the city kept hand engines for a while longer, switching to using draft hand engines to eliminate the need for bucket brigades for water supply, thus reducing manpower needs. Steam fire engines would initially be added in 1859 and finally replace all hand pumpers by 1867.7

St. Louis, Missouri, would become the next career Fire Department in the United States. Perhaps following Cincinnati’s lead, St. Louis purchased their first steamers (three) from the Latta brothers in 1857, with the City Council passing an ordinance establishing the City Fire Department that same year.8

New York City has been used in this historical series as a leading example of a progressive city regarding fire protection and firefighting practices. And there is no doubt that they earned that reputation. However, they did not establish a career Fire Department until 1865. As covered previously, at the end of the Civil War, the New York state government enacted a law to create “a Metropolitan Fire District (MFD) and Establish a Fire Department Therein.” (Footnote: 9) This included Brooklyn’s east and west divisions and replaced the problem-plagued volunteer fire companies, establishing the M.F.D. Because of the war, the volunteer departments in New York were short on man power, having trouble turning out on calls, and were politically mismanaged. The replacement of volunteers actually took until 1869, and in 1870 the city regained control of the fire department from the state and changed the name to “Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY).”10

New York Volunteer Fire Companies had already begun using steam fire engines before the move to a career Fire Department. With the change to a career department, additional steam engine companies were added. In 1865, the Board of Metropolitan Fire Commissioners authorized the procurement of an additional ten “second-class” steam fire engines from the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company.11 Additionally, in the transition from Volunteer Fire Companies to the MFD, a number of volunteer companies were disbanded, some fire houses sold, and others remodeled, along with the appointment of new or existing Firemen into career positions.

Early Civil Service Positions

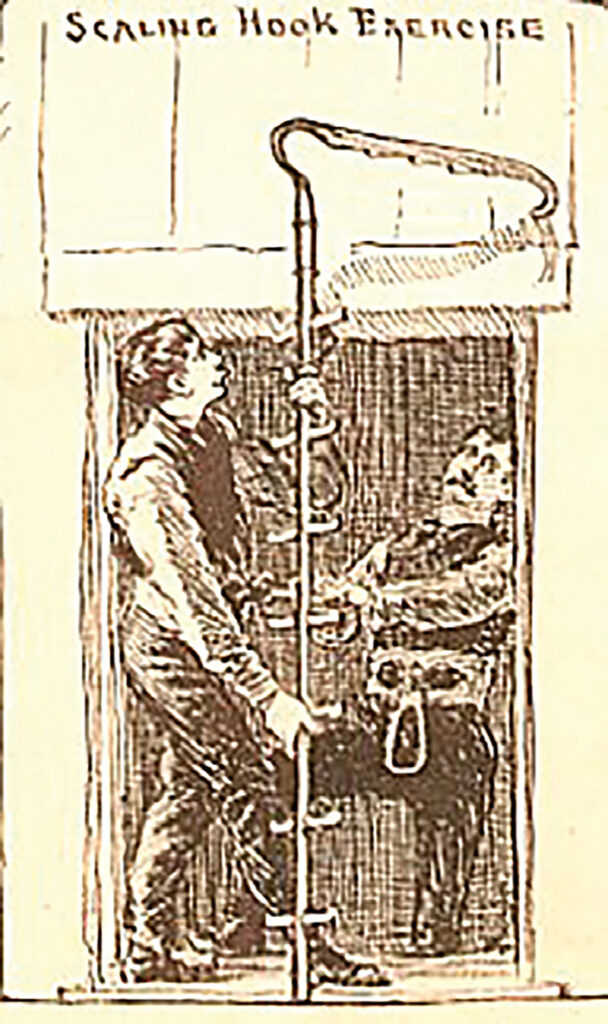

As cities added these new career (paid) positions to the city’s roster of jobs, they instituted new rules and regulations that specified the type of applicant who was required to perform the job. Historic documents from New York City provide an example of early civil service rules for Firemen. In 1898, New York Civil Service Commission Regulations required Fire Department applicants to have signed affidavits from references that the applicant was “a man of good moral character” and “of sober and industrious habits”. The applicant also could not “be guilty or convicted of any criminal act”, and that “he is not a keeper of a liquor saloon.”12 Apparently, bar owners were not held in high esteem by the citizens of the time period. A physical exam standard was applied to the civil service hiring process in most cities. In 1891, New York tested applicants on physical and rescue skills, including climbing and balance tests, Fireman carry, and scaling ladder (pompier) exercise.13

Though quite a number of the Volunteer Firemen went on to apply for jobs with the new career Fire Department, many local businessmen and tradesmen of the community did not want to give up the businesses they had created and with which they had prospered. For it would be found that the new career departments would require a demanding and austere life. A number of the first career Fire Chiefs looked to the military for work models, and the duty of career Firemen was based on the stringent military service of the day. In addition to the requirement to risk one’s life on an almost daily basis, in the early days of the career-departments, like New York, Firemen were required to always be on the job with the exception of a meal break at home each day and one day off each week.14

Providence (RI) Fire Department also started with a single platoon that had an around-the-clock duty assignment every day, similar to the military. The Firemen had two days off a month and mealtimes away from the station.15 However, like other departments, should a fire call occur, their leave time was canceled. Providence Deputy Assistant Chief (Ret.) Curt Varone shared with the author an interesting insight regarding Firefighter seniority. The senior Fireman got their choice of mealtime off. A rotation of senior personnel to rookie Firemen followed, with the new man sometimes left to eating lunch at 9:00 AM or 4:00 PM.16

With many Volunteers declining to seek full-time positions, these new career positions, despite the work conditions, were attractive jobs for the swelling immigrant populations in the United States at the time. For a review of immigrant impact on the Fire Service, refer to the chapter on “Irish American Firefighters and Bagpipes”.17 The Celtic immigrants, especially, would further shape the culture of the Fire Service through ethnic family practices.

Pay and Benefits

The remuneration or pay of the early career Firemen varied by department, but this section will use the Metropolitan Fire Department (MFD) of New York as an example. A published article in the New York Times in 1865 listed some expenses of the new MFD, including personnel costs. Fire Companies were composed of twelve men. The Fire personnel were paid an annual salary. The company Foreman (Captain) salary was $800, and the Assistant Foreman (Lieutenant) had a salary of $750. The steam fire engine engineer’s salary was $900, amazingly more than the Company Foreman’s. Perhaps this was because of the technical expertise required of the steam engine operator. Drivers (Teamsters) were paid $700, along with the Privates (Firemen).18 In comparison, the average carpenter’s wage in 1860 in New York was $1.62 per day or about $507 per year.19 Though the carpenter made less, they could go home to family and had each night to themselves.

By 1913, salaries in the Fire Department of New York had risen to $1,000 per year for a Probationary Fireman, and with promotions to a 1st grade Firemen a salary of $1,400 per year. Engineers were paid $1,600 and Captains $2,500 per year.20

Early on career Firefighters not only served in difficult and austere conditions, but they had few benefits and little to no relief protection should they be injured on the job. Though the Fire Department administration might try and find limited duty assignments for injured Firemen, there was no official guarantee. As an example, St. Louis Firemen served in hazardous situations with only a volunteer charity fund to provide for relief in case of injury or death. Finally, in 1893, Missouri legislation provided for municipalities to establish Pension Funds.21

By 1913, most departments had established benefits that included free medical care by the Fire Department Doctor and a modest pension. Firefighter gear was provided in some Fire Departments, but generally, personnel were required to pay for their own uniforms and protective gear. While some departments provided bed linen and laundering, in other departments, the expense was on the Firefighter.22 It should be mentioned for consideration that with the continuous duty schedule, the unmarried personnel had no cost lodging in the Fire House six nights out of seven each week.

Living at the Fire House

Though living at the Fire House for some new career Firemen may have been a novel concept, the practice actually began during the “Age of the Volunteer”. The development of the first hand-pump engines quickly created the mystique of the Volunteer Firemen and the first Fire “Enjine” (Engine) Companies in the early American Colonies. Camaraderie and Esprit de Corp, of the community’s Volunteer Firemen was high, and competition to be first on a fire was a major goal. Many Firemen started sleeping or “bunking” at the firehouse, at least several nights a week.23 First, from simply sleeping beside the “enjine” in cramped quarters, to converting upstairs meeting rooms or recreation halls into bunkrooms. This practice would escalate with the adoption of the first steam fire engines and the need to maintain house boilers and later horse teams as part of the new methods of fire response. Even the Fire House seemed to be adapting to the coming cultural change to the Fire Service and the first full-time staffed Fire Stations.

Though some of the Volunteer Fire Companies had outfitted their Fire Houses with minimum bunkrooms and a few had kitchens, many did not, or were insufficient for the transition to career Fire Service occupation. In houses with two companies (engine and hose or ladder), there was an average of twenty personnel on duty. The changes in personnel and equipment required the renovation of existing Volunteer Fire Houses or the building of brand new ones.

With the move to career Firemen, the new steam fire engines, and horses to pull the apparatus, more space was required in the Fire House or Station. The densely packed urban environment of most cities caused land to be at a premium, and Firehouses were constructed with apparatus and horses occupying the first floor, and Firemen occupying a second floor.24 Of course, in most multi-story Firehouses after the 1890’s, one finds the presence of the ubiquitous fire pole or sliding pole to quickly get from the upstairs bunk rooms to the apparatus floor. For more information on Firehouses and fire poles, see the chapter “Fire Poles, A Historic Tradition in the Fire Service”25

The Firemen were provided sleeping quarters in large dormitory-style bunk rooms. The Company Officers, and if a Chief Officer was assigned to a house, were quartered in individual rooms that served as both bedroom and office space for them.

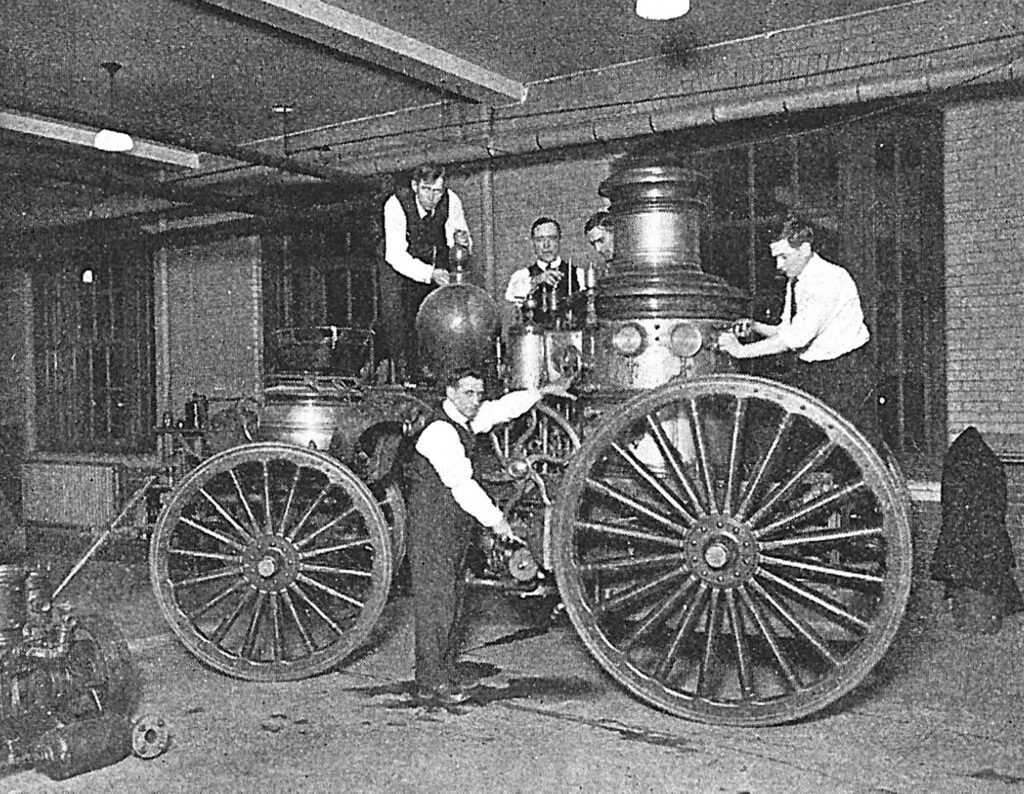

In addition to normal station duties, Firemen rotated standing a watch period at the Firehouse watch desk located in the apparatus bay, usually near the front doors. The common practice was to divide watches into four-hour periods. Though Drivers (teamsters) saw to the well-being of the horses, the Probationary or newer Firemen usually were responsible for mucking out the stalls and feeding the horses. Various fire apparatus required special care, such as steam fire engines, which required cleaning, lubrication, and servicing of the pump, and resetting and prepping the boiler and fire box after each fire. Leather fire hose required cleaning, lubrication, and hanging to dry while fresh hose was loaded on wagons or reels. For more information on Firehouse care and maintenance of early apparatus and equipment, see previous chapters in this series.

Initially, meal furloughs once a day were allowed so Firemen could go home to eat. Probably, this practice originated due to limited kitchen facilities in the originally acquired Volunteer Firehouses. Unlike the military, these new Fire Platoons had no commissary (cafeteria) to provide meals for the troops. Sometimes Firemen used runners (neighborhood boys) to pick up meals for them at local eateries or from local homes, for which they paid the runner. Later, with renovations and kitchens added, Firemen began cooking meals in the Firehouse.

Some cities provided their Firemen transit passes that allowed them to ride for free on city street trolleys or inter-city railways. This provided transportation for the Firemen to home if not living nearby their Firehouse, travel to other station assignments, or other fire department facilities (i.e., training academy or headquarters)

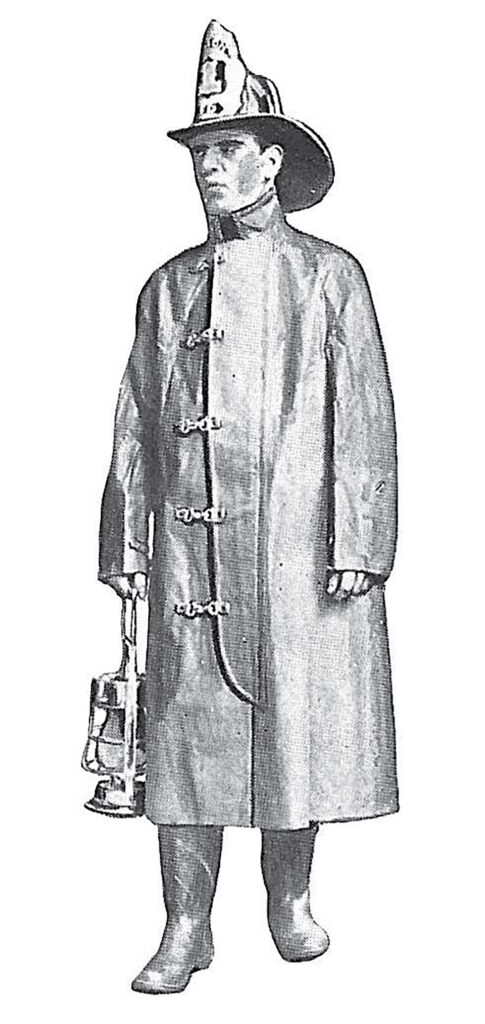

Uniforms and Fire Fighter Gear

Uniforms

The iconic “red” shirt that identified Firemen came into vogue during the 1840’s with the Volunteers, and quickly spread across the American Fire Service.26 As career fire departments began to be instituted, the tradition of the red shirt carried over to the full-time firefighters. New York’s Metropolitan Fire Department (MFD) rules and regulations of 1865 required the firemen to wear uniforms as follows: “Chief Engineer and other Engineer officers (chiefs) were instructed to wear a red flannel, double-breasted shirt, dark blue pilot cloth coat (knee length), vest and pantaloons of the same material, blue cloth cap and white fire hat.”27 In 1868, the “General Orders” changed the uniform requirements with chief officers wearing white shirts, while “red shirts then became part of the uniform for the company officers, with firemen and engineers of steamers continuing to wear blue shirts.”28 Later, Fire Departments would standardize on a dark blue color for all Firemen, perhaps achieving a more military look. Fatigue or garrison caps would become standard headwear when in uniform (the accepted practice of the day for men to wear hats). The cap’s dark blue cloth follows a U.S. Navy pattern with a short black patent leather visor. Rank insignia or badges were traditionally worn on the cap.29 Later, the hat location for badges and rank would transition to the coat badge and coat or shirt collar for rank insignia.

Fire Fighter Gear

The practice of sleeping (bunking) in the Fire House by Volunteer Firemen began the custom of wearing oversized pants that would allow the cuffs and pant legs to slip over the tops of high-topped boots. This allowed the Volunteers at night to quickly dress for a fire response. This practice led to the term “bunker pants” or later “bunker gear”, a term that is still commonly used by more senior aged Firefighters today. In some areas of the country, the term turnout gear is used for Firefighter gear. The origin of the term is similar to bunker gear. The Volunteer Firemen would be said to “turnout” for a fire, thus the extra clothing they would don to fight fire came to be known as “turnout gear”.30 The oversize pants were carefully folded down over loose-fitting leather boots, or later, the first rubber boots, and the awakened Firemen could quickly slip into them and be dressed to respond. The Firemen suspenders are coming about to hold the loose fitting pants up without having to take time to fasten a belt. Some of the career Firemen would come to call this gear a “night hitch” or “quick hitch”.31 Oddly enough, in some departments this resilient type of clothing was usually only worn at night responses, with conventional clothing worn during the day, with perhaps the exception of boots. Of course, for firefighting protective headgear, the iconic Gratacap style leather fire helmet was used, being preferred by volunteers and career Firemen alike. Today, this bunker gear or turnout gear is referred to as Firefighter Personal Protective Clothing or Firefighter PPE.

Traditionally, for protection from the heat of fire and the cold weather in winter, the early Firemen wore wool or leather coats. Wool was a fairly durable fabric that retained body warmth even when wet. By the late 1800’s, there would be a new change in firefighting equipment.

Rubber Boots and Coats

The Practice of using natural rubber in the Fire Service came when James Boyd of Boston, MA, made the first rubber-lined cotton fire hose. He received a patent in 1821 and went on to improve the product.32 By the 1890’s, numerous companies were producing and selling rubber-coated products, including rubber-coated items designed for Firemen. These items included rubber-coated canvas coats and rubber pull-up hip boots.33

Fire Company Assignments

Within the new career Fire Departments, personnel were assigned to tactical fire companies housed in designated Firehouses. These were the days before combination pumpers or multi-purpose apparatus. Generally speaking, each fire company or piece of apparatus had a specific tactical assignment.

Perhaps the most common in most cities was the Engine Company, which was responsible for staffing a steam fire engine that pumped water from a water supply to the scene. The Steam Fire Engine Co. was composed of an officer, driver (teamster), engineer, and stoker. In some cities, they also had Chemical Engine Companies, providing self-contained quick attack capability beginning in 1872.34 For more information on Chemical Engines, see the chapter on “The Chemical Fire Engine”.35

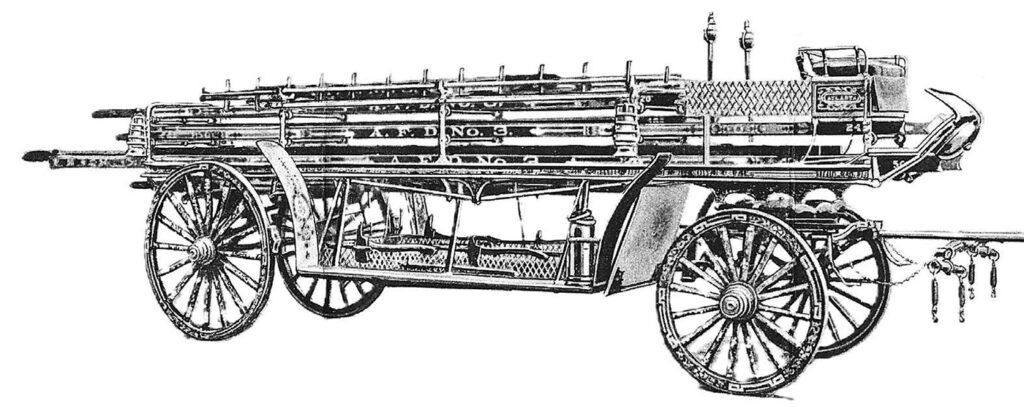

Working with the Engine Company was the Hose Company that carried fire hose on reels or wagons to be used for attack lines attached to the steamer (engine) or supply lines to supply water to the engine. In addition to helping the engine establish a water supply, the Hose Co. Firemen were responsible for stretching the line to the fire and for firefighting. They might also perform immediate rescues, etc. Some hose companies might carry some ground ladder or pompier (scaling) ladders for initial rescue operations. This was the beginning of multi-function or combination apparatus that would lead to triple combination pumpers and finally to todays “quints”.

Ladder companies carried ground ladders and sometimes were equipped with hand-cranked aerial ladders attached to the ladder wagon. Some ladder apparatuses were “Hook and Ladder” Co. that carried large hooks as well as ladders. The hooks were used to pull down burning walls and roofs to prevent fire spread and create fire breaks during conflagrations. The Firemen assigned to the ladder company performed similar tasks that modern ladder companies do: ladder work, ventilation, rescue, and forcible entry.

Larger cities might have specialty companies such as water tower apparatus, salvage companies, or other specialized units. In some larger cities, insurance companies sponsored private salvage companies to preserve and protect property and contents.

Development of Station Duty and Platoons

As most people would agree, the Fire Service is a unique occupation that is driven by its mission of saving lives and property. Because of the potential for emergencies (fires, rescues, medical calls) to occur any time, day or night, the Fire Service is always ready to respond 24-hours a day, every day. To enable this continuous coverage, Fire Departments, whether career or volunteer, establish duty assignments for their personnel to ensure there is a workforce ready to respond when needed. Though Volunteer Firefighters can serve assigned shifts in the Fire Station, they usually are dispatched by radio/pagers/texts from home, business, or other activities to answer emergency calls. Other duty assignments, such as station and truck maintenance, training, and special assignments, are scheduled events around the volunteers’ job and personal life. This is similar in some respects to the early days of the volunteer era in Colonial times. Career Firefighters are employees of the Fire Department; they work for and are generally assigned to a platoon, which has a regular shift schedule of work assignments. During their shift, they will answer emergency calls, perform station and truck maintenance, do training, and perform special duty assignments. And depending on the length of their assignment have meal times and sleep periods when not on emergency calls.

In the Fire Service, a “platoon” is defined as “a shift of firefighters assigned to work the same tour of duty.”36 Today, many Fire Departments use the term shift to identify a work shift, such as A-shift, B-shift, etc., instead of platoons. The term platoon originated in the 1600’s and refers to a small grouping of soldiers performing assigned tasks.37 Thus, the term further linking Fire Department organization to military units of the time period. The military division of troops ranging from small units to large units might be called a squad, platoon, company or battalion. In the early Fire Service Firefighters were assigned to a company (i.e., engine company, or ladder co.), a station, and in larger departments, the stations might be grouped into geographic Battalions or Districts all assigned to an operational duty period called a platoon or shift. In other words, when the career Firefighter is off-duty, another Firefighter takes their place on-duty to provide around-the-clock staffing each day. This section will examine the historical development of shift schedules in the career Fire Service.

Assumed to be in the public domain.

A majority of Firefighters today probably think the 24-hour shift rotation was the traditional standard for the United States Fire Service. The more seasoned Firefighters probably remember a two-platoon system with the On 24 hr. /Off 24 hr. continuous rotation. The author’s first full-time Fire Service assignment in the mid 1970’s had this shift schedule. One was getting up every morning to either go on-duty or go off-duty, generally serving 15 shifts a month. Thankfully, benefits and work schedules have improved over time, adding “Kelly Days” or a third platoon to have different combinations of 24 hour shifts separated by various combination of days off to give Firefighters time to recuperate from difficult or demanding shifts. However, the traditional 24-hour shift was not the original work schedule for the early career Fire Departments.

Though Cincinnati and Providence Fire Departments started a career department before the American Civil War (1861-1865), New York and the other career departments soon followed this trend at the end of the war. Governing officials saw these new departments as being similar to the town’s militias of the past, personnel on a military duty assignment. In the case of a fire department assignment, the personnel were providing the citizens protection from fire instead of a hostile military force. Just like soldiers in a time of conflict, the fire forces needed to be on duty all the time. The first career Fire Departments were based on this quasi-military duty model.38 An example of military-style leadership is seen in the early days of the Metropolitan Fire Department (MFD), which would become the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), with the appointment of retired Civil War General Alexander Shaler as President of the Board of Commissioners in 1867.39 Using his military background, Shaler would change the structure of the fire department along military lines, and even change the titles of Foremen and Assistant Foremen to military titles of Captain and Lieutenant, respectively.

The Firemen were considered public servants, filling an occupation that required them to be always on duty. There was a single platoon of men assigned to each station. As an example, New York Firemen basically lived in the Fire House to which they were assigned. They worked 24 hours a day each day, with the exception of a meal break each day, and a 24-hour leave three times a month.40 Meal breaks and leave days varied between career departments of the period but followed a similar work schedule.

This work schedule, established and implemented by most of the early career Fire Departments (and those that followed), made for an austere and demanding life for the Firemen. It is an odd twist of circumstances when one considers that originally one of the reasons given by supporters for a “paid” fire department was because the volunteer “firemen sleep or ‘bunk’ at their respective engine houses. This cuts them off from all home or virtuous female influence.”41 Ultimately, this is what the political officials created with a full-time Fire Department encumbered by a work schedule that created a para-military work force practically devoid of a normal home life.

Multiple Platoon Systems

Eventually, in the late 1800’s, Firemen, some Fire Chiefs, and citizens began to push for better working conditions for their municipality’s Fire Department, giving them more time off for family life. Enter the concept of the two-platoon system. This idea of a new work shift paradigm began to circulate in national Fire Service conferences and meetings of the day.

New York Fire Chief Edward Croker implemented a trial experiment of the two platoon system in the winter of 1904-05 in one of the department’s battalions.42 The companies were split into two platoons or shifts. Officers were transferred to provide leadership for each shift. But the shifts would not be working a rotating 24-hour shift. One shift worked ten hours from 8:00 am to 6:00 pm, the other fourteen hours from 6:00 pm to 8:00 am. Every two weeks, they would swap shifts. However, it seems Chief Croker may not supported the experiment or the concept of two platoons. Off-duty meal breaks were eliminated, and most significantly, the beds were removed from the firehouses. The night shift was expected to stay up all night, ready to respond to emergency calls. Lack of sleep during the night and little time to do anything but try to catch up on sleep during the ten hours off soon affected performance and attitudes. A Board of Underwriters report stated that the two platoon system was “extremely detrimental to the efficiency and discipline of the department and unsatisfactory even to its advocates among the privates [Firemen].”43 After the trial, the battalion went back to the regular on-duty schedule. Though Chief Croker was an innovative fire chief of the time period, promoting new building and life safety codes, when it came to the work schedule, he was apparently a traditionalist to maintain the current system. Even Chief John Kenlon, who became Fire Chief after Croker in 1911, was against a two-platoon system. In his book Fires and Fire Fighters, he wrote that the “esprit de corps – a vital force in fire-fighting – will vanish,” referring to the consequences of going to a two-platoon system.44

Putting aside tradition and disruptive concerns for the system, the major issues related to the adoption of a two-platoon system at the time were the cost of manpower and efficiency. By adding platoons or shifts of men to cover the off-duty platoon, the operational cost of the Fire department significantly increased to pay for the second platoon of added personnel. If the Fire Department elected to split the existing force into two platoons, the number of personnel working each shift was reduced, which jeopardized efficiency by operating with too few personnel on a shift.45 The physical and mental well-being of the firefighters was, at the time, a secondary issue to budget expense. This was well before federal regulations were created regarding wages and overtime requirements.

Documents indicate that up to World War I, most career Firefighters of paid departments were on a one platoon system working a continuous duty shift that provided minimal time away from work.46 However, the concept to change Firemen work hours was gaining steam. Between World War I and WWII, the United States saw a shift by Fire Departments to “some form of two-platoon system.“47

Pittsburgh, PA, went to a two-platoon system in late 1916. It was similar to other first attempts with two shifts, a day shift of ten continuous hours and a night shift for fourteen continuous hours. Splitting the current force into two shifts, it created a problem of trained personnel ready to move up into engineer and assistant engineer positions. This required a special training program to prepare current firefighters to meet civil service requirements for the positions.48

Labor Unions would also come into play during this period. The International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) was formed in 1918 and was chartered by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) unions. At their first convention, they began to advocate the need for a two-platoon system.49

In February 1918, Cincinnati Firefighters organized a local union under the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF).50 In April of 1919, the Firemen went on strike for improved work schedules, fair wages, and better conditions. The city broke the strike shortly after, but a year later, the CFD started operating on a two-platoon system.51 This may have been precipitated by the department’s move to mechanization, thus releasing personnel from horse duties and freeing them to form another shift. In 1952, the CFD went to a three-platoon system, creating a 24-hour on and 48-hour off working structure.52 Today, after working seven on-duty tours, Firefighters received a Kelly Day off.53

The Providence (RI) Fire Department (PFD) instituted a two-platoon system in 1923. The department adopted a ten-hour day shift and a fourteen-hour night shift that changed assignments each week with a twenty-four hour shift change day on Sunday.54 The City Council would rejected the change because of the resulting increase in the Fire Department’s budget due to the need to add approximately 100 personnel to fill the shift assignments. However, they relented within a month, and the two-platoon system became a reality. In 1947, the PFD reduced the work week hours and provided for 48-hour leave every ten days.55 In 1955, the Fire Department implemented a three-platoon system, and in 1971, went to a four-platoon system, each change further reducing duty work hours.56

After the end of World War II (1945) and into the 1950’s, the two-platoon system became a standard operational duty assignment for Firefighters in the United States.57 Though some departments were still using 10/14 or 12/12 hour daily shift schedules, the common shift rotation for most Fire Departments had become the 24-hour shift rotation.

Labor issues and remuneration became a national concern for all workers in the United States in the 1930’s. In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) into law as part of his “New Deal” plan.58 It primarily addressed child labor regulations, a minimum hourly wage (25 cents per hour), and set a maximum work week (44 hours).59 However, state and local governments were exempted from the Act. Congress amended the FLSA in 1974 to include state and local governments. Congress created the “207K” exemption in the FLSA to address the unique work schedules that Firefighters and Police Officers worked. After much legal wrangling and federal lawsuits, in 1985 the Supreme Court ruled that the FLSA did apply to state and local governments.60

The results of these Acts and Regulations impacted Firefighter work schedules related to when and how overtime remuneration was due. These federal regulations became a consideration when adjusting Firefighter work schedules and the amount of potential overtime pay that could impact budgets.

Over time, considerations for both Firefighter work/life balance and overtime expenses have brought about a variety of platoon and shift work schedules. Some Fire Departments instituted a three-platoon system with a variety of shift schedules, such as 24 hours on/ 48 hours off; or 48 hours on/ 96 hours (4 days) off. Other, more complex rotations are optional with “Kelly” Days added. A Kelly day is an off-duty day in addition to regular off-duty shift days.61

In recent years, some Fire Departments have gone to a four-platoon systems providing additional shift rotation options and more time off. An example of a four-platoon shift might be 24 hours on and 72 hours (3 days) off. More complex rotations are also used by some Fire Departments.

Though the job of the Firefighter can still be as arduous as it once was, the work-hour demands have changed over time. The Fire Service is still a para-military organization that encompasses a chain of command, discipline, teamwork, and mission-focused training and deployment to manage potentially hazardous public safety/service tasks. However, it has become more flexible and work/life balanced in the ways the tactical personnel are assigned to work. The goal of modern platoon and shift schedules is to balance work with adequate rest for Firefighters while minimizing overtime, which would impact the operational budget of the Fire Department. In addition, other benefits, such as educational incentive programs, have further incentivized and professionalized the Fire Service. These various initiatives provide a positive impact that will improve the longevity and contribution of the personnel. Leaving a lasting legacy for those generations that follow.

Changing Culture and Traditions

The early career Fire Departments began with round-the-clock staffing by a single platoon of Firemen. Like their military counterparts of the period, they served an austere duty life with limited time off. Firemen were granted meal breaks on a seniority rotation basis. Also, they received one or two 24-hour days off (furlough) during a month of otherwise continuous service. It was an extremely hard and demanding life. However, veterans coming out of military service from the American Civil War, along with others desperate for a secure living wage job were willing to step up and apply for these new civil service jobs. In addition, the admiration of the citizens for the heroics of the brave Firemen garnered in the volunteer days was extended into the career service, making the job a respected profession (for the most part). But besides the potential risks of injury or death, the austere work life would lead the Firemen and citizens to seek better working conditions (life/work balance) for the Fire Departments’ workers.

As all things do, over time, things changed in the Fire Service. Where the practice of dormitory-style sleeping arrangements in the Fire House was the norm, many new Fire Stations being constructed today have individual rooms for each Firefighter. Certainly giving more personal privacy, but perhaps losing some of the camaraderie of the shared bunkroom. The Firehouse kitchen table, where so many communal meals were shared along with work discussions, family, and politics, is changing to meals in the dayroom and personal e-communications. Even the tailboard discussions in the apparatus bay seem to have gone the way of so many other customs. Though these changes reflect our newer generations’ lifestyle and work habits, it is not necessarily bad. Firefighters now have personal space to mentally process tough calls, or quiet time for study to prepare for new opportunities or keep abreast of new changes in technology. New shift schedules now give Firefighters more time for family and to relax between hectic on-duty days or difficult, taxing emergencies. Though new federal regulations creating overtime costs were one factor in driving work schedule changes, the need for improved mental health and better life and family relationships have greatly benefitted from work schedule changes.

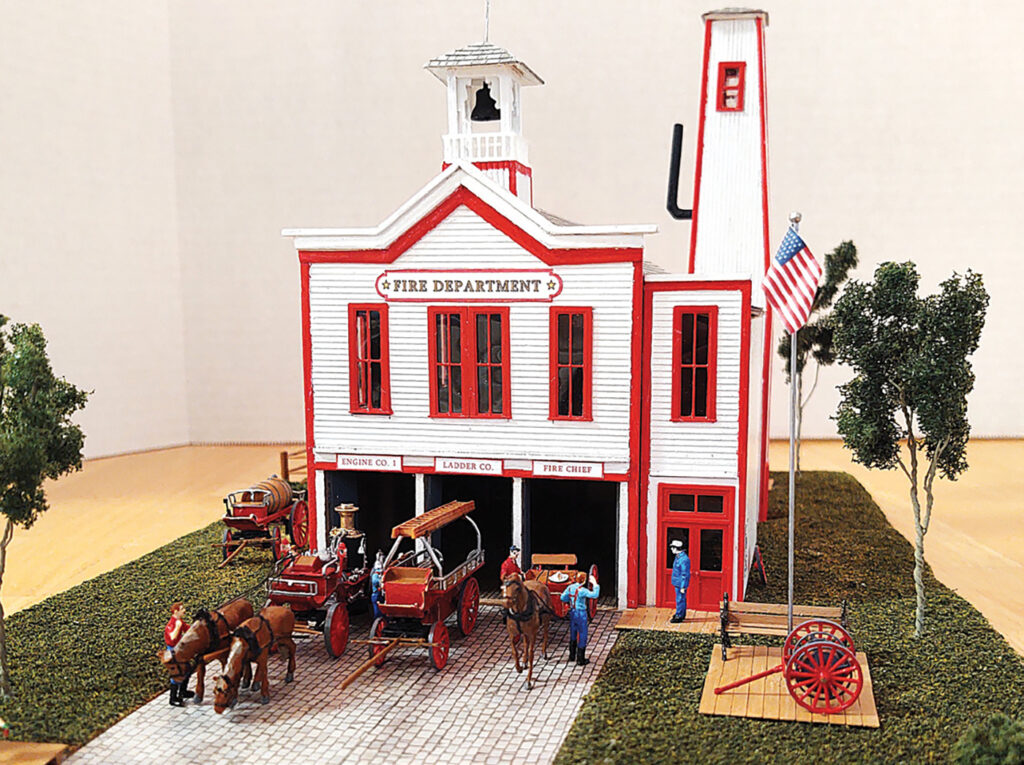

Still, some of us sometimes mentally wander back to the historic past. The kerosene lantern lit rooms, the smells of the apparatus bay with smoke-stained leather hose, liveried horses, and coal furnaces preheating the steamer’s boiler. Along with this, the kitchen fragrances of homespun hearty meals simmering on the Firehouse stove. Trusted compatriots gathered in the recreation room whiling away the time with dominoes, parlor games, or craft projects. Suddenly, the house gong sounds and taps out a box number. Everyone is off in the instance down the poles and to their horse and harness tasks, mount the apparatus, and off on another fire response. All performed in under 20 seconds! Long days and nights, combined with sometimes difficult emergency calls shared with a close-knit Firehouse Family, established a strong culture and tradition. It must have been one heck of an experience to live through those days of brave, dedicated personnel, strong horses, and fiery steamers all working together to protect life and property.

The desire to serve continues to permeate the Fire Service today just as in the past. However, over time, the difficulties of the Firefighter’s life also drove a desire for change. Just like families wanting a better life for their offspring, Firefighters sought to make a better profession for the generations that followed. Though these changes have modified how we do the work, past traditions still mold and inspire the career or avocation today.

The Fire Service continues to make improvements in technology, safety, and the well-being of those who serve. These continuing changes will improve the longevity and contribution of the personnel in our profession and leave a lasting legacy for those generations that follow. As we embrace the changes that continue to impact the Fire Service, remember our dedicated forefathers who laid the foundation of our proud Fire Service profession.

Model and photo by author.

Authors Comments

The author wishes to recognize and thank the fire service personnel and organizations for their assistance in the development of this chapter. In particular, the author expresses his appreciation to: Curt Varone, Deputy Assistant Chief (Ret.) Providence (RI) Fire Department and Attorney and author Fire Law Blog, Exeter, RI; Michael A. Washington, Sr., Fire Chief (Ret.) Cincinnati (OH) Fire Department, and the University of Missouri Ellis Library/Lending Library for assisting the author in obtaining the inter-library loan of various research documents and archival materials.

The author also wishes to recognize all the various Historians and Authors for their extensive and invaluable work in Fire Service History through artifact notes, articles, and books that have been used for research purposes by the author and footnoted in this series. May their work continue to endure the ages and preserve the true history and traditions of the American Fire Service.

The A Part of Fire Service History Series articles are copyrighted © 2023 – 2026 by the author and are published under permission granted to the FFAM.

Endnotes

- Christine Mersch and Lisa Mueller, Images of America Cincinnati Fire History, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina, 2009, p. 7.

- W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, Fire Buff Publishers, New Albany, Indiana, 1997, p. 14.

- “Paid Fire Department 1853”, CFD History.com, 2024, web article accessed Dec. 20, 2025: http://www.cfdhistory.com/.

- Christine Mersch and Lisa Mueller, Images of America Cincinnati Fire History, p. 8.

- John V. Morris, Fires and Firefighters, Bramhall House: New York, 1955, p. 24.

- Patrick T. Conley and Paul R. Campbell, Firefighters and Fires in Providence, A Pictorial History of the Providence Fire Department 1754-1984, The Rhode Island Publications Society and The Donning Company/Publishers, Norfolk/Virginia Beach, Rhode Island, 1985, p. 35.

- Ibid, p. 35 & 38.

- W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 220.

- Gary R. Urbanowicz, Badges of the Bravest, Turner Publishing Co., Paducah, KY/M.T. Publishing Co., Inc., Evansville, IN, 2002/03, p. 16.

- Ibid.

- “The Fire Department”, The New York Times, September 28, 1865, p. 5, from the New York Times Archive, https://www.nytimes.com/1865/09/28/archives/the-fire-department-how-far-the-work-of-reorganization-has.html#.

- “Fourteenth Annual Report”, New York City Civil Service Commission, Regulations and Classifications for the New York Civil Service, The Martin B. Brown Company, Printers and Stationers, New York, 1898, p.127.

- W.P. Snyder, Artist, “Civil Service Examination for New York Firemen”, Harpers Weekly, Vol. XXX, No. 1555, 1891, p. 656. Smithsonian Institute archives.

- Terry Golway, So Others Might Live, A History of New York’s Bravest, the FDNY from 1700 to the Present, Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group, NY/NY, 2002, p. 4.

- Patrick T. Conley and Paul R. Campbell, Firefighters and Fires in Providence, A Pictorial History of the Providence Fire Department 1754-1984, p. 53.

- Curt Varone, Deputy Assistant Chief (Ret.) Providence (RI) Fire Department, Attorney and author Fire Law Blog, Exeter, RI. From an email exchange between Deputy Chief Varone and the author on historic work schedules for early career Fire Departments.

- David E. Hedrick, “Irish-American Firefighters and Bagpipes, A Part of Fire Service History”, FFAM Magazine, Fire Fighters Association of Missouri, Warrensburg, MO, March/April 2025, Vol. 68, Issue 2, p. 8,10, 12, 14, 16, 32-40.

- “The Fire Department, How Far the Work of Reorganization has Progressed”, The New York Times, September 28, 1865, p. 5, through Hew York Times Archives: https://www.nytimes.com/1865/09/28/archives/the-fire-department-how-far-the-work-of-reorganization-has.html#.

- “Pauperism, Crime, and Wages, 1860 by State”, Statistics of The United States, in 1860 of the Eighth Census, Under the Secretary of the Interior, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1866, p. 512. Accessed through University of Missouri Libraries archives Dec. 12, 2025: https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/pricesandwages/1860-1869.

- John Kenlon, Fire Chief FDNY, Fires and Fire Fighters, George H. Doran Company, New York, 1913, p. 255.

- John D. Brewer, Executive Director, “How We Got Here – A Brief History of The Firemen’s Retirement System”, St. Louis Firefighters Local 73, January 25, 2024, web article accessed Jan. 2, 2025: https://www.stlouisfirefighters.org/latest-news/how-we-got-here—a-brief-history-of-the-firemens-retirement-system.

- Average of three city groups of Firemen (Privates) from 27 West North Central cities, “Table 2”, “Salaries and Hours of Labor in Fire Departments of 27 West North Central Cities”, Bulletin No. 684 (Vol. IV) of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, July 1, 1938, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1941, p. 14. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/bls/bls_0684-v4_1941.pdf.

- John V. Morris, Fires and Firefighters, p 145.

- Gerry & Janet Souter, The American Fire Station, MBI Publishing Co., Osceola, WI, 1998, p.61.

- David E. Hedrick, “Fire Poles, A Historic Tradition in the Fire Service”, FFAM Magazine, Fire Fighters Association of Missouri, Warrensburg, MO, January/February 2022, Vol. 65, Issue 1, p. 24-29.

- John V. Morris, Fires and Firefighters, p. 63.

- Janet Kimmerly, Editor, Fire Department City of New York, The Bravest, an Illustrated History 1865 to 2002, History from 1865 – 1999 written by Paul Hashagen, Turner Publishing Company, Paducah, KY, 2002, p. 52.

- Ibid.

- “Fatigue Cap”, Fred J. Millers Illustrated Catalog of Fire Apparatus, and Fire Equipment Supplies, New York, 1872, p. 4.

- Paul Hasenmeier, “The History of Firefighter Personal Protective Equipment”, June 16, 2008, Fire Engineering, The Clarion Fire & Rescue Group, 2025, web article accessed Nov. 20, 2025: https://www.fireengineering.com/firefighting-equipment/the-history-of-firefighter-personal-protective-equipment/.

- Ralph Burklin and Robert G. Purington, “Night Hitch”, Fire Terms, A Guide to Their Meaning and Use, National Fire Protection Association, Boston, MA, 1980, p. 125.

- Robert Serio, “History of Boyd & Son Boston, Massachusetts”, Missouri Boot & Shoe Company, Neosho, MO, web article accessed Feb. 2, 2023, https://www.missouribootandshoe.com/james-boyd.html.

- “Rubber Goods”, Catalogue Standard Equipment’s and Supplies for Firemen, Cairns & Brother, New York, NY, 1890, p. 40-41.

- W. Fred Conway, Chemical Fire Engines, Fire Buff House, New Albany, Indiana, 1987, p. 12.

- David Hedrick, “The Chemical Fire Engine, A Part of Fire Service History”, FFAM Magazine, Fire Fighters Association of Missouri, Warrensburg, MO, January/February 2023, Vol. 66, Issue 1, p. 8–12, 44-50.

- Ralph W. Burklin and Robert G. Purington, “Platoon”, Fire Terms, A Guide To Their Meaning and Use, National Fire Protection Association, 1980, p. 139.

- “Origin and history of platoon”, Etymonline, Online etymology dictionary, accessed Nov. 28, 2025: https://www.etymonline.com/word/platoon.

- Terry Golway, So Others Might Live, A History of New York’s Bravest, Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group, New York, NY, 2002, p. 125.

- Ibid, p. 129.

- Ibid, p. 125.

- Augustine E. Costello, Our Firemen, A History of the New York Fire Department, Volunteer and Paid, first published by Costello in 1887, current edition Knickbocker Press, New York, NY, 1997, p. 799.

- Committee Of Twenty, National Board of Underwriters, “Fire Fighting Facilities (Fire Department)” Report of National Board of Underwriters by its Committee of Twenty on the City of New York, N.Y. Manhattan and the Bronx, Washington, D.C., 1905, p. 51. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.legeros.com/history/library/_nbfu/new-york-1905.pdf.

- Ibid, p. 51.

- John Kenlon, Chief FDNY, Fires and Fire Fighters, George H. Doran Company, New York, 1913, p. 336.

- Major General William J. Donovan, Chairman, “Report of Committee on Firefighting Services”, The President’s Conference on Fire Prevention, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C. may 6-8, 1947, p. 3, 4. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.firehero.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/truman-report-1947.pdf.

- Arthur E. Cote, P.E., Editor-in-Chief, Fire Protection Handbook, 18th Edition, National Fire Protection Association, Quincy, MA, 1997, p. 10-4.

- Ibid.

- J.F. Richards, Chief Bureau of Fire, “From Fire Departments, A Course in Engineering for Firemen”, The American City, Vol. XVI, No. 1, January 1917, The Civic Press, New York, p. 64.

- Fire Engineering Staff, “Around The Fire Service–1910-1919, Excerpts from Fire and Water Engineering “, May 1, 1997, Fire Engineering, Clarion Fire and Rescue Group, 2025, web article accessed Nov. 18, 2025, https://www.fireengineering.com/firefighting/around-the-fire-service-1910-1919/.

- “About The Cincinnati Fire Fighters Union IAFF Local 48”, Cincinnati Fire Fighters Union, AFF Local 48, Cincinnati, Ohio, 2020, web article accessed Dec. 20, 2025: https://local.iaff.org/local0048#:~:text=Cincinnati%20Fire%20Fighters%20Union%20Local%2048%20represents%20the%20brave%20fire,(April%201%2C%201853).

- Justin Peter, CFD Historian, “Major Events Timeline”, The Cincinnati Fire Department 1802 – Present, Feb. 18, 2025, web article accessed Nov. 29, 2025: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/67d95fe85b837b65dcae3a76/6814ae32a7eb62a3ded7a14d_CFD%20Know%20Your%20History%20-%20CFD%20-%20L48%20Timeline-1.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Michael A. Washington, Sr., Fire Chief (Ret.) Cincinnati (OH) Fire Department, from a telephone interview with the author on Dec. 23, 2025.

- Patrick T. Conley and Paul R. Campbell, Firefighters and Fires in Providence, A Pictorial History of the Providence Fire Department 1754-1984, p. 74.

- Ibid, p. 90.

- Ibid, p. 97 & 107.

- Arthur E. Cote, P.E., Editor-in-Chief, Fire Protection Handbook, 18th Edition, p. 10-4.

- Jonathan Grossman, “Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938: Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage”, U.S, Department of Labor, Washington, DC, 1978. Web article accessed Dec. 5, 2025: https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/flsa1938.

- Ibid

- Curt Varone, “Origins of the 7K Firefighter Overtime Exemption”, Fire Log Blog, May 31, 2018, © 2025. Web article accessed Dec. 5, 2025: https://firelawblog.com/2018/05/31/origins-of-the-7k-firefighter-overtime-exemption/#:~:text=Answer:%20The%20law%20you%20are,with%20minimal%20impact%20to%20taxpayers.

- Ralph W. Burklin and Robert G. Purington, “kelly day”, Fire Terms, A Guide To Their Meaning and Use, National Fire Protection Association, 1980, p. 108.