A Part of Fire Service History

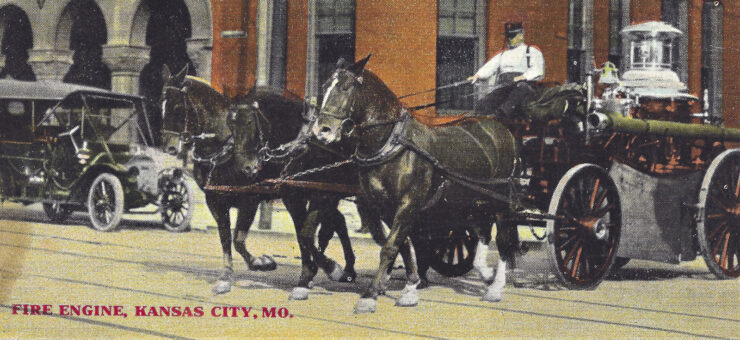

When one thinks about the history and traditions of the fire service, a unique picture that comes to mind is the image of an old-time steam fire engine belching steam and being pulled by a galloping team of horses responding to a fire alarm. Even though this traditional response occurred before the current generations’ memories, history books, movies, video clips on the internet, and even re-enactments have made this an iconic image of the historic fire service. The awe-inspiring picturesque age of firefighting, brave souls devoted to their heroic task, using the latest technology of the day to save lives and property. The strong horses at full gallop pulling the heavy, brightly polished steamer down a cobblestone street at breakneck speed as kids and other citizens rush to follow in its wake and witness the excitement and heroism of a firefighting operation in their hometown.

In previous articles in this series on fire service history, we have covered several developments including fire station design, fire poles, and the addition of horses to pull early fire apparatus. In these articles, it can be seen that the common factor in the development of these features, components, and procedures was driven by a new type of fire engine being introduced in the fire service, the steam-powered fire pump. In past segments, we have skirted around this historical new development and the significant change it brought to the fire service. In this article, we will take a more detailed examination of the development of steam fire engines and the changes and traditions that they brought about in the fire service. We will also review some of the early adopters of steam-fired apparatus in Missouri.

The Coming Age of Steam

First, it would be helpful to define what a “steam engine” is before we discuss its application to firefighting as a “fire engine.” The Encyclopedia Britannica defines a “steam engine” as a “machine using steam power to perform mechanical work through the agency of heat.”1 In other words, the steam engine is a means by which a heat source, usually a boiler, converts water to steam, and the resulting energy of the expanding steam is used in an engine to create a motive power source. Now let us examine the early theory and developments of steam power.

As has been presented in previous articles in this fire history series, the period of the Industrial Revolution, the mid-1700s to 1800s, was a time when “technological changes introduced novel ways of working and living and fundamentally transformed society.”2 The development of these new technologies led to new ways of applying them to address old problems and improve life and safety. The invention of a steam-powered fire-pumping engine came about as part of this Industrial Revolution. The foundational idea for the development of a steam fire engine stretches back to the time of the first century. Heron of Alexandria, Egypt, a Greek mathematician, was also an inventor and created “the aeolipile, the first steam-powered engine.” The device was constructed of a “sphere mounted on a boiler by an axial shaft with two canted nozzles that produce a rotary motion” using escaping steam.3 At the time, the device was considered an impractical toy.

Based on research in the history of steam power, “the first commercially successful steam engine” (steam power application not related to firefighting), is credited to Thomas Newcomen, for building “his first machine near Dudley Castle in Staffordshire in 1712.”4 There was little advancement in the Newcomen atmospheric engine until the work of James Watt developed and patented new technology in 1769. After that many people contributed to the continuing “improvements for more than a century.”5

Steam-powered engines were a key source of power driving the Industrial Revolution. This power source ran various machines to produce goods and services for the growing population. The first successful practical use of steam power for a steam railway locomotive was invented by John Blenkinsop in 1812.6 These early uses of steam power applied to industry formed the basis for the invention of the steam fire engine.

Setting the Stage for Change in the Early American Fire service

A change from bucket brigades to hand-pumped fire engines in the mid-1700s brought a change in fire protection for early America. The hand engines, powered by manpower working the pump levers (brakes) could now generate fire streams that were more efficient than tossing water from buckets. However, these hand engines left much to be desired. They generally took large numbers of volunteers to work the brakes and at a pump stroke of once a second, these men quickly tired out. As the industrial age caused people to move from farm to city to work in industry, cities grew large and cramped with houses and factories built of readily available wood that was combustible. Fires and the potential for resulting community-wide conflagrations were constant hazards. Also, in this industrial age, there was a shift in the type of volunteers who manned the local fire department. In early colonial days “volunteer fire companies were the pillars of their communities,” including prominent businessmen and leading citizens.7 There was a sense of pride and desire to serve beyond one’s self for the public good. As firehouses in urban areas grew into social clubs, some of the “volunteer firefighting organizations deteriorated to the point where they were comprised mainly of lower class citizens – rowdies, brawlers, drunks, and troublemakers.”8

Though many volunteer fire departments took their job seriously, some saw fires as a way to compete with rival fire companies. Even to the point of brawling over who got to the plug (hydrant/water supply) first or had the first line (or water) on the fire. While they fought the fire continued unchecked.

These and other factors would come together to drive the leadership of some metropolitan communities and insurance agents to seek a better more efficient method of firefighting. The stage was set for another major change in the fire service, and steam power would be one of the instruments that would drive this change. However, this change would not come easily. There were several volunteer firemen who “felt that human brawn was more effective, and certainly more romantic, than a machine that did all the work.”9

The circumstances described in the preceding paragraphs are not to be taken as representative of the entire fire service at the time. There were still dependable and capable volunteers protecting other communities, and fire departments that willingly supported the adoption of new technology such as steam fire engines. They too are part of this historical period in the fire service, but not as prominent in propelling the change.

England’s Development of the Steam Fire Engine

Credit for the first steam fire engine goes to George Braithwaite, a hydraulic engineer, assisted by Captain John Ericsson, inventor, in 1829. The steam engine was named “Novelty” and was built in London, England.10 The engine raised ten horsepower and weighed two and a quarter tons. It could “throw 200 to 250 gallons of water per minute to the height of 90 feet.”11 Though it responded to many fires in London and demonstrated its great value in fighting a fire, it was not accepted by the fire service or the public. At the time the people of London “would have none of the new-fangled machines and stuck to their hand-tubs, of which they use a great many at the present day.”12

Braithwaite was able to convince other countries of the capability of his machine and built several more steam-fire engines. Among those interested in his invention was the King of Prussia who bought an engine in 1832 to protect Berlin from fire.13 Discouraged by a lack of further success, Braithwaite discontinued his invention. It would be several years later that Americans took on the challenge of building and adopting steam fire engines as a recognized method of fighting a fire.

First American Steam Fire Engines

In the winter of 1839-40 in New York City, there was an alarming number of extensive fires that occurred. Because of this, insurance companies were pressing for a more efficient method of fighting fire than the hand-operated fire pumps. Insurance underwriters and the insurance companies commissioned Paul R. Hodge, a local mechanical engineer, to build a steam fire engine. The specifications were pretty general, basically that it should “throw a stream of water over the flag-staff of the city hall.”14 The engine was completed in the spring of 1841. It was self-propelled and extremely heavy weighing between seven and eight tons. It did meet the requirements by throwing a 1½ in. stream over the flagstaff of city hall. Though it was approved by the insurance companies, they could not get a fire company to agree to operate the engine. The firefighters were greatly opposed to using steam fire engines, fearing it would make hand engines of “no account” and supplant their position and political prominence as firemen for the city. And perhaps the biggest issue, just like today, is the fear of change. Finally the Pearl Hose Company, No. 28 agreed to man the steamer and therefore became the first fire company to use a steam fire engine in America.15 However, after several months because of complaints about its weight and ability to produce steam, as well as its continuing unpopularity it was removed from service and sold for use as a steam power source in a manufacturing plant.

Here we should at least mention again the name of Captain John Ericsson. He had helped Braithwaite build his first engine in London. He moved to America in 1839. In 1840 the New York Mechanics’ Institute offered “a gold medal for the best design for a steam fire engine.”16 Ericsson won the prize for his design. The design reduced the weight to less than two and a half tons, and could “throw 3,000 lbs. of water per minute to a height of 105 ft., through a 1½ inch nozzle.”17 Though this engine was never built, it proved that there could be a workable design for a practical steam fire engine. As another historical point, Ericsson is best remembered as the designer of the iron-clad marine vessel the Monitor during the American Civil War.

At this point, we need to cover a little more in the development of the engineering of steam boilers, an integral part of the working steam fire engine. Dr. Joseph Buchanan in Louisville, KY, “invented and patented a system of spiraling copper tubes, which when preheated, could have cold water injected inside of them with resultant rapid steam.”18 This was important to the development of the fire steamer by allowing the boiler to more quickly heat up and produce effective steam to run the fire pump. Building on Buchanan’s work was Abel Shawk who improved upon the design to produce a boiler that could quickly produce steam. To further develop a steam fire engine, Shawk needed experts in steam engines. Living in Covington, KY he was just across the river from Cincinnati, Ohio, where the Latta Brothers lived and ran a business. The Lattas were steam experts who had designed and built steam railroad locomotives.

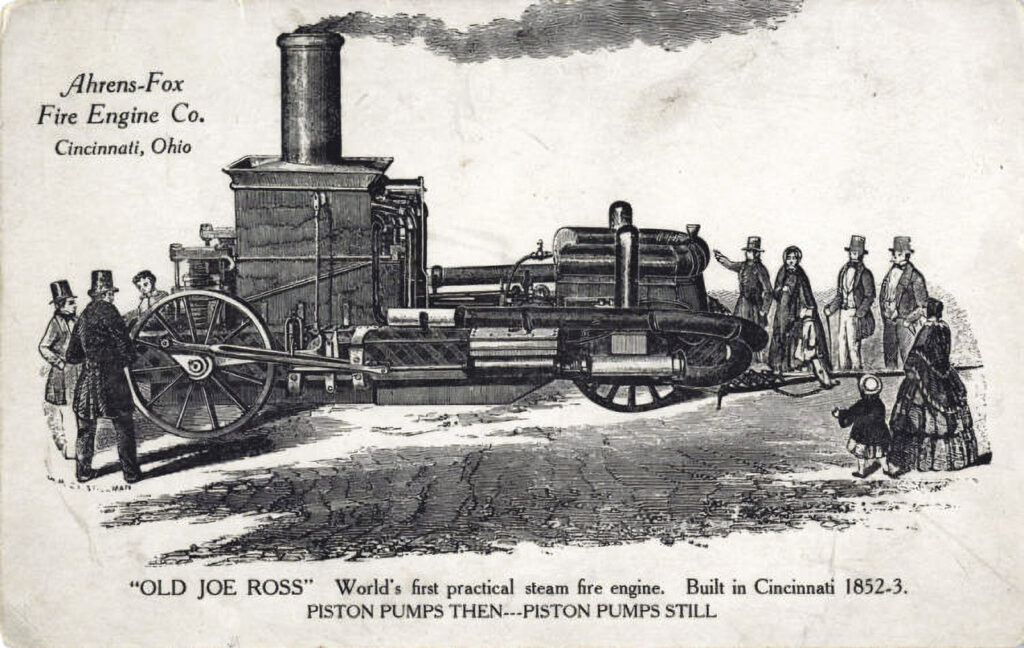

Locating to Cincinnati, Shawk and the Latta Brothers were in the right place at the right time. As mentioned previously, changes were ripe for the fire service, especially in Cincinnati. Fights between fire companies were resulting in riots. In November 1851, a fire occurred in an old planning mill in the city. The volunteer fire companies responded with hand engines and hose carts. Beginning a fight over who reached the fireplug first quickly escalated into a brawl. A second and general alarm brought more firemen to the scene who promptly joined sides in the brawl while the mill burnt to the ground. Naturally, the mayor and city council were appalled by the actions of the firemen. A councilman who was also a volunteer fireman, Miles Greenwood, harshly stated that Cincinnati’s fire companies were a “nursery where the youth of this city are trained in vice, vulgarity, and debauchery.”19 The council wanted to create a paid fire department, who they could control, to solve their dilemma. However, hand engines required large numbers of men to operate them and they couldn’t afford to pay for all the necessary manpower. But, Mayor Taylor was aware of the developments in potential steam fire engines going on in his town with Shawk and the Latta Brothers that could solve the manpower problem of moving to a paid fire department. A test demonstration was arranged in March of 1852 of a prototype engine and it exceeded expectations. The city council approved the construction of the new steam fire engine, and Councilman Joe Ross who was instrumental in persuading the council for the funding would later have the honor of having the engine named after him, “Uncle Joe Ross.”20

The newly completed Latta and Shawk steam fire engine was tested on December 22, 1852, and it easily showed its superiority. In January a test between the new engine and the volunteers was arranged. The volunteers showed up with Cincinnati’s most powerful hand engine, but they could not match the steam fire engine. Uncle Joe Ross was able to shoot three hose streams “over the roof of the four-story Broadway Hotel as the shocked volunteers watched in numbed silence.”21 Though there would still be problems during the transition from volunteer to paid department, the initial step had been taken in changing the fire service, and “Cincinnati became not only the first all-paid fire department in the United States but also the first all-steam fire department in the world.”22

The Evolution of the Steam Fire Engine Manufacturing Business

Shortly after the success of their first fire engine, Shawk and the Lattas parted company. The Lattas went on to make 30 more steamers before their company was bought by Lane and Bodley. Shawk formed the Young America company and built five engines before the company folded.23 Lane & Bodley was primarily a steam sawmill company. They hired, Chris Ahrens, a young German immigrant, to be the superintendent of their fire engine factory. Ahrens also joined the Cincinnati Fire Department. Later he would become a leader in the fire apparatus manufacturing world. Ahrens and Lane & Bodley’s main contribution together in the development of the steam fire engine was changing to steel frames rather than iron, thus greatly reducing the weight of a steam fire engine. In 1867, Lane & Bodley concerned with the growing competition of new fire apparatus manufacturers in the east, decided to sell off the fire engine side of the business. Who would buy the patent rights but Chris Ahrens himself? He formed the C. Ahrens Fire Engine Company and changed the design to eliminate the self-propelled concept and added a fourth wheel. Ahrens left the Cincinnati Fire Department in 1875 and renamed his company the Ahrens Manufacturing Co. Ahrens and dominated the Midwest fire apparatus market with sales to Chicago, Louisville, and St. Louis in addition to Cincinnati.24

Though the major start and continued growth of the steam fire engine business was in Cincinnati, other areas of the country were soon to enter into the manufacturing of steam fire engines. During the steam era of the fire service, there would be over 80 different companies building steamers. A few companies only built a couple of engines before folding. The majority of the others built less than 100. The primary suppliers of steam fire engines in the United States would be through the efforts of eight manufacturers who produced 80% of the steam apparatus.25 We will briefly review these leading manufacturers and the amazing interplay between the companies.

Silsby Manufacturing Company

The firm was originally known as Silsby, Mynderse, & Co. and is located in Seneca Falls, New York. Silsby first started manufacturing hand-pump fire engines in 1845 and built their first steam engine in 1856.26 Silsby steamers used a rotary-style pump that had been invented by employee Birdsill Holly. Silsby engines were highly successful and over 1,000 were produced until 1892 when the company merged with Ahrens and others to form the American Fire Engine Company. The company advertised its steamers as vibration-free when pumping.27

Amoskeag Manufacturing Company

Amoskeag was located in Manchester, New Hampshire beginning in the textile weaving business. They were also involved in building and repairing textile machinery. Their first steam fire engine was built in 1859 and sold to their home city, Manchester. In 1872 they came out with a self-propelled fire engine that weighed over 8 tons. The steamer developed a bad reputation as a “thing of terror” because of its size and street accidents. Very few of the self-propelled models were built. They were successful with their horse-drawn fire engines and sold over 800 steamers. A great improvement in the design of their steamers was incorporated in 1870 with the addition of a “crane-neck” in the frame over the front axle.28 The crane-neck frame design “allowed the turning of the engine in its length (the front wheels pivoted), which was not possible with the straight frame engines then in general use.”29 This was ideal for maneuvering in narrow or crowded streets. The company was bought by Manchester Locomotive Works in 1900, and then by A & B Manufacturing in 1908. Their final engine was produced in 1913.30

Clapp & Jones

The company was founded by Mertilew Clapp and his partner and financier Edward Jones in 1862 in Hudson, New York. Clapp was formerly a Silsby Co. employee who went into business himself. His novel new designs of pumps and boilers created efficient reliable steam fire engines. The company during its operation produced over 600 steamers in various sizes including horse and hand-drawn models. In 1892 the company was acquired by the American Fire Engine Company.31

LaFrance Manufacturing Company

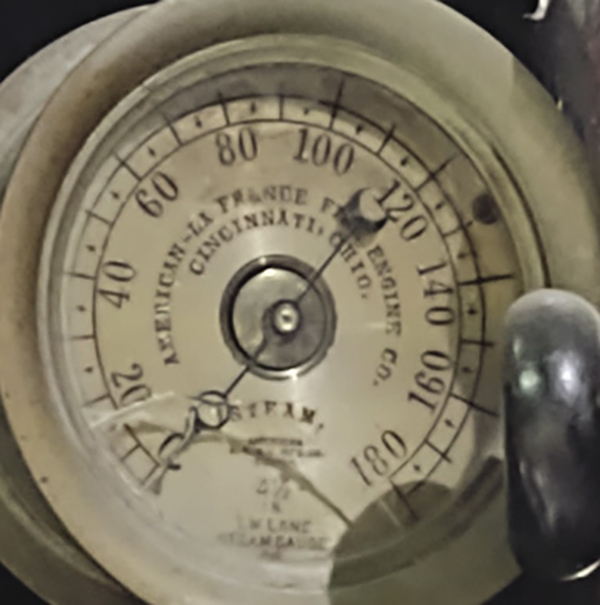

Truckson Hyenveux’s family were immigrants from France who came to America seeking religious freedom. Because of the difficulty in people pronouncing their name, they changed it to LaFrance. Truckson patented a series of improvements on rotary steam engines, and he and several partners went into business as LaFrance Manufacturing Co. in 1873. The company built a variety of mechanized equipment including railroad locomotives, along with steam fire engines. Their original engines had Truckson’s perfected rotary pump, but later they gradually transitioned to piston pumps. In 1900 the company merged with the American Fire Engine Company, which in 1903 became American-LaFrance. The original company produced over 500 steamers.32

Button Fire Engine Company

The company was founded by Lysander Button in 1834 in Waterford, New York, and began as a manufacturer of hand-pump fire engines. The company was able to successfully make the transition in 1862 from hand-pump engines to steam-fire engines. During the company’s run, it had many name changes but the Button Fire Engine name remained for its steamers. The company produced lightweight (2500 pounds) to first class (7000 pounds) steamers. Button steamers used crane neck frames to allow for sharp turns to maneuver. Their pumps were all piston models and could be mounted either horizontally or vertically. The company built over 200 steamers before being combined with other companies to form the American Fire Engine Company in 1891.33

Company Mergers and Partings

With intense competition between the various fire apparatus manufacturing companies, a group of businessmen proposed a merger that would corner the market for fire steamers in the United States. The American Fire Engine Company was created by merging Ahrens, Silsby, Clapp & Jones, and Button companies with Chris Ahrens as president. As part of the merger, the various manufacturing plants were closed except for Ahrens in Cincinnati and Silsby in Seneca Falls, New York. At this time Ahrens brought his two sons, George and John into the business along with his son-in-law Charles Fox. This will come into play later.

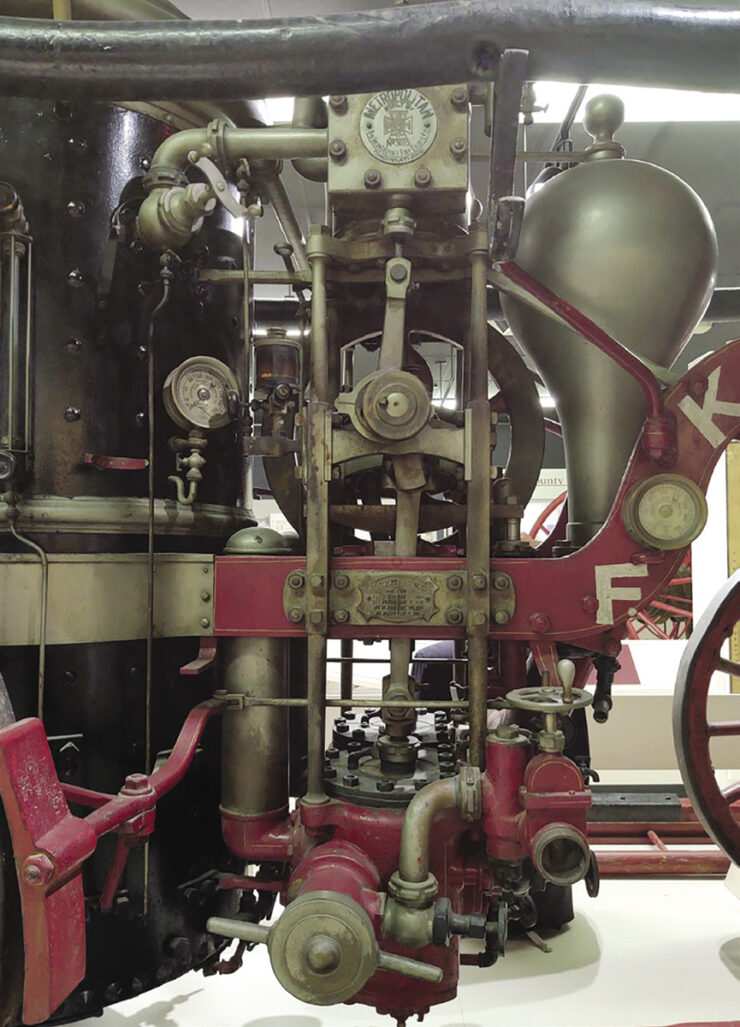

One of the models of steamers developed in 1898 was the Metropolitan. It was considered the ultimate in steamers. The steamers intricate boiler could produce steam from a cold start in two minutes. According to Fred Conway’s book, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, Springfield, Missouri, took delivery in 1903 of a Metropolitan, and The Springfield Republican reported “that the engine throws water high enough for any fire in Springfield.”34

The American Fire Engine Company merged in 1902 with the manufacturer LaFrance to form what would become a major name in fire apparatus manufacturing, the American-LaFrance company. The Ahrens sons, George and John, and brother-in-law Charles Fox left the company and would form the Ahrens Fire Engine Company. That company reorganized in 1911 and became Ahrens-Fox. They went on to produce the next generation of modern motorized fire apparatus.35

Classes of Steam Fire Engines

In the formative years of the steam fire engine business, there was intense competition between the manufacturing companies. There was no standard established for comparing steam fire engines. As one could imagine, each salesman representing a particular brand of steam fire engine would say theirs was the best, most efficient, or could pump more or farther. Some tried to use pump capacity (gallons per minute – GPM) for comparison, while others said apparatus weight was important in that heavier apparatus was more durable and could stand higher stresses. One of the tests that many departments tried was to see how high or far a water stream could be discharged. As a good fire pumper operator knows today, the length and size of the hose, nozzle tip, etc. all have a factor that would affect the fire stream reach. Pumping lower total GPM could make a steamer look better than demonstrating maximum discharge output. Finally, late in the age of steam fire engines, the manufacturers agreed on a basic standardization for sizes and classes. It used the minimum capacity in gallons per minute, and the steamer’s maximum weight as a means of identifying a class or size of the engine. Class and size terms are used interchangeably regarding steam fire engine classification. A fourth-size engine is a much smaller capacity engine than a first or extra-class. However, for a small community, the fourth-class engine might work best with limited manpower, water supply, and narrow or poor street conditions. A table developed from the original data on the standardization of class or size of steam fire engines is included in this article.36

Leading the Way in the West

Missouri was the “Gateway to the West” during the westward expansion of the United States.37 Its cities grew rapidly, and the need for new methods of fire protection was readily apparent. St Louis is a major transportation and shipment hub for westward expansion and became a major metropolitan area on the Mississippi River. Unfortunately, it suffered several devastating fires in the 1800s. This and other factors moved the city to establish a career fire department in 1857. The fire department purchased its first steamers (three) from the Latta brothers that same year.38 They became a major purchaser of steamers from the descendant companies of the Latta Brothers over the years. Continuing this trend, “By 1910 they had 51 horse-drawn steam engine companies.”39 Based on fire apparatus manufacturer companies’ records that were researched in Conway’s book, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, St. Louis would go on to purchase over 80 steam fire engines over the age of steam from various companies.40

St. Joseph was another important Missouri city on the western trail-head, being the starting point for the Pony Express. In May of 1865, the city took acceptance of their first steam fire engine, called the Black Snake.41 According to shipping records for the fire apparatus companies in Conway’s book, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, the steamer would have been a class two Amoskeag Steam Fire Engine.42

Missouri’s State Capitol, Jefferson City, over time suffered many large fires including having the State Capitol building burn twice.43 The city purchased its first steamer in 1871, a third-class Silsby engine. Captain Timothy Young related in his book Capital Smoke that the coming arrival of the steamer was announced in “the Peoples Tribune: A Silsby steam-powered fire engine built in Seneca Falls, New York, will be delivered in thirty days.”44 When the engine arrived and was tested in June 1871, it threw a stream of water “on High Street 250 feet,” and “three streams were thrown 80 feet.”45 In 1883, the State Penitentiary in Jefferson City was almost destroyed by fire. Missouri state government and the penitentiary thanked the city and the E.L. Edward Fire Company for their assistance. As a result of this fire, the “Penitentiary inspectors signed a contract with Ahrens Fox for the purchase of a new fire engine and 1,000 feet of new fire hose.”46

According to manufacturing and shipping records for the fire apparatus companies, Kansas City added its first steamer a class two Silsby in 1868.47 Other Missouri cities that adopted early steam fire engines included: Hannibal with a class two Silsby in 1867; Sedalia with a class three, Silsby in 1868; Louisiana with a Silsby class three in 1870, Macon with a Silsby in 1871, and Canton with a class four Silsby in 1874.48

Working A Steam Fire Engine

One of the better concise descriptions of the working mechanism of the steam fire engine was written by Herbert Jenness in 1909 in his book Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present. Writing about a typical generic steamer, Jenness related:

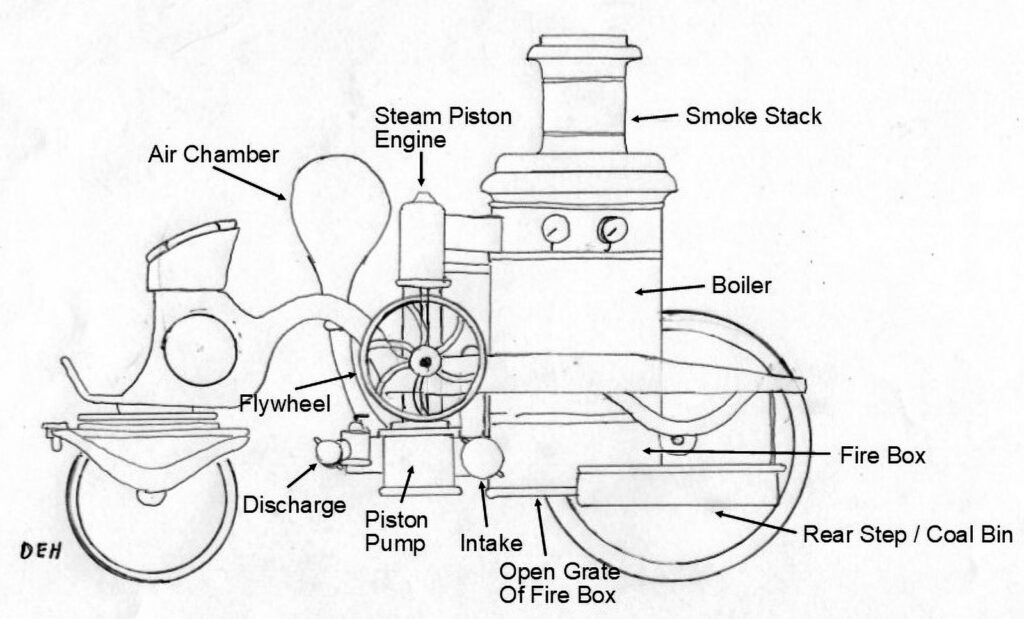

Set between the rear wheels is an upright boiler with a spacious firebox at the bottom and a short smokestack on top. In one of the best-known makes there are two steam-engine cylinders bolted to the front of the boiler, and two pump barrels bolted above them so that the piston rod of the engine is also the pump-rod of pump. The steam drives the piston to and fro in the engine, drawing water through the large suction hose on one side, and forcing it out on the other side through a smaller hose. From the pumps the water is forced into an air chamber, which forms a cushion and serves to equalize the pressure, giving an even distribution to the discharge of water. The principle of these pumps is very much like the pumps of the hand engine, but with tremendously greater power. The products of combustion pass through tubes that are surrounded by water, as in the ordinary boiler of a locomotive. The water tank for supplying the boiler receives its supply through a small pipe connected to or near the suction chamber and pumps. The steam cylinders in the various sizes of these engines range from 6¼ to 10 inches in diameter and have a stroke of 8 inches. To assist the draft and general working of a “steamer,” they exhaust into the smoke stack.49

The steam fire engine was for its day a complicated mechanical device and required a well-trained operator to safely and effectively run it. This would usher in the first truly specialized positions in the fire service. But the job of an engineer, steam engine and pump operator, was not the only specialization.

The following description of the historic operation of a steam fire engine could apply to a career or volunteer fire department of the period. In volunteer departments, they would traditionally have had a couple of full-time people living in the fire station and specially trained to maintain the steamer, house the boiler, and oversee the horses. Or assigned shifts of volunteers. A forerunner of the beginnings of the combination fire department.

The Steam Fire Engine Company Response and Return to Quarters

The response and operation of a steam fire engine required the work of a trained and dedicated team. In addition to the engine, the company team would be the fire company foreman or officer, the pipeman (nozzleman), and other identified positions. But let’s look specifically at the engine company.

Primary to this team was the engineer, who was responsible for overseeing the maintenance of the engine (boiler, steam engine, and pump mechanism). Roper in his 1889 book, Hand-Book of Modern Steam Fire-Engines, said the individuals responsible to operate the steamer should be “practical engineers.”

He further described them as “having a thorough knowledge of steam and steam machinery, and capable of adjusting all the different parts of their engines, and telling whether they are out of order or not.”50 In addition, the engineer should have “good knowledge of hydraulics and hydraulic machines.”51 When the fire alarm was received, the engineer would disconnect any steam lines that pre-heated the boiler, and light the preset fire tender (wood) in the firebox. He would do this using a lighted torch held underneath the open grate at the bottom of the firebox/boiler. This torch could be as simple as a stick with a lighted fuel-soaked rag on the end of it, or a lighted brass boiler hand torch with a fuel-soaked wick in it. The engineer rode the engine on the rear platform behind the boiler. From this position, he will monitor the firebox and begin adding coal as needed (stored in the rear pan or step), while watching and working the boiler valves to build steam pressure. By the time they arrive on the scene, the engineer should have initial steam pressure to begin working the engine. Once on scene, the engineer will also have responsibility for assisting in establishing the water supply to the pump.

The driver is responsible for overseeing the care and condition of the fire horses, though the firemen of the station will assist with feeding and cleaning the horses and stable area. When the fire alarm sounds, the driver will oversee and assist in the harnessing of the horse team and take his place in the driver’s seat at the top front of the steamer. He is trained and experienced as a teamster in the driving of horse teams. On the scene after properly positioning the engine, as regards to water supply and the fire, he will unhitch the horse team from the steamer (leaving the main harnesses on the horses) and lead them a short distance away from the noise and distraction of the scene to rest during the firefighting operation. The driver is always on standby in case the steamer needs to be repositioned because of changing conditions of the fire.

Riding on most steamers will also be a hoseman whose initial job is to assist the engineer in hooking up to a water supply. This may be placing the hard suction hose in a water source such as a cistern or well, or hooking the hose to a pressurized hydrant. Once the connection is made this individual may be assigned to assist the hose company with advancing the hose to the fire or remain with the steamer as a stoker.

The stoker is a fireman assigned to assist the engineer by shoveling coal as needed into the firebox of the steamer to maintain a constant size fire sufficient to produce needed steam pressure. The steamer carries a small amount of coal on the rear platform to add to the fire by the engineer. If there is a large working fire a supply wagon, will be sent to bring coal to the scene and dump it near the rear of each steamer. The supply wagon will also bring wood tender bundles in case a restart is required. The stoker will also assist the engineer in maintaining airflow through the grate in the firebox and removing a buildup of ash and debris underneath the firebox grate of the steamer. The engineer and stoker are also watching to “see what equipment is borrowed” from the steamer, hose tender, or other companies during the fire.52

When the fire is over, the foreman or “officer in command issues orders to ‘take up.”53 The Hose Company will be responsible for recovering the hose, while the Engine Company is responsible for the steamer. Horses are re-hitched to the steamer. A small fire and minimum steam are usually maintained on the steamer until it returns to the house or fire station. This will be used as part of the clean-out and maintenance process on the boiler and steam engine.

Back at the firehouse, some would say the real work begins. Horses are unhitched and usually, the steamer and hose tender are pushed by the firemen back into position in the firehouse to be properly positioned with steam pre-connects and under the hanging harness spreader. This would translate into the tradition in the fire service where upon receiving a new fire engine, the firefighters manually push it into the firehouse, “housing the engine.” Harnesses are cleaned and returned to the quick hitch spreader bars hanging over the horse positions in front of the apparatus. The horses are cleaned and seen too.

The steamer is not only cleaned externally but there is significant maintenance required internally. Using the remaining “steam pressure of about 20 pounds,” the water should be blown out of the boiler “through the blow-off cock … and the boiler refilled with fresh water.”54 The firebox and grate are cleaned and fresh fuel is properly laid in the firebox.

The engine must be properly lubricated. This includes all slide and friction points and also placing oil on top of the steam cylinder pistons and rotating the engine flywheel by hand to coat the inside cylinder walls. If the firehouse is so equipped the engine will be hooked to a stationary steam boiler through quick connects to keep the boiler preheated.

Though the designs of most boilers used in fire steam engines were designed internally to quickly produce sufficient steam to operate the pump, they still required varying times to warm up. They also needed to be protected in cold weather from frost or freezing. To prevent this there were a variety of methods used to preheat the steamer or get a fire going in the boiler quicker. One method was a stationary boiler in the firehouse that could be hooked to the steam lines in the steamer’s boiler through quick-connect fittings to keep the boiler warm and under minimum pressure.55 American Fire Engine Company sold this option with their steamers. Another method was to have a cellar in the firehouse that allowed a radiant heater underneath the boiler where the steamer was positioned. Though the firebox of the boiler was fairly easy to get a fire going through the methods of pre-arranged kindling and wood along with good draft through the bottom grate and up through the smokestack, some departments came up with other options. Some departments had a means of raking coal from the firehouse boiler into a portable firebox that could be slid on a track into the main firebox of the steamer, so a hot coal fire was immediately stoked in the steamer. All innovations came from the manufacturers or firemen to quicken the response from alarm to first water on the fire.

While the engine company has been performing these after-fire duties and maintenance, the hose company was working on cleaning, hanging, and re-loading fresh fire hose on the hose tender (horse-drawn hose wagon or hand-drawn hose cart), but that is another story in itself.

Historic Steamers Today

So where are all the old steam fire engines today? Various sources estimate that in America there were around 5,000 steam fire engines produced during the age of steam in the fire service. According to Conway in his book, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, “less than 400 are known to survive.”56 Existing steamers are usually found in fire museums, the collections of fire buffs, or some have been maintained or restored by their original fire company or its descendant organization. Unfortunately, the vast majority did not survive over time. As the steamers were replaced by the new modern motor-driven apparatus, some steamers were kept for a while as backup apparatus. Eventually, they were all phased out. Along comes World War II and the scrap metal drives to help provide raw materials for producing military arms and vehicles caused steamers to be scrapped.57 Though it is unknown how many steamers succumbed to this fate, there are several fire departments’ oral histories that relate this is what happened.

Fire Museums

Though the ability to have a real antique steam fire apparatus on display is highly prized by fire museums, most do not have one to display due to their rarity. Some fire museums have several in their collection and some instances maintain some as working steamers. The Fire Museum of Maryland in Lutherville, MD, has several steam fire engines including three horse-drawn steamers. The museum conducts an Annual Steam Show that is hosted in the spring where they fire and pump one of their restored steamers. Museum Director and Curator Emeritus Steve Heaver related that it is important to show new generations how historic fire apparatus operated. He said that it takes around two to three hours to perform cleaning and required maintenance to assure the apparatus remains in excellent condition after the steamer is operated. He also related that with historic steamers that are to be operated, many safety devices should be added or modified on the steamer for safety purposes. These include a modern adjustable pop-off safety valve to vent the steam in case of over-pressurization of the boiler and a check valve on the intake of the boiler water feed line. Safety valves should be oriented to vent the discharge of steam away from the operator. When stored on display in the museum, the apparatus should be on jacks to take the weight of the steamer off the wooden wheels to prevent damage over time.58

Regarding purchasing or accepting donated apparatus, Director Heaver commented that it is essential to have an agreement in writing and that every piece of equipment on the apparatus be inventoried and verified, along with pictures for documentation. Even with supposed complete apparatus, antique pieces have disappeared over time, including tools, oil cans, and lanterns.

The Fire Museum Network (FMN) is a non-profit organization that provides a networking opportunity between museums that have fire service-related missions or exhibits. The FMN estimates that “there are over 200 fire museums in the United States and Canada – ranging from a spare room in the firehouse basement to ones with warehouse-like proportions.”59

Even without an actual steamer, it is essential for fire museums or exhibits to honor the significance of the era of steam through informative displays and museum-quality models that bring this exciting time to life for the public, as well as the firefighter. Fire museum historians or curators should be highly knowledgeable regarding steam fire apparatus to relate its significance to visitors on the history and traditions of the fire service.

Fire Collectors

In recent times, there are a substantial number of fire buffs or collectors that have specialized in collecting fire apparatus. How exciting it would be to own an actual piece of fire apparatus? A smaller subset of this group are those people that have a steam fire engine in their collection, probably considered the holy grail of fire apparatus collecting. There are many fire apparatus organizations and among them is the Society for the Preservation and Appreciation of Antique Motor Fire Apparatus in America (SPAAMFAA). They also have regional chapters throughout the US and Canada. They provide many publications and resources for the collector or interested buffs.

One of the privately owned fire steamers that makes numerous appearances across America is the CSFA Antique Steamer. It is operated by the California State Firefighters’ Steamer Team and has been a featured live exhibit at some national fire conferences. The steamer was found and restored by Captain (Ret.) Dave Hubert and his wife Barb. The steamer is completely restored and operational. It is a horse-drawn engine built in 1902 by the American Fire Engine Company. Its story and restoration are documented in a video presentation on DVD entitled, The Steamer: An American Icon, and can be found on the internet for purchase.60

Is it still possible to find a steam fire engine that has been hidden away for years? They are rare but still sometimes surface. Tom Herman, a retired Richmond, VA firefighter and president of the Old Dominion Historical Fire Society, spoke with the author about some of his experiences. After years of following up on rumors of a steam fire engine, he was able to track down a steamer that was stored in a barn. It was supposedly fully operable when it was stored. However, Herman found that during restoration the steam engine had not been properly serviced after use and the steam pistons were rusted solid and had to be refabricated. He also related that it is essential to trace and verify the ownership of the apparatus and properly document its purchase.61

During the research for this history article, the author had the fortunate opportunity to interview some individuals who had experience with firing and operating historic steam fire engines. Their diligent study, research, and apprenticeship led them to become knowledgeable and qualified to operate and maintain restored antique steam fire engines. They willingly shared their experiences in collecting, rebuilding, and operating these important historic fire apparatuses of the age of steam. My utmost respect and appreciation go out to each of them for their willingness to share their knowledge and perspective that contributed to this article.

Resources and Cautions

For the museum curator or conservator of antique fire apparatus, as well as the fire service buff or collector, many resources can be of use in identifying the historical significance, manufacturer, and dates of steam fire apparatus. Among these are two books: Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, by W. Fred Conway, Fire Buff Publishers, New Albany, Indiana, 1997; and History of the American Steam Fire-Engine, by William T. King, Pinkham Press, Boston, MA, 1896, Reprint by Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 2001. A third book for the diehard steam aficionado is the Hand-Book of Modern Steam Fire-Engines, by Stephen Roper and Henry L. Stellwagen, second edition, David McKay Publisher, Philadelphia. PA, 1889, reprint is available through Andesite Press. Even these well-researched works are not the complete definitive resource, but they do provide substantial documented history with corresponding photographs, technical drawings, and other data. Other artifacts in museum collections and archives are original sales and technical literature from the various fire apparatus companies that can assist the researcher. The Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC and the National Fire Heritage Center in Emmitsburg, Maryland contain significant historical fire service artifacts and information in their collections, though somewhat limited in access. Several fire museums throughout the US have collections of steam fire engines and can provide a unique perspective and resource.

Some words of caution. As with the operation of all fire apparatus, safety precautions and prior training are required before attempting to operate them. This is especially true regarding steam-operated fire apparatus. Historically, the steam fire engines “didn’t carry a lot of water [in the boiler]” this was to enable them to heat and produce steam quicker.62 This could create a hazard though if the engine is not properly run with the required water level. In an article in Live Steam Magazine, Stan Pratt with Protection Engine Co. #3 restored their original Silsby Steam Fire Engine, said “If you run a boiler dry, you’ve got a bomb.”63

There is also a possibility that a previous restorer/owner may have altered or retrofitted the components over time. The last thing one would want to have is a catastrophic emergency to occur from the unsafe or improper operation of a steam fire engine that was historically meant to save lives and property. As always in the restoration or retrofit of antique fire apparatus or components, a modification may affect the provenance or historical importance of the fire apparatus.

It should be understood that this article does not provide the necessary knowledge and practical training experience to teach one how to safely fire and operate a steam fire engine and boiler, nor should it be substituted for appropriate instruction and apprenticeship under the supervision of a qualified and experienced steam fire engine engineer.

The Legacy of Change and Traditions

During the Industrial Revolution, it should be mentioned that there was another type of fire apparatus that became prominent, the chemical fire engine. It served a need in some smaller communities, and in some cases served alongside steam fire apparatus in larger departments. Though it was an alternative method of firefighting, in historical references this type of apparatus was never as highly regarded as the steamer. But that is a different story in the history of the fire service for a later time.

Though the era of the steam fire engine would only last about 65 years, its contribution and impact on the fire service was far-reaching. By reducing the number of personnel needed to effectively fight a fire, the steamer was the main impetus in the creation of the career fire service. It also laid the groundwork for a change in staffing, specialization, operations, and modern tactics. In so doing it forever changed the history of the fire service and established new traditions.

Herbert Jenness predicted the demise of the age of steam fire engines in his book Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present. Back in 1909, he wrote:

“The growing popularity of automobile fire-wagons…predict the ultimate disuse of the steam fire-engine. Like the “hand-engine,” which was crowded aside by the “Steamer,” so also will this time-tried and true, invaluable and the venerable machine gradually give place to more modern inventions.”64

And so it was that in the 1920s, steamers would switch from horse-drawn to motor-drawn apparatus, replacing the romantic era of the fire horse. This was the first step that would later lead to the demise of the steamer itself and the passing of the age of steam in the fire service. Ultimately the internal combustion engine-powered fire apparatus, running both the drive gear and the pump, would be the latest technology that would usher in the age of motorized fire apparatus. But even with this advancement in fire protection, firefighters would still fondly remember the romantic period of the age of steam and the sturdy graceful horses and gleaming, smoking, steamer as it raced to save life and property. Jenness would make another prediction regarding the future generations in the fire service:

“The Steam fire engine will always be a leading subject, demanding a conspicuous position in the history of fire department enterprise and progress.”65

This prediction also came true, as we look back with pride at the firefighters that have gone before us. They overcame the fear of change and embraced new technology that would enhance their capabilities to perform their mission. Though our technology and techniques continue to change to embrace improvements in fire protection, our history and tradition of the protection of life and property remain the overarching tenant of the fire service. As we remember our past, we continue to honor and observe the grand history and traditions of the early American fire service, as it guides us in our future valiant endeavors.

Author’s Comments:

The author wishes to recognize and thank the fire service personnel and organizations for their assistance in the development of this article. In particular, the author expresses his appreciation to: Chief William D. “Bill” Killen, CFO, FIFireE, Past President/CEO, National Fire Heritage Center; Steve Heaver, Director and Curator Emeritus Fire Museum of Maryland; Tom Herman, President Old Dominion Historical Fire Society and FF (Ret.) Richmond (VA) Fire Department; Eriks Gabliks, Superintendent U.S. National Fire Academy; Doug Kahn, NFA Faculty and Gettysburg Fire Department; Rick Webb, President, Metro Kansas City Chapter of SPAAMFAA, Harry S. Truman Independence ‘76 Fire Company; David Hartman, Museum Curator, Wyandotte County Historical Museum; Steve Holtmeier, Jefferson City Fire Museum; Chief (Ret.) David Hall, Springfield Fire Dept. Museum; NFA Learning Resource Center; and the University of Missouri Ellis Library/Lending Library for assisting the author in obtaining the inter-library loan of various research documents and archival materials.

Photos

All photos are credited within captions, taken by author or considered public domain.

Endnotes

1

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Steam engine.” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 26, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/technology/steam-engine, Accessed Sept. 12, 2022.

2

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Industrial Revolution”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 13 Mar. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution. Accessed July 12, 2022.

3

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Heron of Alexandria.” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 15, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Heron-of-Alexandria, Accessed Sept. 12, 2022.

4

Robert Angus Buchanan “history of technology, The Industrial Revolution (1750–1900)”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 16 Jun. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/technology/history-of-technology. Accessed Sept. 21 2022.

5 Ibid.

6

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “John Blenkinsop.” Encyclopedia Britannica, January 19, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Blenkinsop. Accessed September 12, 2022.

7

W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, Fire Buff Publishers, New Albany, Indiana, 1997, p. 12.

8

Ibid.

9

Editors of Country Beautiful, Great Fires of America, Country Beautiful Corporation, Waukesha, Wisconsin, 1973, p. 43.

10

William T. King, History of the American Steam Fire Engine, Originally published by The Pinkham Press, Boston, 1896, current edition: Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 2001, p. 2.

11

Ibid.

12

Ibid.

13

Ibid.

14 Ibid, p. 4.

15 Ibid, p. 5.

16 Ibid, p. 6.

17 Ibid, p. 7.

18

W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 15.

19 Ibid, p. 14.

20 Ibid, p. 16.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid, p. 18.

23 Ibid, p. 19.

24 Ibid, p. 21.

25 Ibid, p. 34.

26

William T. King, History of the American Steam Fire Engine, p. 21.

27

W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 59.

28

William T. King, History of the American Steam Fire-Engine, p. 56.

29

“Engine Co. 10 (Fire Companies)”, Boston Fire Historical Society, Official Website: https://bostonfirehistory.org/fire-companies/engine-co-fire-companies/engine-co-10-fire-companies/. Accessed October 14, 2022.

30

W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 75.

31 Ibid, p. 85.

32 Ibid, p. 95.

33 Ibid, p. 103.

34 Ibid, p. 23.

35 Ibid.

36

Information on the Classes of Steam Fire Engines and the related table are based on reference material from the following sources: W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 41; Frank D. Graham, M.S., M.E., “Steam Fire Engines”, Audels Engineers and Mechanics Guide 2, Theo Audel & Co., New York, 1921; and Fire Engineering Staff, Classification of Steam Fire Engines”, Fire Engineering Magazine Archives, April 10, 1886, https://www.fireengineering.com/leadership/classification-of-steam-fire-engines/#gref. Accessed 9/24/22.

37

K.E. Walsh, “Why Is St. Louis Called the ‘Gateway to the West’?”, United States Now. Website: https://www.unitedstatesnow.org/why-is-st-louis-called-the-gateway-to-the-west.htm. Accessed October 18, 2022.

38

W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 220.

39

Bill Westhoff, A Tribute to the Fire Service of Missouri, Walsworth Publishing, Co., Marceline, Missouri, first edition, 2018, p. 119.

40

Compiled from data listed in “Steamer Shipping Records”, obtained from the book by W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, Fire Buff Publishers, New Albany, Indiana, 1997, p. 220-289.

41

Bill Westhoff, A Tribute to the Fire Service of Missouri, p. 111.

42

W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 283.

43

“What is the history of the Missouri State Capitol?”, Missouri History, Missouri Secretary of State Website: https://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/history/capitol.asp. Accessed October 18, 2022.

44

Timothy Young, Captain, Capital Smoke, The Life and Times of the Jefferson City, Missouri Fire Department, Walsworth Publishing, Co., Marceline, Missouri, 2013. P. 8.

45

Ibid.

46

Ibid, p. 13.

47

W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 283.

48

Compiled from data listed in “Steamer Shipping Records”, obtained from the book by W. Fred Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, Fire Buff Publishers, New Albany, Indiana, 1997, p. 220-289.

49

Herbert Theodore Jenness, Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present, Cambridge, Mass, 1909, p. 47.

50

Stephen Roper and Henry L. Stellwagen, Hand-Book of Modern Steam Fire-Engines. Second Edition, David McKay Publisher, Philadelphia. PA, 1889, p. 111.

51

Ibid.

52 Ibid, p. 126-127.

53 Ibid.

54

William T. King, History of the American Steam Fire-Engine, p. 149.

55

M.W. Goodman, M.D., Inventing the American Fire Engine – An Illustrated History of Patented Ideas for Fire Pumpers, Fire Buff Publishers, New Albany, IN, 1994, p. 55.

56

Conway, Those Magnificent Old Steam Fire Engines, p. 153.

57

Ibid, p. 154.

58

Telephone interview with Steve Heaver, Director and Curator Emeritus Fire Museum of Maryland, conducted by author Sept. 27 and Oct. 27, 2022.

59

Museums USA, Fire Museum Network, webpage: https://www.museumsusa.org/assocs/info/1603. Accessed October 17, 2022.

60

Steve Morse (Writer/Director), The Steamer: An American Icon, Hubie Fire Pictures, Deer Valley Press, Santa Barbara, CA, website: https://hubiepictures.com/, 2011.

61

Telephone interview with Tom Herman, FF (Ret.) Richmond (VA) Fire Dept., President Old Dominion Historical Fire Society, and collector, conducted by author Sept. 19, and Oct. 27, 2022.

62

Robert J. Tomaine, “The A.M. Atkinson”, Live Steam, Village Press, Inc., Traverse City, MI, Volume 29, Number 5, September/October 1995, p. 16.

63

Ibid.

64

Herbert Theodore Jenness, Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present, p. 48.

65 Ibid, p. 49.