A Part of Fire Service History

If a firefighter were asked to name a color that traditionally represents the fire service, they would most likely name the color “red” or perhaps with the additional notation of “fire engine red.” In the United States, the color red is instinctively linked to the fire service. For most older Americans, as they grew up they were used to seeing fire apparatus painted red along with other fire equipment and paraphernalia. Though the color of the local fire department’s apparatus might have varied, most people intuitively think of the color red when referring to fire engines. There is little doubt the color red has become a traditional part of the American fire service.

This leads one to ask the historical questions of when and why the color red became inexplicably linked to the American fire service. As is the case with much of the history of the American fire service’s customs and traditions, the tradition of the color red seems to have been obscured by history. In most cases, oral myths or assumptions have blurred the facts over time. In this chapter, we will examine some of the historical events and circumstances that compelled the color red to be such a predominant part of the traditions of the American fire service.

A quick search of the all-knowing, but somewhat suspect, internet revealed a variety of answers regarding the color red in the fire service. It was found that a number of the postulated theories are in conflict, and provided little in the way of documented facts. Several fire departments’ websites list some brief explanations of how the color red came to represent the fire service. Again, most of these websites have little in the way of historical facts and appear to be based on assumptions or oral myths.

Two conflicting assumptions that were found regarded the price of paint. They are: red was a cheap paint color and therefore it was used to paint the fire apparatus based on low cost, versus, red was an expensive color of paint, and the firefighters spared no expense in painting their fire apparatus. The quality and cost of paint (actually the pigment used to provide the color) varied depending on the period, pigments, and mixture. Historically, red paint could range in price from low to high depending on pigment and the type of paint process used, similar to other paint colors. Though some red pigments were more expensive than others. The cost factor alone does not answer why firefighters would choose red over other colors of paint.

Another myth is that when automobiles came into use they were mostly painted black like Henry Ford’s Model T. Therefore, to stand out among the other vehicles, firefighters started painting their fire engines red. Historic references show that fire apparatus were painted red before the days of the internal combustion engine. So this fire service practice started before the automobile. However, it is true that Henry Ford’s Model T automobile, the most popular and affordable car of its time, came in one color, black, an overall cost savings by mass production, standardizing on one model all produced the same.1

The final assumptions that will be mentioned are related to comparison or symbolism represented by the color red. Part of this is that the flame of a fire is red and therefore the firefighters picked red for their apparatus in emulation of their calling or respect for their enemy. The other is that the red color is a tribute to the strength and blood of firefighters. The red symbolizes the bravery of the firefighters willing to risk their all, shed their blood, to save others. The later theory based on symbolic bravery and shedding of blood may have some historic and religious merit but still does not provide the total answer.

So what color is your fire department’s fire apparatus? Have you ever asked why? This chapter in “A Part of Fire Service History” will delve into the previous myths or oral histories mentioned, and seek to elicit the most plausible answer based on historical circumstances as to why the color red has come to traditionally represent the American fire service.

As a proviso, it needs to be mentioned that today, as in the past, not all fire apparatus are red. A fire department or organization may choose another color based on local traditions or circumstances. In addition, starting in the 1970s, studies were done concerning color and safety related to the visibility of emergency vehicles. The research suggested the use of alternative colors for the fire service (before the standard for inclusion of high-visibility reflective striping) and had some impact on changing the color of emergency service vehicles in some fire departments.

The History of the Color Red

To better understand the use of the color red in the fire service, the origins and utilizations of color will need to be briefly examined. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the color red is “the longest wavelength of light discernible to the human eye.”2 As you may remember from high school physics class, objects absorb some wavelengths of the visible light spectrum while they reflect others. The color wavelength the object reflects is what we see as the object’s color. Oddly enough, “the color we perceive an object to be is precisely the color it isn’t: that is, the segment of the spectrum that is being reflected away.”3 So with that bit of confusing knowledge, let us move on.

The word red is derived “from Sanskrit rudhira [blood] and Proto-Germanic rauthaz.”4 In old English the term “reed” (red) described “the colour of blood, a ruby, a ripe tomato, etc.”5 The color red varies greatly in shade or hue and is sometimes described by a prefix noun or adjective, such as cherry-red, blood-red, or in the case of the fire service the term fire engine red.

Early red pigments used to make paint came from a variety of sources as time progressed. Some of these sources included mineral compounds, plant matter, and even the dried bodies of insects. Some of the early processes to produce some mineral pigments were toxic. Today’s paints are developed from mineral pigments providing the color and combined with a binder, solvent, and special additives depending on the type of application.

So when did people start using color to express themselves through art, customs, and their everyday life? A review of the historical beginnings of the use of color is in order. As to why exactly our early ancestors began the practice of coloring objects or drawing, we will leave to the extensive and scholarly discussions of the Paleoanthropologist or Archeologist.

Michel Pastoureau in his book Red, The History of a Color relates that Paleolithic people painted pictures on cave walls in Chauvet Cave (Ardèche, France) between 33,000 and 29,000 BCE.6 Besides using Charcoal for black line drawings, these people used red ocher or hematite (iron oxide mineral) mixed with various ingredients including animal fats to make various shades of red paint that could adhere to stone.7 Perhaps the first use of the color red. Pastoureau says that in ancient societies “red is the color of life” as exemplified by fire, “a source of light and heat.”8

Besides using color in paintings, early civilizations began to use color in clothing. According to St. Clair in the book The Secret Lives of Color, early civilizations “between the sixth and fourth millennia B.C.” first began the process of dyeing cloth.9 Red was one of the earliest colors to be used.

Egyptians were skilled at dying fabric and used Madder (a red pigment made from the root of the madder plant), and Kermes (a red pigment made from the Kermes insect). Other additives such as alum or lime were added to the mixture to allow the dye to “permeate the fibers of fabrics” and bond with them.10

In medieval times the color red was linked to Christianity and the Church through the symbolism related to the blood of Christ. Cardinals and even the Pope wore red and white garments or robes during religious ceremonies.11 The reader may recall from a previous article by the author in this series, The Maltese Cross, A Historical Symbol of the American Fire Service, that the Knights of St. John (that would become the Knights of Malta) wore a surcoat with “a white cross on a red ground – ‘The white Cross of Peace on a blood-red field or War’.”12 An institutionalized ritual during the Second Crusade was for knights to wear a small cross “cut from a piece of red cloth; it was always placed on the left shoulder of a tunic or cloak in memory of Christ bearing his cross.”13 Perhaps this laid the foundation for the later wearing of red by some armies (British Army “Red Coats” of the Revolutionary War) or the eventual adoption of wearing red shirts by early American firemen.

Eventually red became a popular and dominant color in the early American fire service, being used as a dye in early uniform shirts to identify firemen, and as a paint pigment to intensify the appearance of early fire “Enjines”. (A more in-depth discussion of this will be examined later in this chapter.)

Over time the color red not only became a chosen or preferred color to paint fire apparatus, but it also came to be used as a standardized color in fire training, fire prevention, and fire safety in the United States. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), a national fire consensus standard-making organization, established the NFPA 704, Standard System for the Identification of the Hazards of Materials for Emergency Response that uses a hazard diamond symbol to mark products to quickly relate the associated hazards in four categories: health, flammability, instability and specific hazards. The flammability quadrant of the diamond is always color-coded red for fire.14 The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) has also developed color-coded standards for industry that have been adopted by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to protect workers. The color red is used to identify “the location of fire protection equipment and apparatus such as fire alarm boxes, fire extinguishers, and industrial fire hydrants.”15

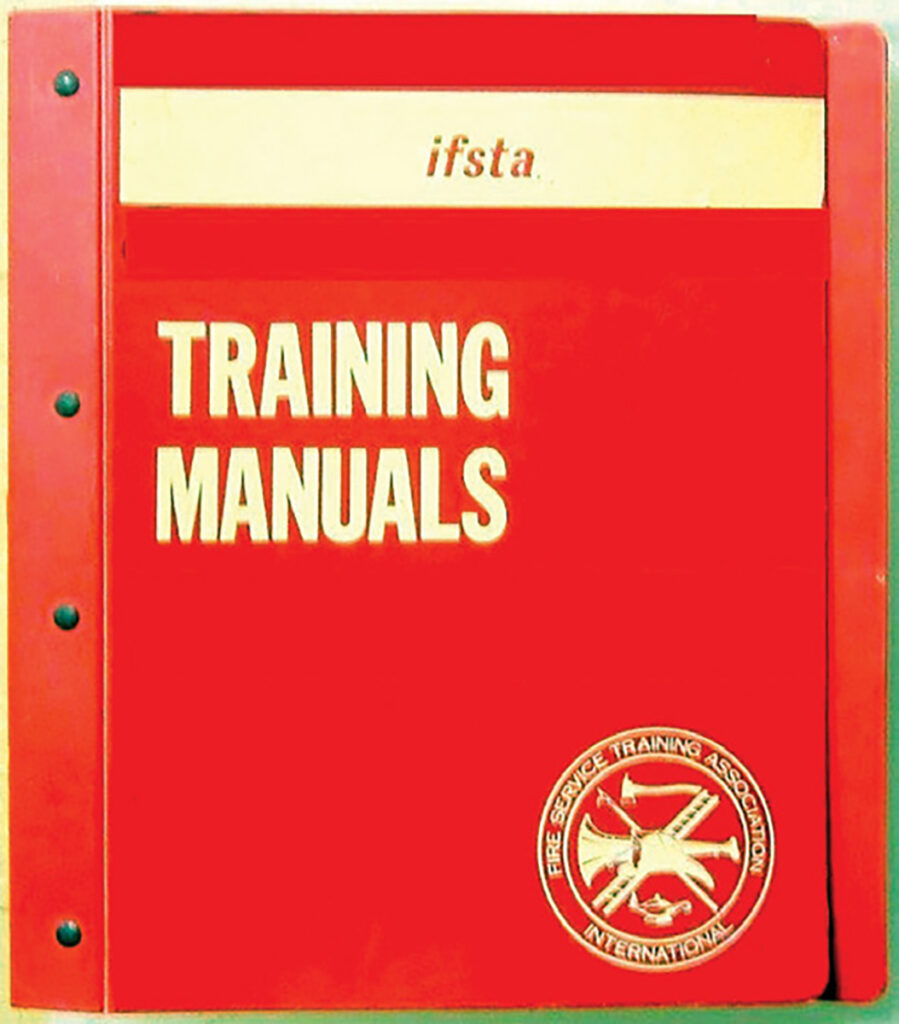

Red Books

In the early beginnings of fire service training, various groups utilized the color red as a cover binding to identify their training manuals. One of the most well-known of the early historic fire training manuals came from Oklahoma. Oklahoma A & M College (to become Oklahoma State University in 1957) “assumed the role of state fire training” in 1931.16 They began publishing an introductory fire training manual in 1934 that “later became the first ‘Redbook’ (noted by red covers).”17 Eventually the organization would become the International Fire Service Training Association in 1955.18 Vintage firefighters may recall full sets of these red-covered training manuals enclosed in red plastic binders in the fire station when they started their career or avocation in the fire service.

It should be mentioned that the color red has also had negative connotations associated with it throughout history, such as representing the devil and hades or being used to identify dangerous substances or situations. However, the use of the color red continues to be used today in a positive light to represent various organizations, causes, and fields of endeavor. The International Red Cross in its humanitarian mission uses a flag and emblem of a red cross on a white field. Also, red is a prominent color used on many national flags throughout the world including the United States flag. So too has the color red become a prominent part of the American fire service being used on emblems and emblazoned on fire apparatus. Now, let us delve into how this traditional use of red began in the American fire service.

The Beginning of a Tradition

As has been found in documenting other areas of fire service history, oral myths sometimes obscure the facts, and it is not always possible to discern the real history. However, there is some documented history of the use of red in the fire service that aids in authenticating its application and timeline.

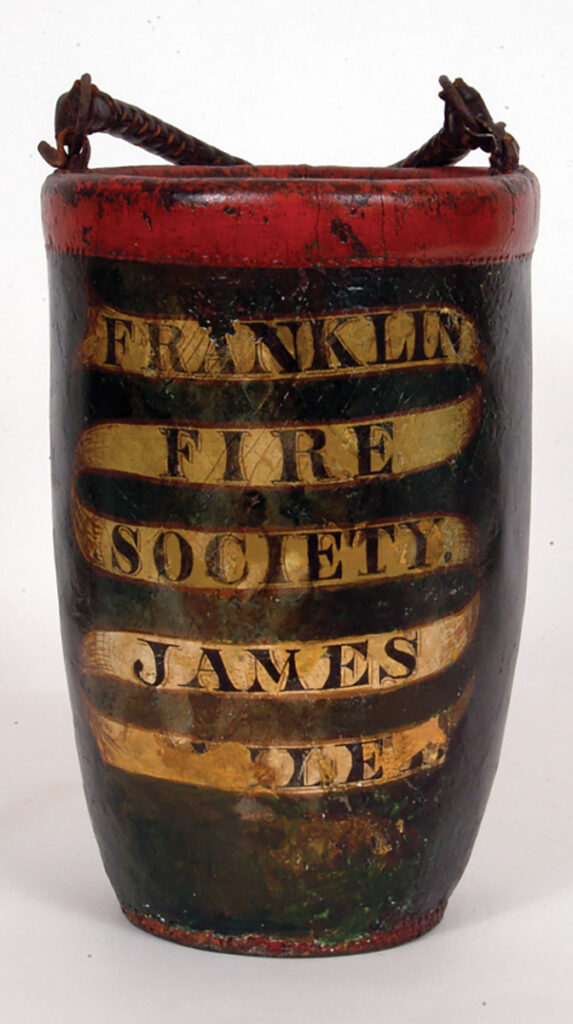

Perhaps the first use of the color red regarding fire protection was in the painting of fire buckets. In the early days of colonial America, a leather fire bucket was one of the first pieces of firefighting equipment utilized by citizens of the community to form bucket brigades when a fire broke out. Some of the first fire protection ordinances were passed during this time that required communities to be equipped with fire buckets in case of fire.19 Fire buckets were usually marked with some identifying marks so they could be claimed by the owner after the fire.

Individually owned fire buckets generally had the owner’s last name painted somewhere on the bucket to identify it. If residents were required to have more than one bucket then each bucket was also numbered. In some cases, fire buckets were highly decorated with a coat of arms, patriotic scenes, or a fire society’s emblem to help identify them. Organized Fire Societies were often well-recognized civic groups made up of the community’s leading citizens for fire protection. It was an honor to be selected as a member of these societies and therefore the members proudly displayed their membership through specially painted fire buckets. In some communities, leading citizens who were members of the fire society hired local artists to “personalize and decorate fire buckets.”20

In the early 1700’s the hand-pumped fire engine came into use and spread throughout the American colonies. Fire companies were formed by local citizens to man the engines and fight fire.21 As these fire companies developed into a significant firefighting force they began to stockpile and supply their buckets for providing a water supply to the pumper. Despite having a mechanical fire pump (“Enjine”) there was no pressurized water system to supply water to the pump and fire buckets were still used to fill the hand pumper. In some cases, the fire company’s buckets were painted in the same color scheme as the fire company’s hand-pumped engine and numbers.

We see historically the use of various colors, artwork, and/or names/numbers to decorate and identify fire buckets. There are examples of some fire company buckets being painted with red around the rim to help identify their buckets. It was difficult to see logos or numbers painted on the sides of the buckets when they were mixed in a pile with other buckets from the community after the fire, and thus the red rim.

So, what would come next, the red shirt or the red painted “enjine”?22 First we will examine the history of the firemen’s red shirt.

Red Shirts – A Desire to Belong

It should be mentioned that early colonial American towns/cities did not have a community-wide fire department. Fire protection was provided by individual groups organized into firefighting units. First formed as a fire society, they would later be called a fire company, such as an engine company or hose company. Though they would come together to fight the fire, they were managed as separate organizations, sometimes loosely structured under a community fire warden or the city officials. These individual fire companies had their own identity and loyalty to their company. However, a fire company was quick to adopt successful new ideas or customs from their fellow or rival fire companies. One of these new customs was for the wearing of a red shirt. The wearing of red shirts began during the era of the volunteer firemen and was a way to show membership and loyalty to their respective fire company.

The 1980 NFPA book Fire Terms included the term “red shirt”, and defined the term as “a volunteer fire fighter, derived from the bright red shirts once a part of the uniform.”23 Though the definition refers to volunteers, as historically documented further on in this section, the red shirt was also worn by some of the first career service firemen. This term was dropped from later editions of fire terms, perhaps because it was considered to be obsolete terminology. Unfortunately, historical terms like this have been deleted from fire service reference sources obscuring the history for future generations. However, the documented use of this term does illustrate that at one time the symbol of the red shirt had significant meaning in the fire service.

There is some disagreement among historians as to which fire company and period first adopted the practice of wearing red shirts as part of a uniform. According to fire historian John Morris in his book Fires and Firefighters, members of the “Honey Bee” Engine Co. 5 of New York were the first to wear “bright red shirts” but he did not reference exactly when this started.24 However, Holzman presented in his book The Romance of Firefighting, that the Protection Engine Company No. 5 of New York “adopted the red flannel shirt as their uniform in 1840.”25

Regarding the practice of wearing red shirts, Morris related that they “so suited the firefighters’ profession that it was quickly adopted by many other companies.”26 This red shirt soon became like a lodge or fraternity pin that identified the wearer as a member of the brotherhood of firefighters. Other companies also began the practice of wearing elaborate parade belts or “suspenders (usually red)” as part of their dress uniform.27

The red colored shirt, along with red suspenders, would quickly spread throughout the American fire service and establish one of the earliest traditions for firefighters.

As career fire departments began to be instituted, the tradition of the red shirt carried over to the full-time firefighters. The State of New York ordered the establishment of a Metropolitan Fire Department (MFD) for the City of New York toward the end of the Civil War. The rules and regulations of 1865 required the firemen to wear uniforms as follows: “Chief Engineer and other Engineer officers (chiefs) were instructed to wear a red flannel, double-breasted shirt, dark blue pilot cloth coat (knee length), vest and pantaloons of the same material, blue cloth cap and white fire hat.”28 In 1868, the “General Orders” changed the uniform requirements with chief officers wearing white shirts, while “red shirts then became part of the uniform for the company officers, with firemen and engineers of steamers continuing to wear blue shirts.”29

The Style of the Red Shirt

Volunteers might have different types of red shirts depending on the circumstances. They might wear a simple red “service” shirt for regular activities while wearing a “parade” shirt for parades and special occasions. The fancier “parade” shirt could be worn for fire response also. The service shirt was a standard style single-breasted shirt (single row of buttons on the front of shirt) made of wool flannel and long-sleeved. The “parade” shirt was generally a fancier style shirt with a double-breasted button front (two rows of buttons one to each side securing a bib front composed of a square or shield-shaped cloth front piece).30 The “parade” shirt is sometimes referred to today as a “cavalry” or “bib” style western shirt. Either the service or parade shirt could have regular pearl or cloth buttons. Special metal buttons with fire department (FD) stamped on them were available as an option from manufacturers. As more and more fire companies adopted the wearing of red, the custom of adorning the shirt front or bib with a cloth or embroidered number or letter initials of their fire company helped differentiate as to which company they were a member.

It was found in a period fire equipment sales catalog in New York from 1872, that a fireman plain shirt in either red or blue was $2.00 each, while a fireman “parade” shirt in either blue or red averaged $3.20 each.31 Bureau of Labor statistics for New York in 1872 showed a skilled worker wage of $1.75 per day.32 So volunteer firemen put in approximately two days of work at their job to purchase a “parade” shirt.

It should also be mentioned that the wearing of red shirts or the color red has had other meanings at different times in history, some linked to good intent and others to bad. Researchers will come across a number of these, two different examples of this follow. In recent years there has been a movement to support United States Military troops who are deployed abroad by wearing the color red on Friday. A positive display of support for our military who continue to serve and protect us in assignments overseas.33 A negative initiative from history is the Red Shirt Movement after the American Civil War regarding intimidation of African American voters by activists wearing red shirts.34

The Hand Fire Engine and Color

The American colonists faced the constant hazard of uncontrolled fire in their communities due to the use of combustible building materials, and open flame used for light, heating, and cooking. This along with the increase in incendiary fires and major conflagrations would lead the colonists to seek a better means of fighting fire besides the sole use of a fire bucket. The first fire pumps used in the American colonies were the “Newsham” hand-pumped fire engines from England. The first one was placed in service in Boston around 1678.35 Philadelphia and New York would follow Boston’s example and import Newsham engines in the early 1700’s.36 In 1743, New York City Council hired Thomas Lote, a cooper and boat builder, to build “an American engine that could compete with the British-made Newshams.”37 By the late 1700’s the American Colonies would see the beginning upstart of the American hand-engine manufacturing business, and the spread of hand-engines throughout the colonies. This would spawn the rise of volunteer engine companies.

The American colonist were proud of their freedoms and took civic duties to be a part of their service to support the community. The duty of the volunteer fireman was one of these well-respected civic duties that a citizen could perform. These newly formed fire companies soon became an independent powerful entity that “wielded considerable political influence by their numbers and strong organization.”38 As a strong independent group they would soon be the ones to make the decisions about the colors and trim that would adorn their “enjine.”

Early hand-engines were made primarily of wood. Their pump cylinders and brakes (pump levers) linkages and other fittings were made of metal, but the frame, wheels, water tub, and air chamber cover were all made of wood. Because these first “enjines” were mostly made of wood, the main surfaces had wood finishes sealed with protective coatings such as wood oils (linseed or tung oil), wax, or lacquer. These would be fairly cheap and readily available with wood artisans as part of their standard finishes. The brake arms or handles were made of oak “and were waxed and rubbed to a satin-smooth finish.”39 These finishes highlighted the natural beauty of the wood surfaces such as mahogany and oak used in the higher-quality apparatus.

The early Newsham and other hand-pumped fire engines had a tall upright air chamber that equalized the water flow coming from the two alternating pump cylinders, this gave a continuous flow instead of squirts of water. Coming off this was the discharge riser pipe which was mounted to a moveable water pipe/nozzle. This pipe and nozzle assembly was called a “goose-neck” because of its appearance. These “goose-neck” engines usually had a cabinet support structure built around the air chamber and riser. The “box” cabinet had removable side panels to allow access to service the engine components. According to Fire Historian Dunshee in his 1939 book, Enjine!-Enjine!, “the old goose-necks, with their high-backed panels, were more readily adaptable to decoration than any other type.”40 With this early design came the opportunity to carve intricate designs in the frame of the panels and have a beautiful oil painting featuring a portrait or landscape in the center. According to Dunshee celebrated artists of the time were hired to paint these panels. These paintings “often feature patriotic, heroic, or allegorical images to associate the volunteer companies with these lofty ideals.”41 To protect these elaborate works of art, the panels were usually removed “when the engines were hauled out for a fire,”42 During the period of the hand pump or handtub fire “Enjine”, the artistic paintings on some engine panels became more elaborate than the overall paint and ornamentation of the apparatus.

When an “enjine” was removed from service or sold it was common to remove the panels and hang them in the firehouse or present them to honored members of the engine company. This is one reason so many of these panel paintings remain today in museums and fire collections.

As time progressed and more engine companies were formed within a community, each company took pride in its engine and firefighting capability. They began to compete with each other both in firefighting and parades where they proudly displayed their engine. This would precipitate the elaborate painting, trim, and other ornamentation that would come to adorn the engines. According to Historian Morris, after testing a new engine, the fire company would establish a painting committee to decide on how to “dress her [the new engine] up.”43 This committee would decide on color, striping and other trim work.

It should be mentioned that the idea for quality painting, lines and stripes, and application of gold leaf decoration did not originate with fire companies. Opulent coach makers were already decorating the horse-drawn coaches of their wealthy clientele. However, these coaches were more modest in style than some of the lavishly adorned fire engines that were to come. From historical research, we find some family coaches and transportation company stagecoaches that were painted red.

So what color was used to first paint these hand-pumped engines? Historical records from the engine companies in New York, illustrate that some of the popular colors of the period were red, green, and black.44 David Falconi, a hand-engine historian, said that green was a popular color of hand engines in America up until about the 1850’s.45 New York’s Engine Company No. 3, painted their engine green after a memorable speech by one of their members, and after this “when No. 3 extinguished a fire it was said that she ‘painted it [the fire] green’.”46 This story and saying may have contributed to the early spread of the color green as an apparatus color in the colonial and early American fire service.

The era of the volunteer firemen and their hand engines certainly exemplified the desire to have the biggest and best, and the capacity to pump more water than other engine companies along with the finest-looking fire engine. Intricate paint lines and stripes with gold or silver colors, application of gold leaf designs, and silver plating of brass work could embellish a hand engine to be a real showpiece of apparatus, combining function with glittering art. As new apparatus was added to support the engine companies, such as hose companies with hose reels (jumpers) or hose wagons, they would receive a make-over as well. Some of these hose reels were “emblazoned all over with gold, silver, and the choicest artistic gems.”47 The phrase “all dressed up like a fire engine” was a “familiar American quotation” of the period.48

It should be mentioned that though the town aldermen or fire warden might authorize and provide payment for the purchase of a new engine, they were unwilling to pay for frivolous and expensive extras such as expensive paint, trim, and ornamentation. The firemen of the fire company would be responsible for providing for the cost of painting and other trim. They did this through personal or community donations or other fundraising venues. This early tradition of the firemen paying for the painting of the engine may have contributed to the oral myth that firemen selected the most expensive paint color for their engine (in the oral myth – red).

So how did the firemen finally get around to creating the tradition of red fire apparatus?

Pigment, Painting, and Cost

As was mentioned earlier in this chapter, some type of pigment is used for colorization to make paint. According to academic research done on historic paint processes of the period, paints were composed of “three components: (1) pigment, to make the paint opaque and to add color; (2) a binder (such as oil, chalk for water-based paints, hide glue, or gelatin) to bind the pigment particles together; (3) and, a vehicle (or medium), which is the fluid component of paint (such as turpentine in oil paints, or water in water-based paints).”49

The paint was hand-made by local artisans in small batches up until the late 1800s when the demand for paint made large-scale ready-mix paint profitable. However, this factory-manufactured paint was not readily available throughout the country.50 The first commercial paints were sold as pigment dissolved in oil with varnish added by the painter when they were ready to paint.51 Not until the development of the automobile and the motorized fire apparatus did pre-manufactured paint come into general use in the fire apparatus industry. During this time synthetic paints, new coatings, additives, and processes began to be developed.

From the days of the fire bucket up to the age of steam, fire apparatus paints were hand-made by artisans. Pigments were ground at first by hand and then with the use of mechanical grinders to make a fine powder to mix with a binder and medium to make paint. These paints had limited “pot” life so they were mixed in small batches and used that day. With inconsistencies in pigment, mixing, and application, it would have been difficult in the early days to routinely produce a matching paint color from one batch to another.

As a related side note, in the 1800’s it became popular to paint barns to help preserve the bare wood longer. A common color that penetrated well into boards and resisted fading was Venetian red. This paint was made from clay containing iron oxide found first in Italy and later dug in Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Virginia where it was called Indian red. As an earth pigment and acquired locally, it was relatively inexpensive, thus being used as barn paint. The 1922 Sears catalog listed it for about half the cost of other house paints.52

Vermillion red was a preferred red pigment that came to be used for fire apparatus, with American Vermillion being cheaper coming from local resources. Based on ledger or journal entries from the 1860s, English Vermillion a finer, purer pigment was $1.25 per pound and used sometimes for painting fine lines or details. American Vermillion cost was $0.50 per pound.53 Though it wasn’t cheap it wasn’t as expensive as some other pigments. The previously mentioned barn paint, Indian red was less than half the cost of American Vermillion. Regarding the oral myths that red was used because it was the most expensive pigment/paint, or the reverse myth that it was the cheapest, it appears that neither of them stands out as the most apt reason. Though pigment cost was a factor in paint costs, there were other factors to consider. The cost of the other ingredients, along with the painting process including the number of primer and finish coats, all factored into the cost of painting the fire apparatus of the period. Slapping one coat of Indian red on a barn was not the same as the quality painting of the cherished fire apparatus. If firemen had simply chosen a color based on cost, they could have gone with ultramarine blue one of the most expensive pigments per pound.54 There was at least one engine company that painted their engine blue. Called the “Blue Box”, a piano box style hand-engine of 1803, it was manned by the “Blue Boys” of Jefferson Engine 26 of New York.55

A clear varnish was used as a final protective coating on the painted engine. However, over time the varnish would darken and make the paint appear less bright. Also, due to sunlight fading and chemical changes over time, along with successive layers of re-painting, make it difficult to determine the original color of the paint used in the past.56 However, new techniques using microscopic analysis to determine paint components have helped to determine a more accurate true color of historic paints.

Historic Paint and Embellishment Process of Fire Apparatus

In this section, we will cover a general description and explanation of the historic painting and embellishment process for fire apparatus. Depending on the fire apparatus manufacturer and the specific time, the process may have varied. The author highly appreciates and acknowledges the information and tutelage provided by Peter Achorn in the following narrative. Peter Achorn is a master artisan in the painting and embellishment of historic fire apparatus including painting, pinstriping, gilding, and decal application. He began his career as an apprentice sign painter and over time acquired and mastered the many skills of his craft. For over thirty years he has worked on the restoration of antique fire apparatus paint and decoration. His artisan skills and historical research have provided him with a unique and knowledgeable perspective on the painting and embellishment of historic fire apparatus.

As was previously covered, early hand engines were generally painted and decorated by local artisans hired by the fire company after the delivery of the apparatus. Late in the period of the hand engines manufacturers began offering the option for custom painting and embellishment of the fire engine before it was delivered.57 With the coming of the factory-made steam fire engine in the mid-1800s, the painting and embellishment of the engine became a part of the factory assembly process.

The embellishment of a fire engine refers to the added final decoration of the apparatus that may include hand lettering, line and stripes (pinstriping), gilding (gold leaf) scroll-work, and application of decals. A skilled painter that had mastered the art of lettering and line and striping was called a “fancy painter”. The term pin striping was not used until around the early 1900’s. Before it was called line and stripe. A painted line larger than ¼” in width was called a stripe, and a line smaller than ¼” in width was a line. Artisans specializing in painted scroll-work or decals were called an ornamentor. Scroll-work is a general term used to describe the fancy corner details, such as intricate designs or flowers (Fleur-de-lis), at the corners where two stripes or lines meet.58

The various steam fire engine manufacturers employed skilled artisans for the painting and embellishment process of finishing the apparatus at the factory. These artisan painters had learned their trade through apprenticeship work in carriage or sign shops. The master artisans (fancy painters) would be assisted by apprentices who were learning the trade. The apprentice would come in early and grind the pigment for the paint that would be used that day. Pigments such as Vermillion would change color from cherry-red to orange-red depending on the length of time it was ground. The painter would mix the paint depending on the application step. Painting was a multi-step process. A primer or base coat was first applied. During the period, several coats of paint would need to be applied to get the full coverage and desired color. Paint would be allowed to dry for a day to several days between coats. In the case of red paint, the cheaper vermillion might be used for initial paint coats with more expensive carmine red used toward the end for a deeper red color.59

Before the final coats of clear varnish were applied to protect the paint, the fancy painters would hand paint lettering, along with line and stripe the apparatus. Painted or decal application of corner scroll work would also be applied at this stage. After these final embellishments, the paint and ornamentations would be sealed by final coats of clear varnish. Varnish of the period would have been made of tree sap selected for clarity and ability to dry to a hard durable finish.60

As can be seen, the painting and embellishment of fire apparatus in the mid-1800s to early 1900s was a time-consuming process. However, the assembly process and painting of several apparatus at the same time made it more efficient and economized cost. This encouraged manufacturers to standardize on a specific color of paint and style of embellishment. Though a manufacturer might standardize a design for striping and scroll work, each artisan added their unique style to the process.

The Steamer to Motorized Apparatus

As the age of steam entered the fire service (the mid-1800s), the “steamer” fire engines did not have the flat spaces for elaborate paintings like the pump boxes of the old handtubs. Manufacturers used the finished metal parts such as copper or brass to put a highly polished shine to the steamers. Cast iron parts like the boiler were generally painted black, while iron or steel frame components were usually painted red. These frame members and the wagon wheels soon became a place for additional adornment with detailed pin striping or gold leaf application. As the fire apparatus manufacturers expanded to meet demand, they added personnel including full-time painters and gold leaf artisans. As explained previously, this changed the process from the painting of fire apparatus after delivery by local artisans to factory painting and custom work to meet client specifications. With the steamer’s factory assembly and painting approach, the color red became a standard color for fire apparatus.61 Red was a good bright contrast color to the large black boiler and other polished metal components.

The hose wagon that carried the fire hose would have the exterior painted in the fire department’s colors except for the hose bed. The area where the hose was stored would have a natural wood shellac or varnish finish. This would be to keep paint from rubbing off on the fire hose itself as it was loaded or unloaded from the wagon bed. Generally, the “drive pole” or wagon tongue had a natural wood finish with forged metal brackets painted black or silver.

Unfortunately, the romantic age of strong galloping horses pulling the polished, smoking steamer would only last about 65 years. First to go were the horses when they were replaced by the invention of the internal combustion engine to haul the steamer. Ultimately the internal combustion engine would power both the drive gear and the pump.

By the 1920s, motorized fire apparatus would become the new standard for fire response and extinguishment. With the new automotive era came metal-enclosed vehicle bodies, curved fenders, and fine detail that provided new areas on the fire apparatus that could be painted and decorated. Soon new painting techniques and continuing refinements in pin striping, along with chrome-plated accessories would take the appearance of the working fire apparatus to new heights of splendor. As fire apparatus manufacturers shifted from steamers to motorized vehicles, the popular red color already in use continued to be the standard for fire apparatus.

Based on this review of the color red related to the fire service, it leads one to surmise that it wasn’t cost or the color competition with other vehicles that affected the firemen’s choice of the color red. Empirical data seems to indicate that the bright appearance and historic symbolism created the attraction that led our fire service predecessors to choose red as a dominant color for the fire service.

Visibility and Conspicuity of Fire Apparatus

In the last sixty years many studies have been conducted identifying the best color, reflectivity, and lighting for emergency service vehicles, and in particular fire apparatus. In this article, we have focused on the history of the color red as it has spanned multiple centuries of the American fire service. However, the research and controversy of recent years attempting to make fire apparatus safer based on color needs to be briefly examined.

Perhaps the first major study regarding changing the actual color of fire apparatus was conducted in England in 1965. Lanchester College of Technology and Coventry Fire Brigade’s joint study “concluded that the color lime or bright yellow was actually easier to see in a variation of lighting — including at night.”62 The findings of this study crossed the big pond and the U.S. Fire Service began seeing some departments switching to yellow or lime-green fire apparatus in the 1970’s. In the 1990s, Optometrist Stephen S. Solomon began promoting lime-yellow fire apparatus over red based on accident comparison data. A later four-year study by Solomon and James G. King printed in the Journal of Safety Research, “found that the risk of visibility-related, multiple vehicle accidents may be as much as three times greater for red or red/white fire trucks compared to lime-yellow/white trucks.”63

However, in a 2009 study conducted by the U.S. Fire Administration it was “concluded that the paint color was not important.”64 Regarding emergency apparatus color, the report stated that: “Whatever the specific color, research performed for this report suggests what is more important is the ability for drivers to recognize the vehicle for what it is. (Schmidt-Clausen, 2000)”65 In addition, it is “theoretically possible to ‘overdo’” when it comes to reflective striping and colored lights.66 The researchers found that the driving public needs to be able to perceive that the vehicle is an emergency vehicle. This perhaps leads one to make the assumption that people recognize fire apparatus based on the color and appearance of the fire apparatus where they grew up. The study recommended a combination of color, reflective stripping, emergency lights, and other identity factors to increase visibility and safety.

The National Fire Protection Association has for years provided consensus standards to guide the fire service in best practices. In the past NFPA 1901, Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus provided recommendations on apparatus design including colors, striping, and lighting. It is being replaced by a compilation standard in 2024 covering all fire response vehicles, NFPA 1900 Standard for Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting Vehicles, Automotive Fire Apparatus, Wildland Fire Apparatus, and Automotive Ambulances. This standard relies more on retroreflective striping and lighting than color to make fire apparatus safer in responding and on the emergency scene.

So, though fire apparatus can still be red or almost any other color, reflective striping and light combinations as promulgated by recommended standards affect the appearance of today’s fire apparatus. Unfortunately, these requirements seem to have visually obscured the beautiful and artistic gold, silver, or matching color pinstripe, scroll-work, and/or decorative fleur-de-lis of the past heyday of early motorized apparatus.

Today’s Fire Apparatus Color and Graphics

So how has the paint color and process changed on fire apparatus today? The composition of paints and the painting process began to change in the 1960s and today there are more durable primers and paints available in a multitude of colors. Fire apparatus manufacturers now use a multistep paint and finishing process, along with computer graphics and modern vinyls to produce customized fire apparatus finishes and graphics packages that meet the specifications of almost any customer. In general, each apparatus manufacturer has their proprietary paint colors, but they can match existing fleet colors for the fire department customer.

Gold leaf lettering and hand-painted striping are still available from a few remaining artisans. However, almost all the manufacturers now use gold on vinyl or a SignGold vinyl using computer graphics programs and plotters to produce and cut out lettering and designs. The new vinyl processes are more durable and have a longer life compared to real gold leaf which requires maintenance and clear coating over time. Vinyl is also used for pin striping these days and looks like it is hand-painted. Though gold and silver pen stripes are favorites, in recent years black reflective striping has gained in popularity. Fire department emblems are made as full-color decals and applied then clear coated.

So what is the most requested color on fire apparatus today? Red is still popular but now being used in two-color paint schemes such as red and white or red and black. Regarding the color red, there is no standard red in the fire service. The color varies in shade depending on the manufacturer or the fire department’s preferences. Some departments like a brighter red such as a candy-apple red, while others lean toward a darker cherry red.

Scott Shelton, owner of Fire Master Fire Equipment, Inc., said that red is a dominant color with about 95% of the apparatus they manufacture being red.67 However, he related that split colors have become popular such as black or white over red. Scott related that one of the unique colors they have done was a solid blue fire apparatus for a refinery. Brad Johnston, President of Precision Fire Apparatus, said that about 50% of the apparatus they sell is red but of those most are a two-tone combination with charcoal over red becoming a popular color combination.68 They are also seeing requests for matching local school or city colors. Brad related that a memorable recent color design was white over chartreuse. Columbia (MO) Fire Department, which serves the City of Columbia and the University of Missouri’s main campus, purchased an Air Supply Truck in 2009 during Chief William Markgraf’s tenure that was painted in the University’s colors, black and gold.

The Legacy of Traditions and Change

This chapter examined the question of why red is such a predominant part of the American fire service, and through this review finds a historical explanation for this tradition. A tradition that has forever linked the color red to the fire service as illustrated by its use on fire apparatus and other firefighting paraphernalia across many centuries.

Paleoanthropologists have identified cave paintings that show the color red held a prominent place in the life of early man. The human fascination with the color and symbolism of red has been expressed throughout history. Seen in art and form the color has been embraced by groups, alliances, and religious ceremonies. So too has the color red become a symbolic part of the American fire service. Beginning with a desire to belong to a noble volunteer group, the early firemen donned a distinctive red colored shirt to show their membership in the elite public service organization of its time. The color red was also used to highlight their prized firefighting equipment, the fire bucket and then the venerated hand-pumped “Enjine”. With the advancements in fire fighting pumps and equipment, such as the iconic steamer, the color red became more entrenched in the traditions of the fire service. By the time of the internal combustion engine and the motorization of the fire service, red was a predominant color for fire apparatus.

This review of the color red related to the fire service leads one to surmise that it wasn’t the cost of the paint or the competition with other vehicles that affected the firemen’s choice of the color red. Empirical data seems to indicate that the bright appearance and historic symbolism created the attraction that led our fire service predecessors to choose red as a dominant color for the fire service.

Today, according to the Fire Apparatus Manufacturing Association (FAMA), “Fire Engine Red” remains the most popular choice of paint color, and “has been used on thousands of fire apparatus over the years.”69

Though new standards have instituted safety requirements related to reflective striping and graphics, today’s fire apparatus still replicates the colors and embellishments that trace their origins to the early beginnings of the American fire service.

The color of your fire department’s apparatus may or may not be red, but there is a history as to why and what the color represents to the current and passed firefighters of your department and your community. For too long oral myths have been concocted, embellished, and passed on as hyperbole to ultimately become accepted as truth while displacing the real history and traditions of the fire service. I encourage you to do your own research and learn the true history and traditions of your fire department or organization, and thereby understand how it influences the current and future fire protection of your community. What you learn and pass on to others may one day be an important footnote in the continuing history and traditions that shape the American fire service.

Authors Comments

The author wishes to recognize and thank the fire service personnel and organizations for their assistance in the development of this article. In particular, the author expresses his appreciation to:

Curtis Peters, Board Chair Vintage Fire Museum, Jeffersonville, IN; David Falconi, Founder/Owner Handtub Junction, USA, Southborough, MA; Chief (Ret.) Darryl Kerley, Oak Ridge FD and Seymour VFD, TN; Assistant Chief Jerry Jenkins, Columbia (MO) Fire Department; Peter Achorn, Master Artisan and Owner of Fire Gold, South Thomaston, ME; and the University of Missouri Ellis Library/Lending Library for assisting the author in obtaining the inter-library loan of various research documents and archival materials.

The author also wishes to recognize all the various Historians, Authors, and Artisans for their extensive and invaluable work in preserving Fire Service History through artifact notes, articles, books, and websites that have been used for research purposes by the author and footnoted in this series. May their work continue to endure the ages and preserve the true history and traditions of the American Fire Service.

The A Part of Fire Service History series of articles are copyrighted © 2023-2024 by the author and are published under permission granted to the FFAM.

Endnotes

- The Model T, “The Model T is Ford’s Universal Car That Put the World on Wheels”, Ford Motor Company, 2020, web article accessed January 3, 2024, https://corporate.ford.com/articles/history/the-model-t.html.

- Tanya Kelley, “red.” Encyclopedia Britannica, December 15, 2023, webpage accessed Dec, 27, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/science/red-color.

- Kassia St. Clair, The Secret Lives of Color, Penguin Books, New York, NY, 2017, p. 13.)

- Tanya Kelley, “red.” Encyclopedia Britannica, December 15, 2023, webpage accessed Dec, 27, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/science/red-color.

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “red (adj. & n.),” December 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1089329307.

- Michel Pastoureau, Red, The History of a Color, (Translated from the French by Judy Gladding), Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2017, p. 16-17.

- Ibid, p. 18.

- Ibid, p. 23.

- Kassia St. Clair, The Secret Lives of Color, p. 135.

- Michel Pastoureau, Red, The History of a Color, p. 37.

- Ibid, p. 69.

- Ernle Bradford, The Shield and The Sword, Open Road Integrated Media, New York, 2014, p. 16.

- Pastoureau, Red, The History of a Color, p. 68.

- Jonathan Hart, “Hazardous Materials Identification”, National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), November 5, 2021, web article accessed January 12, 2024: https://www.nfpa.org/news-blogs-and-articles/blogs/2021/11/05/hazardous-materials-identification .

- David W. Smith, Extension Safety Program, “The Color of Safety”, AgriLife Extension, Texas A&M System, agsafety.tamu.edu.

- “IFSTA History”, International Fire Service Training Association, Oklahoma State University, 2024, web article accessed Jan 15, 2024, http://ifsta.org/about-us/history .

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Herbert Theodore Jenness, Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present, Cambridge, Mass, 1909, p 2.

- Jackson Landers, “In the Early 19th Century, Firefighters Fought Fires … and Each Other”, Smithsonian Magazine, September 27, 2016, web article accessed January 4, 2024, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/early-19-century-firefighters-fought-fires-each-other-180960391/.

- For more information of the history of hand pumped fire engines, see: “Handtubs and Hand Pumped Fire Engines, A Part of Fire Service History”, FFAM Magazine, November/December 2023, Vol. 66, Issue 6, p 8–10, 12, 36-45.

- The word “Enjine” is an archaic term that was used in relation to a hand-pumped fire engine during Colonial and early American period of the United States. It was pronounced as spelled, being a term of affection and veneration for the fire engine by the engine company’s firemen.

- Ralph W. Burklin, and Robert G. Purington, “Red Shirt”, National Fire Protection Association’s (NFPA) Fire Terms, A Guide To Their Meaning and Use, NFPA, Boston, MA, 1980, p. 152.

- John V. Morris, Fires and Firefighters, Bramhall House: New York, 1955, p. 63.

- Robert S. Holzman, The Romance of Firefighting, Bonanza Books/Crown Publishers, Inc., New York,1956, p. 37-38.

- John V. Morris, Fires and Firefighters, p. 63.

- Robert S. Holzman, The Romance of Firefighting, p. 38.

- Janet Kimmerly, Editor, Fire Department City of New York, The Bravest, an Illustrated History 1865 to 2002, History from 1865 – 1999 written by Paul Hashagen, Turner Publishing Company, Paducah, KY, 2002, p. 52.

- Ibid.

- Cairns & Brothers, Firemen’s Equipment, Catalog Number 27, New York, p. 29.

- Prices averaged per shirt by author, based on pricing structure related to “Shirts” in: Fred J. Miller’s, Illustrated Catalogue of Fire Apparatus, and Fire Department Supplies (Reprint), Brooklyn, New York, 1872, p. 30.

- History of Wages in the United States From Colonial Times to 1928 : Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, No. 604, 1929, retrieved through Fraser, Discover Economic History/Federal Reserve, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/history-wages-united-states-colonial-times-1928-4126?start_page=185 , p. 175.

- Eric Milzarski, “This Is How ‘RED Friday’ Became a Thing and Why It Still Matters Today”, We Are The Mighty, Military.com, October 22, 2018, https://www.military.com/undertheradar/2018/10/22/how-red-friday-became-thing-and-why-it-still-matters-today.html .

- “Red Shirts”, Dictionary of American History. Encyclopedia.com. (January 8, 2024). https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/red-shirts.

- Herbert Theodore Jenness, Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present, p 100.

- David Hedrick, “Handtubs and Hand Pumped Fire Engines, A Part of Fire Service History”, FFAM Magazine, Fire Fighters Association of Missouri, Warrensburg, MO, November/December 2023, Vol. 66, Issue 6, p 12.

- Dennis Smith, Dennis Smith’s History of Firefighting in America, 300 Years of Courage, The Dial Press, New York, 1976, p. 16.

- Kenneth Holcomb Dunshee, Enjine! – Enjine!, A story of Fire Protection, published by Harold Vincent Smith, The Home Insurance Company, New York, 1939, p. 45.

- Endnote: John V. Morris, Fires and Firefighters, p. 106.

- Kenneth Holcomb Dunshee, Enjine! – Enjine!, A story of Fire Protection, published by Harold Vincent Smith, The Home Insurance Company, New York, 1939, p. 59.

- “Eagle on Top of Globe” Engine Panel Painting (description), Smithsonian Institute, National Museum of American History, accessed Jan. 25, 2024, https://www.si.edu/object/eagle-top-globe-engine-panel-painting:nmah_1341236 .

- Dunshee, Enjine! – Enjine!, p. 60.

- Morris, Fires and Firefighters, p. 104.

- Dunshee, Enjine! – Enjine!, p. 12.

- From telephone interview with David Falconi, Handtub restorer and Founder of Handtub Junction, USA, by author on September 28, 2023.

- Dunshee, Enjine! – Enjine!, p. 57.

- Ibid, p. 60.

- John V. Morris, Fires and Firefighters, p. 59.

- Jessica Parker Dockerya, Pre-1850 Paint in Historic Properties: Treatment Options and Processes, Graduate Thesis The University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 2005, p. 4.

- “History of Paint”, American Coatings Association, Washington, DC, 2024, web page accessed Jan. 24, 2024, https://www.paint.org/about/industry/history/ .

- From telephone interview with Peter Achorn, master artisan in the painting and embellishment of historic fire apparatus, (Fire Gold) South Thomaston, ME, by author on February 21, 2024.

- Thomas Durant Visser, “Why are barns painted red?”, Morning AgClips, University of Vermont, November 23, 2021, web article accessed Jan. 25, 2024, https://www.morningagclips.com/why-are-barns-painted-red/.

- Peter Achorn, “Pigments and Color”, Fire Gold, Tenants Harbor, ME, 1999 – 2019 (current South Thomaston, ME), web page accessed Dec. 14, 2023, http://www.firegold.com/pigment.html.

- Ibid.

- Dunshee, Enjine! – Enjine!, p. 21.

- 56 Robert Foley, Paint in the 18th – Century Newport, Newport Restoration Foundation, 2009, p. 3.

- David Falconi, The Encyclopedia of American Hand Fire Engines, Handtub Junction USA, Southborough, MA, 2001, p. 13.

- From telephone interview with Peter Achorn, master artisan in the painting and embellishment of historic fire apparatus, (Fire Gold) South Thomaston, ME, by author on February 21, 2024.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sarah Calams, “Why are fire trucks red?”, FireRescue1, Lexipol Media Group, Jan. 13, 2017, 2024, web article accessed Jan. 15, 2024, https://www.firerescue1.com/fire-products/fire-apparatus/articles/why-are-fire-trucks-red-hTQgOBUIOZzjc4QC/ .

- “Why lime-yellow fire trucks are safer than red”, American Psychological Association, 2017, web article accessed Jan. 15, 2024, https://www.apa.org/topics/safety-design/fire-engine-color-safety#:~:text=Solomon%2C%20OD%2C%20an%20optometrist%2C,vehicles%20with%20white%20upper%20cabs.

- Sarah Calams, “Why are fire trucks red?”, FireRescue1,

- Emergency Vehicle Visibility and Conspicuity Study, FA-323/August 2009, United States Fire Administration, U.S. Department of Homeland Security/FEMA, Emmitsburg, Maryland, 2009, p. 21.

- Ibid, p. 22.

- From telephone interview with Scott Shelton, Owner of Fire Master Fire Equipment, Inc., Springfield, MO, by author on January 18, 2024.

- From telephone interview with Brad Johnston, President of Precision Fire Apparatus, Camdenton, MO, by author on January 18, 2024.

- Fire Apparatus Manufacturers’ Association (FAMA), “Fire Apparatus Color and Graphic Trends”, Ocala, FL, 2024, webpage accessed January 4, 2024, https://www.fama.org/forum_articles/fire-apparatus-color-and-graphics-trends/.