In the book, Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present, Herbert Jenness related that early American colonists understood that a major conflagration could be prevented “in a few seconds by the earnest and well-directed work of one cool-headed man with a single pail of water.”1 Thus the concept of fire buckets and bucket brigades for community fire protection was conceived.

In the early days of colonial America, a fire bucket was one of the first pieces of firefighting equipment. American communities and towns experienced the constant hazard of the spread of unrestrained fires. Because of this, they passed laws requiring each home and business to have fire buckets to quickly extinguish a fire. One of the first fire ordinances in America was adopted in New Amsterdam, New York, in 1648 that instituted certain building codes and provided for leather fire buckets and other equipment.2 Fire buckets were traditionally made from leather and were painted with a base coat to keep them waterproof along with the insides being coated with tallow and/or wax. They had a rope or leather-covered rope handle to aid in carrying the bucket. The handle was generally secured to “D” shaped iron rings that were attached to leather lugs on opposite sides of the rim.

Leather Fire Buckets

Fire buckets were constructed by resident leather artisans as required to support the needs of the local community. Though the basic design was similar during colonial times, each artisan formed and sewed the buckets they produced in their own way. The general size of leather fire buckets was approximately 13 inches tall by 8.5 inches wide at the rim, and depending on size and design the capacity ranged from one and a half to three gallons of water. A collection of antique fire buckets at the George Washington Mount Vernon museum included buckets from 1797 that were 13 inches high with an overall diameter at the rim of 8 inches.3

Portsmouth Federal Fire Society historian, Peter Lamb, provided a basic description of how the leather fire bucket was made. He said fire buckets:

Were typically made from heavy “vegetable tanned” cowhide taken from the animal’s shoulder where hides are the most consistent and free of blemishes. Each piece is then soaked and stretched around a tapered wooden mold. Once dry it is hand-stitched in the two-needle “whip stitch” method. The top rim gets folded down over a flat wooden hoop and stitched to give the bucket strength and form. The handle, with a rope core, is attached by two wrought-iron rings that allow the bucket to pivot and swing when being filled and emptied with water.4

Interestingly, the local leather artisans or merchant craftsmen for the most part did not mark or stamp their buckets with their name or makers mark, so usually, when an antique bucket is found, the bucket maker is unknown. An example exception to this occurred in Boston with buckets made by John Fenno, Jr. Mr. Fenno was a leather craftsman in Boston who operated a business making and selling leather goods, including boots, shoes, leather buckets and eventually leather fire hose. His fire buckets were marked with “a rectangular stamp reading ‘J. FENNO’ on the back of his buckets near the stitched seam.“5 He even advertised in the Massachusetts Centinel in April 1785, saying, “John Fenno, jun. Hereby gives notice to those gentlemen who are so well disposed as to enter into Fire Societies, and all others, that he continues to make Leather Buckets, strong and neat, of a large size, and handsome shape.”6 There is some indication that other artisans may have attached a printed paper label to their buckets when sold, but few of these labels have survived the years.

Individually owned fire buckets generally had the owner’s last name painted somewhere on the bucket to identify it. If residents were required to have more than one bucket then each bucket was also numbered. In some cases, fire buckets were highly decorated with a coat of arms, patriotic scenes, or a fire society’s emblem to help identify them. Organized fire societies were often well-recognized civic groups made up of the community’s leading citizens for the purposes of fire protection. It was an honor to be selected as a member of these societies and therefore the members proudly displayed their membership through specially painted fire buckets. The historic folk art found on fire buckets adds to its provenance and the collectors’ value in modern times.

The Fire Bucket in Use

To combat a fire, “bucket brigades” were commonly organized and consisted of two lines of people stretching from the town well or water source to the fire. They passed buckets of water to the fire, where the water was literally thrown from the bucket onto the flames. The empty buckets were passed back by an adjacent line of people to the well to be refilled. Even though this means of fighting fire was rudimentary at best, it was at least a minimal level of fire protection. A fire could quickly spread completely devastating a community, burning out homes and businesses alike. In the early days before fire companies were formed, a fire event was an all citizens emergency. In many cases, women and children filled in on the bucket brigade line helping pass the empty buckets back to the water source.

With the development of hand-pumped fire engines to squirt water on fires, the fire bucket was still needed. The early hand pumper was mounted above a box or container that held water to be siphoned up by the pump. To keep the pump box filled, the bucket brigade was employed to transfer water from the water source to the fire engine, and there to be pumped on the fire. Bucket brigades remained a crucial component until the invention of pressurized fire mains and leather fire hoses. With these new developments, a fire hose could be run from the fire main or pumper at the water source to supply water to the front line fire engine.

Fire or bucket brigade members were required to respond quickly when the alarm bell rang and had to bring their bucket(s) with them. After the fire, buckets marked with the owner’s names were collected and returned to their owners or dropped off at a central point like a church for the owner to collect. As more formal “fire brigades” were formed, fire companies would stockpile buckets and transport them to the fire. The fire company’s buckets had the name or symbol/emblem of the fire protection society painted on the bucket for identification.

Many communities instituted ordinances or laws regarding the number of fire buckets homes and businesses should have and use. Penalty fines were established to ensure compliance. As an example, the City of Hartford, Connecticut, instituted “a fine of $1.00 per violation, for any person failing to convey their buckets to the scene of a nearby fire.”7 A pretty hefty sum for 1815.

Rubber Buckets

During the mid-1800s a new option for the construction of fire buckets came about with the development of the rubber vulcanization process by Charles Goodyear. The process allowed for the production of durable, long-lasting rubber products. Though leather fire buckets were quite durable over time, they were subject to rot. Goodyear used his process to make rubberized canvas buckets for fire and other uses and was sold by the Goodyear Rubber Company.8 Relics that survive show that these buckets were sometimes also painted or personalized by the owners.

Metal Buckets

Despite the institution of organized firefighting companies and the introduction of more modern equipment, fire buckets continued to be a dependable low tech first response solution for firefighting available to the public and business and industry. As metal became used for more items, the industrialization of manufacturing processes resulted in the development of metal fire buckets. Similar in design and function to the leather fire bucket, the metal fire bucket was made of metal, tin, or galvanized metal, with a wire hoop handle. The bucket part is generally tapered from the top toward the bottom so they could be stacked together for storage. Gone were the ornately painted scenes, coats of arms, or individual identifying marks, and replaced with a red painted bucket and generally the word “FIRE” painted or stenciled on them in black letters. Some galvanized buckets were left natural finish and the word “FIRE” painted in red to identify them as a firefighting device.

As in the history of the fire service and antique firefighting equipment, there is almost always some controversy. Here is one of the controversial items concerning fire buckets. With the introduction of metal buckets, more design options were available. In some cases, additional handles were added to the side or bottom of the bucket to facilitate the throwing of water on the fire. A major change was a number of buckets were produced with rounded bottoms. The question is why was this feature introduced? There are various internet sites, and articles that give competing versions of the answer. One version is that though the buckets were massed produced by this time and fairly cheap, they were also a really nice handy bucket that could be used for other tasks, especially on the farm. So the story goes that the rounded bottom was added so that the bucket would not sit upright on the ground but fall over. Making it ineffective for common chores, and thus less likely to be stolen. Another reason given was that there was actually some thought put into the actual design of fire buckets. The rounded bottom was added to make the bucket easier to tip over when dunked into a barrel or water source and therefore more quickly fill. A variation of this was that the design allowed the water in the bucket to be more efficiently directed at the fire when thrown from the bucket. As far as I can find there is not a definitive answer to the reason for the rounded bottom being designed into the bucket. Based on throwing some water from both types of buckets, I would say that they both throw water about the same. So, the concept of a round bottom bucket for discouraging theft seems more realistic. Or maybe it was just a marketing ploy to sell new buckets?

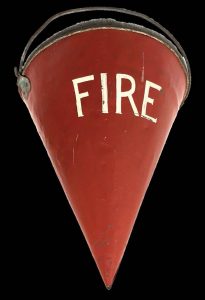

Cone Shaped Fire Buckets

If you are a true fire service collector or historian, you have probably come across the odd-shaped conical fire bucket. Though they may have been plentiful at one time they are not commonly seen anymore. They were made of galvanized steel, to prevent rust, and shaped like a wide-mouthed cone tapered to a pointed end. They had a metal bale or handle at the wide circular end of the cone. The cone was approximately 14 inches tall and 15 inches wide at the rim. They were usually natural galvanized metal finish with the word “FIRE” painted in red or black by the use of a stencil. Some were painted red and the word “FIRE” stenciled in black or white. The bale folded down to the rim and they could be stacked inside each other for compact storage. Though they may have been found in the manufacturing industry, they were primarily used by the railroads as a low-tech means of fire protection. They could be used to contain either water or sand. One story is that the cone design comes from ships that sewed canvas cone-shaped buckets for use on the ship for fires. Though the reason for their shape is also not well documented, it is assumed the design allowed for easy construction, they readily stacked together for space savings, and the design prevented excess “sloshing” of water or sand when hung on brackets in railcars or cabooses. Some accounts relate that the pointed end of the cone allowed easier gripping as the water from the bucket was thrown on the fire. Also, the pointed end prevented people from turning the bucket upside down, dumping its contents, and sitting on it. The use by railroads is documented in Rock Island Railroad Rules that says when shipping cotton bales the railroad station should have “a sufficient number of barrels filled with water, each equipped with two cone-shaped fire buckets.” Each station and caboose was to be equipped with “two cone-shaped fire buckets to be used in fighting fire.”9

The Legacy of the Fire Bucket

So what happened to bucket brigades and the fire bucket? With the coming of modern fire protection components to local communities like water systems, fire hoses, steam-operated fire engines, and organized fire departments, the need for bucket brigades came to an end by the mid to late 1800s. Fire buckets for first response and individual fire protection were replaced by more efficient and affordable fire extinguishers, such as soda acid, individual hand pump cans, or dry chemical extinguishers. Metal buckets can still be found occasionally in some areas as a low-tech means of first response fire protection. However, they are usually filled with sand and there to extinguish incendiaries (smoking materials).

Antique leather fire buckets are greatly prized as display items by fire service buffs and collectors. They are also prized by historians and collectors of colonial history because of the graphic folk art or insignia of historic colonial volunteer fire companies painted on them. Because of this, it has become increasingly difficult for the fire service historian to find reasonably priced original antique fire buckets. Though there are several current leather companies and traditional artisans that produce reproduction fire buckets, the reproductions are still relatively expensive when made out of real leather and accurately constructed.

Fire buckets are a unique part of fire service history. They are an essential part of fire equipment collections or fire museum displays in that they effectively highlight the transition from the early days of manual fire protection to more modern fire equipment. The image of the iconic fire bucket recalls the days of derring-do when local citizens came to the aid of their neighbors to fight a fire and save lives. This concept of service above one’s self would lay the foundation of what would become the awe-inspiring American Fire Service.

Endnotes

1 Herbert Theodore Jenness, Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present, Cambridge, Mass, 1909, p 5.

2 Ibid, p 2.

3 George Washington Mount Vernon Museum, website page accessed Oct. 2021, emuseum.mountvernon.org/objects/686/fire-bucket;jsessionid=70559805E4C18E99B549A21001C28EB8?ctx=2d12bac45b0f21829a2f0bb5781b02843e089aa5&idx=2

4 J. Dennis Robinson, Federal Fire Society Adds to Its Bucket List (web article), Robinson’s history column, Portsmouth Herald, 2012, www.seacoastnh.com/federal-fire-society-adds-to-its-bucket-list/

5 Christopher D. Fox, “Fire Buckets in 18th Century Boston”, Internet post May 7, 2020, Skinner Inc. Auctions, website: www.skinnerinc.com/news/blog/fire-buckets-in-18th-century-boston/ .

6 Ibid

7 Alex Dubois, “Inside the Collections – Fighting Fires in Early America, Story 2 Town Planning”, My Country Blog – Litchfield Historical Society, April 1, 2020, website article: blog.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/?p=989 .

8 “Fire Bucket, Goodyear 13” online article, Smithsonian Institute, National Museum of American History, americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1340622.

9 Rock Island Employee’s’ Magazine, Volume 6, No. 4, October 1912, Rule 1, page 13, (Multiple issues compiled in book form).