A Part of Fire Service History

Today’s Fire Service has as part of its strategy for dealing with fires and others emergency the concept of early notification and quick response. This enables the fire department to quickly react thus enhancing the ability to save lives and protect property from fires and other emergencies. Many younger Firefighters may think this all started with the implementation of the 911 calling (dial) system in 1968, however, there is a rich history to the early development of fire alarms and quick notification.1

With a significant increase in enhanced 911 capabilities in many communities today, an individual can quickly access emergency services through their cell phone and get a rapid response direct to their location. With most people being connected electronically through cell and internet technology, they have ready communications no matter their location. Gone are the days of trying to find a working pay phone in a phone booth. With the advanced computer, cellular technology, and satellite GPS, the emergency tele-communicator or dispatcher can in most cases identify the caller, phone number, and the caller’s location through the enhanced 911 computer programs. Dispatchers used to have to ask all these questions verbally as part of taking the emergency call. These enhanced capabilities have speeded up the notification process and the accuracy of locating the emergency event. But this capability took a long time to develop and can be traced back through history to the early beginning of the fire alarm telegraph system. A few of the older veteran firefighters will recall the red fire alarm boxes that were stationed on most street corners in medium to large cities back in the day.

This article will cover some of the historic developments in fire alarm notification that led to early notification and quick response to fire alarms. This history also helps us understand how today’s fire departments dispatching and response is based on these historic procedures and established part of our fire service tradition. We will also learn the significant role the City of St. Louis, MO, played in the beginning days of the fire alarm telegraph system.

Early Fire Alarms and Changing Times

In previous articles in this fire service history series, we have covered some of the early methods of fire alarm notification. In the Colonial days the alarm was spread from person to person by shouting FIRE, followed by “Throw out your buckets” alerted the citizenry to a fire.2 Then came the fire watch, called “Prowlers”3, or “rattle watch”4 ringing hand bells, muffin bells, or using fire rattles. As time progressed some communities began using fixed bells in churches or government buildings as part of the fire alarm notification process.5 All these were initial efforts directed at alerting the nearest citizens and thus spreading the alarm to eventually alert the bucket brigade or fire society/company to respond and fight the fire. However, this was not a very efficient means of getting the alarm message to the fire service personnel and organizing a response especially as cities and communities began to grow and expand.

In History, the mid 1700s to 1800s is considered the time of the “Industrial Revolution”. Beginning in Great Britain and spreading to America, this time period marks a “change from an agrarian and handicraft economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacturing. These technological changes introduced novel ways of working and living and fundamentally transformed society.”6 The development of these new technologies led to new ways of applying them to address old problems and improve life and safety. One of these new technologies that would be adapted to improve fire protection was the electric telegraph.

The “electromagnetic communication device” (telegraph) was invented by Samuel F. B. Morse in 1835, and used Morse Code “to represent letters and numbers” for sending messages.7 The public use of Morse’s telegraph system began in 1844.8 This provided a novel new communication method well before the development of the telephone. The telegraph provided almost instant electronic transmission of messages via Morse Code, wherever telegraph wires were installed. The adaptation of this communication method for transmitting fire alarms would have a far reaching impact on the fire service for over 100 years.

The first known use of the telegraph to transmit notification of a fire was in New York. In 1845, New York installed fire watch/bell towers in each of the eight fire districts that covered the city.9 These bell towers were staffed by watchmen who would visually look for fires and sound the alarm by ringing the bell when a fire was spotted. To help firemen know which direction the fire was, the watchman would either lean out the window and point in the direction of the fire or hang a flag during the day or lantern at night.10 Within a year, “the towers were connected by telegraph; fire service alarms further enhancing the capability of the system to spread alarms faster and, concurrently, the response of firemen.”11 With the enhancement of the telegraph communications between watch towers, they could notify all the towers as to a fire and location. According to Paul Ditzel, in his book Fire Alarm, Charles Robinson in 1850 was the first person to transmit alarms in New York through the Morse telegraph system. Shortly thereafter firehouses were added to the telegraph system.12 Though these enhancements improved the discovery of a fire and alerting of firemen, it still required a watchmen or fireman to visually see a fire from a distance away and sound the alarm about a general location. This deficiency allowed many fires to grow in size and scope before the alarm was sounded. There was still a need for a better quick acting alarm system.

Key Individuals in the History of the Fire Alarm Telegraph System

Samuel Morse’s invention of the “electromagnetic communication device” (telegraph) had initiated a new period in potential communications for the fire service, but it would need a visionary and some inventive people to bring forth a working fire alarm notification system. A number of these individuals we will find were inter-related in their quest to bring this vision to success.

Dr. William Channing

Though Samuel Morse may have considered the transmission of fire alarms as one of the possibilities for his new electromagnetic communications device, the person that is credited with envisioning this concept was Dr. William F, Channing. Dr. Channing was a medical physician receiving his degree from the University of Pennsylvania. However, “he never practiced medicine perhaps distracted from his true passion electrical sciences and telegraphy.”13 Dr. Channing explained in a newspaper article in the Boston Daily Advertiser how a fire alarm system could be built and operate. His explanation included the “arrangement of signals, fire alarm boxes, and a central station.”14 He was able to convince the government of Boston to fund the building of a system in 1851. Probably his greatest impact on the American fire alarm system came about from his lecture, The American Fire-Alarm Telegraph that he delivered at the Smithsonian Institute in March 1855. With his presentation being “reprinted in the Ninth Annual Report of the Board of the Smithsonian Institution, 1855, assured him even greater attention.”15 Dr. Channing conceived of his idea for the fire alarm telegraph system at the age of nineteen, and his remarkable vision of its importance made him “truly the Father of the Fire Alarm Telegraph.”16 From the installation of the first fire alarm system in Boston, Dr. Channing obtained a number of patents sharing some with Moses Farmer, who we will review next.

An additional historical footnote is that present at Dr. Channing’s original lecture, besides many businessmen, was John Gamewell. Little did anyone realize that “the Gamewell name soon would become synonymous, even generic, to police and fire alarm telegraphy.”17 More on Gamewell later.

Moses Farmer

Working with Channing on the first city fire alarm system was Moses Gerrish Farmer. Farmer was an early pioneer in electrical engineering. In 1851, his work in the field lead to the important principal for “transmitting the alarm from box to central station.”18 The Boston City Council appointed him to oversee the installation of the first fire alarm system as the Superintendent of the system. After the success of the Boston system, Dr. Channing and Farmer were issued a patent on May 19, 1857 for the first fire alarm system. They shared a patent on the fire alarm repeater.19 Farmer also received patents for a variety improvements in electro-magnetic alarm bells and galvanic batteries. According to Roncallo, in his book History of the Fire Alarm and Police Telegraph, the first fire alarm system in the country would not have been a success, “had it not been for the genius of Moses G. Farmer, as superintendent of construction, conferring with Dr. Channing.”20

John Gamewell

John Nelson Gamewell was from Camden, South Carolina. He was the son of a Methodist minister. When his father-in-law became ill he took over his job as the community’s postmaster and the agent in charge of the local telegraph office.21 His trip to hear Dr. Channing’s lecture, covered previously, was perhaps inspired by his burgeoning hobby as an amateur telegrapher and now new job.

Returning home from his Smithsonian trip, Gamewell sought funding assistance from his friend James Dunlap and “purchased the rights for fire alarm installations in the Southern and Western states for $10,000. In May 1959, Gamewell and Dunlap purchased the remaining rights for $27,000.”22 But there is more to the story before Gamewell achieved success. Gamewell was a southerner and ended up serving in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Because of this, the U.S. Government confiscated his fire alarm patent rights and auctioned them off in May 1863. John F. Kennard acquired the patent rights for a reported $80.23 After the Civil War Kennard transferred most of the patent rights back to Gamewell, and an 1865 patent agreement between Kennard and Company and John N. Gamewell and Company was reached for the sum of one dollar.24 Eventually through buyouts and other acquisitions, and transitions, the company was reorganized and in 1879 became the Gamewell Fire Alarm Telegraph Company. A number of other inventors would contribute to the success of Gamewell’s company along the way. John N. Gamewell died on July 19, 1896. According to Roncallo, in his book History of the Fire Alarm and Police Telegraph, when Gamewell died, “more than ninety percent of the alarm systems in service had his name on them.”25

Moses Crane

One of the people that contributed to Gamewell’s success was Moses Griffin Crane. Crane had a natural mechanical ability and was a maker of regulators and town clocks. He and his father Aaron Crane went to work for the Turret and Marine Clock Company in 1856 in Boston. The Turret Company and a number of others produced fog and fire alarm bell striking machines under a patent held by Arron Crane. In 1868 Moses Crane patented his electro-mechanical gong. A year later he patented a non-interference Signal Box. Eventually most of the Crane Company’s business was manufacturing components for Gamewell. And in 1875, Crane joined with “Gamewell in patenting a fire alarm repeater, which was of major importance.”26 For a while the two companies of Crane and Gamewell were intermingled. In 1886, Crane sold out to Gamewell for $47,000, agreeing not to compete in fire and police telegraph systems for 10 years.”27 Five years later, in 1891, Crane went back in business with the Municipal Fire & Police Telegraph Company. He installed a fire alarm system in his hometown of Newton. However, he found it difficult to compete with Gamewell, and “depressed by legal litigations…Crane died of a self-inflicted gunshot” in 1898.28 Because of the importance of his contributions to the developments in fire alarm systems and the rarity of the Municipal Fire & Police Telegraph Company boxes and components, these items are highly prized by museums and considered valuable fire service antiques.

James Gardiner

Though there are several other people noted for helping develop and build the early fire alarm systems, we will mention one more here. James M. Gardiner was a clockmaker by trade and from St. Louis, MO. He was also brother-in-law to John Gamewell and started working with him in 1856. One can imagine his contribution to the development of the clockwork like mechanisms of the early fire alarm boxes. Gardiner was chosen to supervise the construction and installation of the first Gamewell system in St. Louis (the third fire alarm system installed in the U.S.). Gardiner went on to become a principal in the Gamewell Company in 1869, and providing many improvements, including inventing a non-interfering mechanism.29

Now that we have examined some of the key people in the development of the fire alarm telegraph system, we will next review some of the early systems and the influential changes and contributions during this important period in fire service history.

Developments in the Early Fire Alarm Telegraph System

As previously mentioned, New York City was the first to use Morse’s telegraph to link communication between their fire watch/bell towers. However, they had not yet gone a step further to develop the use of citizen activated local fire alarm boxes. New York did continue to develop their own fire alerting system, and in 1869 awarded a fire alarm telegraph box contract to Charles Chester, who had established a relationship with Gamewell.30 Chester did develop several patents improving on components of the fire alarm system with Charles Robinson.

As related previously, the first fire alarm telegraph box system was installed in Boston, MA being motivated by Dr, Channing and Moses Farmer. Boston’s fire alarm system “was put into service on April 28, 1852, at noon.”31

The second city to install a fire alarm call box system was Philadelphia, PA. In 1854 the city authorized a Special Committee to study the need for a fire alarm and police telegraph system. They visited New York with their telegraph and watch/bell tower system and Boston with the system being developed by Dr. Channing and Farmer. They chose the Boston concept but ended up using local contractors W.J. Phillips and J.H. Purdy to build the system after purchasing the rights from Dr. Channing and Farmer. They locally produced the components for their system that went in service in 1855.32

The third city in the United States to install a fire alarm box system was St. Louis, MO. The Board of Aldermen voted to expend the funding for an alarm system in July 1856. Gamewell was chosen to install the system with the patent rights he had already purchased from Channing. Gamewell used his brother-in-law James Gardiner of St. Louis to supervise the system installation. The fire alarm boxes went in service on February 22, 1858.33 Though an early book on the history of the St. Louis Fire Department identifies them as the second city to try a fire alarm system, based on researched time lines they were the third. The historical significance though was that St. Louis was the first to utilize the Gamewell system which would become the most recognized fire alarm system in the U.S. Around 1900, St. Louis started casting the shell of their alarm boxes themselves, but continued to use Gamewell works inside.34 In 1942 the St. Louis Fire Department was reorganized and with this they developed new response assignments. They instituted new “run cards” with a fifth alarm assignment.35

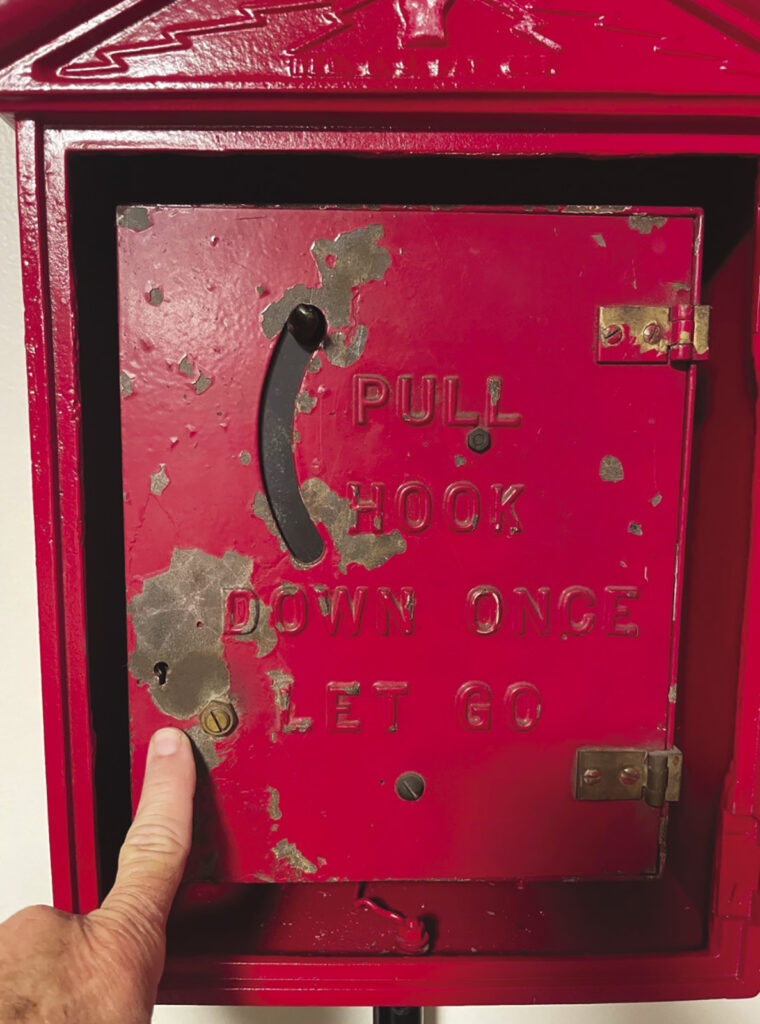

As we have learned, the first fire alarm telegraph box system was installed in Boston by Dr. Channing and Farmer. The first fire alarm telegraph boxes were accessed by opening the door to the street box and turning a hand operated crank. By turning the crank, a code wheel turned that had high points on it corresponding to the box number, these points moved a “hinged lever up and down against a spring tension, opening and closing the circuit by contacts at the lever’s end.”36 Thus transmitting an electromagnetic signal via telegraph wires to a central station that would operate a corresponding signal to the alarm center which would pull and release a bell clapper making an audible ring identifying the box. The first activation of the system by a citizen occurred on “April 29, 1852. Unfortunately, the helpful citizen cranked too fast, such that the message could not be read, and the man had to run to the central signal office to alert them of the fire in person.”37 The first alarm system was a work in progress and adaptation were made to solve problems like this. A “reduction gear” was added that made it necessary to turn “the crank handle…several times to get the code wheel around once.”38 Other issues were that the original hand crank boxes had to have the crank turned in a clockwise rotation to send a signal, and in the excitement of a fire sometimes a person would turn it the wrong way. To prevent this boxes were retrofitted “with ratchet devices which prevented counter-clockwise turns.”39 At first the simple operation of turning in a fire alarm was confusing to the citizen. An early prototype box had a paper attached to the inside door of the box that contained “more than 300 words” on how to operate the box.40 This would lead over time to the more simple method of opening a hinged door and pulling down a hook one time to activate a spring driven, clockwork like controlled mechanism to transmit an alarm.

Where’s the Key, False Alarms, and Changes

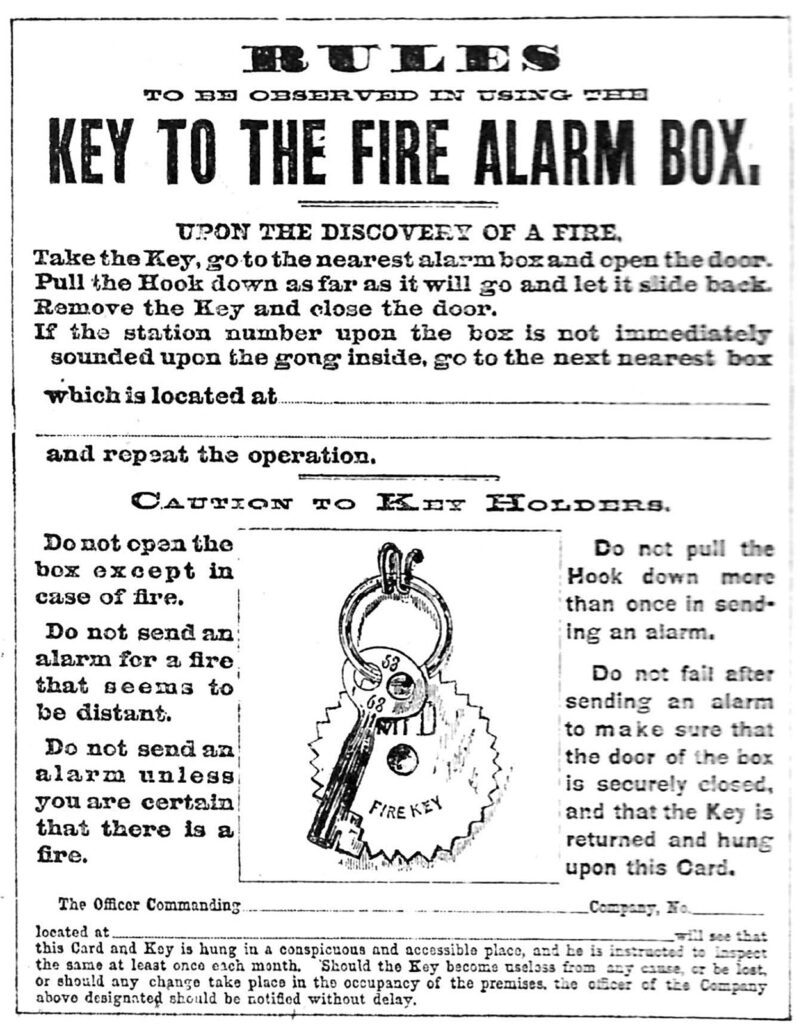

Early on in the concept of using a fire alarm telegraph box system was the concern for the security of the fire box and that it be used only by a responsible party to turn in a verified fire alarm. Basically a concern over false alarms, or vandalism. A variety of ideas were conceived to address these perceived problems. These included “various steps such as keeping the keys in the houses or stores, giving out numbered keys, and using a trap lock.”41

When a locked fire alarm box was installed, keys were issued to a nearby responsible businessman or home owner. Also a number of keys could be given out to influential citizens, or other public officials. On the fire alarm box there would be a list of where a local key could be obtained. Or, in some cities “a conspicuous sign on the pole” where the box was installed provided instructions on reporting a fire and where the key was located.42 In some communities the key holder was responsible for confirming the fire before activating the alarm. In other cases the boxes were installed with “a device which handcuffed the person turning in the alarm. Others developed small booths from which the person could not leave after sending an alarm. From handcuffs or booths, release came only when firemen arrived to free them.”43 All these methods deterred people from sending an alarm and defeated the quick alert and location advantages of utilizing a local fire alarm telegraph box system. Eventually most communities were to move to a simplified, accessible box. Because of the locked box/key system a variety of styles of alarm box keys with varies engraved alarm identification tags can be found in antique stores or on the internet. These early authentic keys with verifiable provenance are highly unique and collectible antiques.

As can be seen the fire alarm telegraph system and components, especially the street boxes, changed over time as new improvements came about and additional procedures adopted. Because of these changes, street boxes were either retrofitted or completely changed out. The very early boxes are much harder to find and highly valued. Also, despite Gamewell having the majority of the market, there were a substantial number of other companies or communities manufacturing their own systems (despite patent restrictions) which adds to the variety of styles of fire alarm boxes. So there is a plethora of various configurations, designs, and wording found on antique alarm boxes. Even Gamewell changed their identifying marks on boxes. Starting with a simple year date, Gamewell went to a tilted hand holding lightning bolts, to a straight hand with lightning bolts, to adding wording with the logo. Though it helps date Gamewell boxes, the number of changes in them and others makes it difficult to properly cover in a short history article. There are some reference books listed near the end of this article that can be used to assist the museum curator or serious collector in determining manufacturers, dates, and the rarity of some boxes and equipment.

Components and Operation of the Fire Alarm Telegraph System

One tends to think only of the red fire alarm call box on the street corner when the vintage city fire alarm systems are mentioned, but to make the total system work there was a variety of other components depending on the design of the system. In this section we will briefly cover some of the components of a fire alarm system and their function.

Street Signal (Call) Boxes

The street signal box is the starting point where the citizen can turn in the alarm for a fire, usually by the simple pull of a lever. A vintage Gamewell catalog describes this alarm box as:

street signal boxes are of cast iron, cottage shaped, and contain clockwork, with spring or weight motors, so arranged as to operate a circuit-breaking wheel to open and close the electric circuit, in which the box is placed a definite number of times at certain intervals, indicating its number upon the alarm-bells, gongs, and whistles and thereby indicating the exact location or number of the box in action. All boxes are arranged to repeat the station number as often as may be required. Three rounds of the box number are generally regarded as sufficient.44

Original street boxes were made of cast iron and extremely heavy. This is one of the reasons that many times the exterior box was locally made for a city installation instead of shipped from the factory. Around 1926, Gamewell began die casting boxes out of aluminum alloys, Gamewell’s new alloy boxes being called Herculite (aluminum silicate).45 Over the years the street boxes were changed and had a variety of features, including various locks and door access.

Station Alarm Apparatus – Bell or Gong

This term is used for the fire station alerting mechanism commonly called an alarm gong (bell). It is used to alert the firemen to a call by the striking the gong with the number sequence sent by the street signal box. Gamewell literature describes the alarm gong as “powerful enough to awaken men if asleep.”46

A vintage Gamewell catalog describes this component as:

We term all our alarm apparatus electro-mechanical, for a very important and distinguishing feature of it is that we require but a minimum amount of battery power to control an unlimited amount of mechanical force. Our Excelsior gong is made in five sizes, ranging from 6 inches to 18 inches. This gong is by far the most reliable and efficient signal gong for sounding a definite number of blows ever produced.47

As seen the gong came in various sizes and was of a flattened dome shape made of a highly polished brass. The gong itself usually protruded from an ornate wooden box that held the striker and actuator mechanism. Alarm gongs are highly valued for museum displays and by collectors. The item is especially prized if it is still attached with the wooden case that would have hung on the fire house wall.

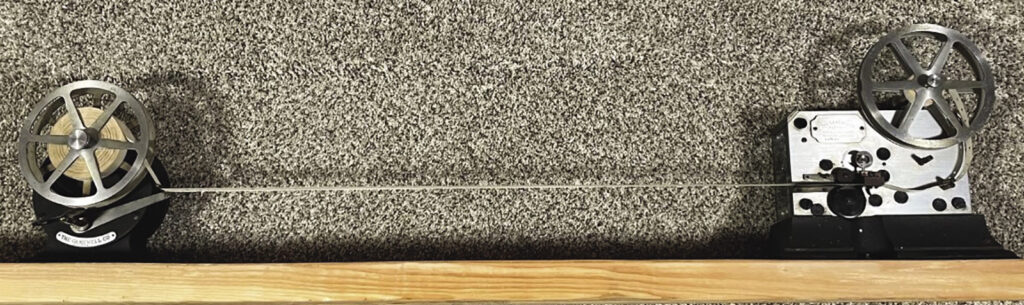

Pen or Punch Registers

Part of the Central Office equipment, and sometimes in the fire station, were the registers which provided a visual indicator of the number of strikes (rings) of the bell/gong that indicated the street call box number.48 This was done on a spooled paper tape that ran through a register that marked the paper either using an ink stylus (pen) or perforated punch. The accounts seem to indicate that the pen registers were not as reliable and the more common over time became the punch register. If the box was 131, the fire watch would see one punch a space, then three punches in a row, and then a space followed by one punch, for 1-3-1. A small take-up reel was used to wind up the punch tape to save as a record of the alarm. If the officer did not catch the ring sequence of the alarm apparatus (gong), they could simply look at the tape and interpret the punch sequence. An optional component that provided a similar resource to this was the visual indicator box.

The register, supply reel, and take up reel were usually mounted on a desk in the alarm or watch office. Collectors may find them mounted together on a single board for display.

Visual Indicator

An option to the simple Alarm gong and or punch register was the visual indicator that could also incorporate a gong or vibrating bell. A vintage Gamewell catalog describes this component as:

Visual Indicators automatically display in plain figures the numbers of all boxes from which alarms are received. They are perfect and reliable in operation, and their use obviates the mistakes which are liable to occur by miscounting blows on bells or gongs.49

The visual indicator had number plates on a chain drive that rotated to bring up the correct number sequence to indicate the street call box number in numeric numbers. Again for example, box 1-3-1, the watch would hear the bell ring out the alarm and could look up and see in the indicator window the numbers 131. This fire alarm component was not as common and is harder to obtain by museums and collectors.

Manual or Automatic Repeaters (Transmitters)

Repeaters were used at the central station where the street box signal would be received. The repeater was used to re-transmit the alarm to the initial and/or other fire stations depending how it was set up. Automatic repeaters were activated by the system and required no human intervention, while manual systems required a dispatcher initiate the re-transmit of the signal.50 Repeater system could be used to make sure the initial responding station heard the alarm, and/or alert other fire stations that a fire call was occurring and at what location. Depending on the protocols for the department this could send additional apparatus or move up equipment depending on what alarm sequence was transmitted. This was the beginnings of pre-planned or automatic dispatch.

Whistle-blowing Machines and Bell Strikers

Gamewell also partnered with other companies and offered a number of options to meet local needs or protocols. These could be hooked to the telegraph fire alarm system and actuated manually or automatically. These included whistle blowing machines or bell strikers to help sound the alarm to the community and/or volunteer fire department. The bell strikers could be used on a dedicated fire bell or used in conjunction with an existing church or government building tower bell.51

Other Equipment and Options

One must remember that the Fire Alarm Telegraph System was just that, a telegraph system and that required wires connecting all components. This involved installing wires throughout the coverage area and their connection through various loops or circuits. In 1877, the New York (Metropolitan) Fire Department headquarters had sixty-five telegraph wires extending from the building “making a circuit of over seven hundred miles within the limits of the city, and connecting with the station houses, the alarm boxes, and the lookout towers.”52

A more advanced piece of equipment of the Central Office was the Annunciator Board, “on which the operator, by pressing numbered buttons, throws into plain view the numbers of the companies which have left their houses to attend the different alarms, and as fast as these companies are released from duty the Central Office is notified by the signal code and the operator at once restores the corresponding annunciator drop.”53

Other instruments at the central station could include galvanometers, power supplies, batteries, Wheatstone bridges and clocks.

Gamewell came up with and offered for sale many options that worked with the fire alarm telegraph system. One of these more unique options was an electromechanical device to speed the response back in the day of the fire horse. When the alarm came in the device was activated and “automatically caused the chains across the horse stalls to drop.”54 This allowed the trained fire horses to leave their stalls and gallop to position under the hanging quick hitch harnesses to be quickly hooked to the fire apparatus and respond.

How a Typical Fire Alarm Worked

In this section we will cover a composite general description of the operation of a historic fire alarm telegraph system. Depending on the city, the time period, and the installation or retrofit of the system, the activation and response may have varied. We greatly appreciate and acknowledge the contribution of Fire Chief (RET.) Darryl Kerley, from Oak Ridge and Seymour, Tennessee, in sharing his knowledge of the historic fire alarm telegraph systems. Chief Kerley in his career has served in volunteer, municipal, and industrial fire departments, and has experience providing fire protection for a Manhattan Project Facility where the original Gamewell system was still in use. This intimate knowledge and additional historical research has provided him with a unique and knowledgeable perspective on fire alarm telegraph systems.

Chief Kerley relates the following historical account of a typical activation and response to a fire alarm box call:

The citizen would have gone to the corner pull box station and initiated the alarm by breaking the glass in the front door of the box to open the outside box door and pull down a hook lever. This would have activated a spring wound clockwork like mechanism that would send the alarm. This was done by the spring turning a key code wheel that breaks the circuit contacts on the wheel spaced to give the corresponding box number.

The signal would be sent over telegraph wires to a Central Office or receiving station (now days we would call it the alarm room). The circuit breaks occurring from the code wheel in the box would ring a gong to signal the box number or activate an indicator box (visual indicator with numbers that rotated to show the box number).

The Central Office could then resend the signal to the fire station or other fire stations to notify them of the alarm using a manual repeater or retransmit device by selecting a matching code wheel to the original box and inserting it into the repeater and activating it to send the signal. Usually a city had the telegraph lines divided in a number of “loops” so that if one loop went down they still could send on the other loops. Also they could transmit messages based on one or more loops using the repeater.

The Central Office and each station would have a map, run cards, and/or information carried in an officer’s pocket notebook that gave the location of the box and the corresponding station that was supposed to respond. Run cards also had preplanned assignments for additional alarms and any move ups of companies recorded on them.

The first arriving officer on the scene had a special key to the street call box that would provide access to the inside of the call box to get to a telegraph key where he could signal their arrival and also request additional alarm assignments. Back at the Central Office they could adjust a switch on the repeater or transmit box which would set it for stations to notify them of second or multiple alarm assignments to the box location.

After the fire was out or call completed, the fire officer would take his key and again access the inside of the box to reset the box mechanism, manually rewind the code wheel spring, and then send a signal to the Central Office to clear the alarm (assignment complete and box reset). The Central Office watch would go to their indicator box and pull a lever to reset the number display on the indicator box and also manually rewind its spring. This is where we get the saying: “we’ve cleared the alarm” that is used today to say the crew has completed the assignment and returning to quarters. Back in the day they were literally clearing the alarm box for the next call.

The Central office also had assigned shifts like the fire stations and each shift had someone assigned to oversee the battery bank on which the system would operate for the shift. Typically a two bank, Bank A and Bank B, battery system. The off line battery system would be charging while the on duty battery system would power the telegraph alarm system. An option to the visual indicator box was tape register system (mentioned in previous section). A punch register would punch holes in a spooled paper tape in the sequence matching the box number. This enabled the alarm watch to read the box code location from the paper tape if they missed the number of gong strikes signal.55

Historical Importance of the Fire Alarm Telegraph System

Certainly the most critical importance of the early fire alarm telegraph systems were in the lives and property saved by this new tool in the fire service. The actual contribution to society in lives and communities saved and allowed to prosper over the years is incalculable. Who knows the future contributions these peoples’ lives went on to enhance the success and quality of life in America, as well as the world. Followed by this though is the contributions to fire service operations and procedures that have become part of our history and traditions. In this section we will examine some of these contributions.

The term “Box Alarm” today usually means a one station assignment to a call, i.e. dispatch may say: “Engine 28, box alarm at 124 Maple Ave.” This originated from the fire alarm telegraph days when a station would be assigned to check out an alarm from a street call box.56

The concept of the second, third, or further alarms comes from the fire alarm box days when the second group of stations or apparatus that would be signaled to respond were written on the run card on the second line of the card (being the second alarm), the third group the third line and so on. In the old days requesting a second alarm literally meant they were requesting the apparatus identified on the second line of the run card.57 In the New York (Metropolitan) Fire Department in 1877, the officer requesting a second alarm would tap the telegraph key in the street call box “ten strokes and the number of the box.”58 This would be their signal back to the Central Office requesting a second alarm.

As mentioned in the previous section, the term “Cleared the alarm” comes from the fire officer actually clearing the alarm box by resetting it after the assignment was completed. Some departments still use this term today for when they are clearing the scene returning to quarters.59

Though we don’t normally hear the term “run card” used much anymore, the concept of the run card was the fore-runner to Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD). A card was made up for each street call box number. On the card was the box street address (location) and the initial fire company (Engine) assigned to respond to that box. As mentioned above, the second line on the card had the second alarm assignments and so on. By instituting the run card, the fire department had already initiated the concept of pre-planning their response assignments to each location in the city along with additional needs and moving up of other companies. All the dispatcher had to do was pull the corresponding card and read the information to know what to send on the alarm.

Another term that developed in the days of the street alarm boxes was “Joker”. Though I have heard this term used in several different contexts, it apparently is related to the fire alarm telegraph system. Back in 1907 in his book Fire Fighters and Their Pets, NYFD Secretary Alfred Downes related that the fire house alarm bell was called the “joker”. He said that an old fireman had given the following explanation for the name, “the bell must be so called because, on very rare occasions, it missed a tap, and sent the men and the apparatus out on a fool’s errand. When the signal had not rung in properly the call was a joke on the company.”60 Additional research revealed that part or all of the fire alarm system in some instances had the term “joker” applied. J.E. Peavey in a 1913 article wrote that:

the term, “joker circuit” as applied to a certain class of circuits used in the fire alarm system is a misnomer. The so-called joker circuits are a group of highly important secondary circuits that connect the central fire tower with the local fire engine houses throughout the city, but are not electrically connected with the street alarm circuits. The joker circuits are for the use of the central fire tower telegraph operator, to telegraph alarms to all the engine companies throughout the city. … each circuit contains a telegraph key, line relay, and sounder, and the necessary switches for grouping, or connecting, all of the circuits at the central fire tower.61

Chicago Fire Department’s list of fire service terms defines “Joker Stand” as “the communications center of an older Chicago firehouse which involved the telegraph key, speakers and phones.”62 It appears the origin of the word “joker”, as it relates to the fire alarm telegraph system, is one of those terms whose meaning is obscured in history.

A final bit of trivia, but a significant item. There is no number zero in the numbering system of the fire alarm street boxes. In other words the box numbers contain no zeroes, as there would be no box 10, because there is no way to signal a zero ring on a gong.

The Coming Change in Communications

In our discussions during research for this article, Chief Kerley related that it is fascinating to think about all the intricate design and engineering that had to occur back in the 1800s to create and operate a working fire alarm telegraph system. In its time, the fire alarm telegraph system and the operational procedures that it spawned were cutting edge technology and tactics. It not only saved lives and property but laid the foundation for the future operations of the fire service. However, over the years communications technology would change and at least partially surpass this innovative system.

With the general availability of home and business telephones in the 1950s and 60s the use of or need for a city’s fire alarm telegraph system to communicate fire alarms began to decline. With a readily available phone, the emergency could be called in direct from the residence or location of the fire, along with getting additional information on the emergency direct from the caller.

In current times, the wide spread use of cell phones has replaced in many cases the use of “landlines” and now provides an individual with direct communications from their personal carried communication devise. According to a 2018 Smithsonian article, “an estimated 240 million calls a year are made to 9-1-1. Upwards of 80% of these calls now come from wireless devices.”63 In its time, the modern technology of the fire alarm telegraph system has been surpassed by the newer and more convenient technology of today. Though there are still some cities that maintain at least a portion of their original fire alarm telegraph system, to provide a redundant means of receiving alarms, they are slowly phasing out this technology. Just as fire buckets and man-powered fire pumps were replaced by steamers and horses, they too would be replaced by motorized fire apparatus accompanying the technology change in transportation. And so too has fire alarm technology developed to meet a need, changed over time, and then transformed with modern communication methods. However, the fire alarm telegraph has left a lasting legacy in the fire service through the terminology and protocols we still base modern emergency dispatch and response on today.

Resources and a Word of Caution

For the Museum Curator or Conservator, as well as the fire service buff or collector, there are a number of resources that can be of use in identifying the historical significance, manufacturers, and dates of fire alarm telegraph components. Among these are two books: Fire Alarm, The Fascinating Story Behind The Red Box On The Corner, by Paul Ditzel, published in 1990; and History of the Fire Alarm and Police Telegraph, by Paul C. Roncallo, published in a limited edition in 2005. Even these well researched works are not the complete definitive resource, but they do provide substantial documented history with corresponding photographs of the various plethora of fire alarm boxes and other components. Other artifacts held in museum collections and archives are original sales and technical literature from the various fire alarm companies that can assist the researcher in identifying components of fire alarm telegraph systems. The Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC and the National Fire Heritage Center in Emmitsburg, Maryland house significant historical fire service artifacts and historical archives in their collections, though somewhat limited in access to the researcher.

A word of caution should be given to the fire museum conservator or collector of fire alarm system components. Once you have assembled a number of components, it is only natural to see if one can make the system work. It should be understood that most original street boxes operated on a closed circuit, and were designed to work on direct current (DC), low voltage, and operated at 100 milliamps.64 One should have appropriate electrical expertise to make sure the all the components match and that insulators and connectors have not deteriorated or worn out. Some later punch registers and bells/gongs operated on alternating current (AC) and 110 volts. Another possibility is a previous restorer/owner may have altered or retrofitted the components over time. The last thing one would want to have is a fire caused by an antique fire alarm system. Also be aware that if you do alter a call box or components you may be affecting the provenance or historical importance of the fire service artifact.

Conclusion

Gamewell Company literature of the late 1800s, indicated that they were already pondering the historical significance of the role of fire alarm telegraph systems.

The loss of a few minutes’ time after the discovery of a fire often means the loss of thousands of dollars’ worth of property, and sometimes human life.65

The history of Fire Telegraph not only shows a rapid progress toward greater certainty of operation, and a multiplication of the functions of the apparatus to meet the demands of 19th century civilization, but every effort that science and ingenuity could apply has been brought to bear on the vital question of saving minutes, and even seconds, in giving alarms of fire, and in enabling the fire-fighting force to more quickly respond thereto.66

Dr, Channing, John Gamewell, and others had set out to use the newly emerging technology of their day to address life safety issues by developing a system for prompt fire alarm initiation, rapid communication, and quick response. This was the forerunner of the enhanced 9-1-1 systems we see being implemented across the United States today, whereby we are using modern technology to successfully address life safety needs.

In establishing the fire alarm telegraph system and the response procedures it created, these visionaries inaugurated techniques that laid the framework of the fire service’s operations today. Some of the rudimentary protocols and terminology still remain in our fire service lexicon today.

Functional displays of early fire alarm telegraph systems are highly valued by fire museums in being able to visually represent the important role these systems contributed to life safety and the development of the operations and traditions of America’s Fire Service. Even partial displays key the interest of many visitors as to the historical significance of the old “red box on the corner.”

The fire alarm telegraph has left a lasting legacy in the fire service through the terminology and protocols that would lay the foundation of early fire detection, communication, and rapid response. All this would be an important step in the continuing development of the operational procedures that have become a part of the rich history and traditions of the American Fire Service.

Author’s Comments:

The author wishes to recognize and thank the fire service personnel and organizations for their assistance in the development of this article. In particular, the author expresses his appreciation to: Fire Chief (ret.) Darryl Kerley for sharing his expertise and knowledge of fire alarm systems; also, our appreciation to the University of Missouri Ellis Library/Lending Library for assisting the author in obtaining the inter-library loan of various research documents and archival materials.

Photos

All photos are credited within captions.

* Rules, Key to the Fire Alarm Box – Image from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine article “The Life Of A New York Fireman”, Vol. 55, No. 329, 41, October, 1877, p. 668. Considered to be in the Public Domain.

Endnotes

1. Timothy Winkle, “This is 9-1-1. What is your emergency?”: A history of raising the alarm”, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Web article: https://americanhistory.si.edu/ar/node/47196 , published February 15, 2018.

2. Dennis Smith, History of Firefighting in America, 200 Years of Courage, Dial Press, NY/NY, 1978, p. 4.

3. Herbert Theodore Jenness, Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present, Cambridge, Mass, 1909, p 2.

4 Smith, p. 5.

5 Jenness, p. 5.

6. Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Industrial Revolution”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 13 Mar. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution. Accessed 12 July 2022.

7. Clare D. McGillem, “Telegraph”, Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/technology/telegraph. Accessed 12 July 2022.

8 Ibid.

9. Paul Ditzel, Fire Alarm, The Fascinating Story Behind The Red Box On The Corner, Publisher Fire Buff House Division of Conway Enterprises, Inc., New Albany, IN, 1990, p. 16.

10. Ibid, p.15.

11 Ibid, p.16.

12 Ibid.

13. Paul C. Roncallo, History of the Fire Alarm and Police Telegraph, M.T. Publishing Company, Inc., Evansville, IN, 2005(limited edition 397 of 1000 copies), p. 11.

14 Ibid.

15 Ditzel, p. 24.

16. Roncallo, p. 11.

17 Ditzel, p. 24.

18. Roncallo, p. 11.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ditzel, p. 24.

22. Roncallo, p. 10.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid, p. 11.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid. p. 12.

30 Ibid, p. 17.

31 Ibid, p. 6.

32 Ibid, p. 8.

33 Ibid, p.9.

34 Ibid, p. 41.

35. Bill Westhoff, “History’s Corner: The St. Louis Fire Department Justifiably Proud”, FFAM Magazine, Warrenton, MO, May/June 2018, and A Tribute to the Fire Service of Missouri, Walswoth Publishing, Marceline, MO, 2018, p. 119.

36 Roncallo, p. 9.

37. Timothy Winkle, “This is 9-1-1. What is Your Emergency?”: A History of Raising the Alarm,” Smithsonian Institute, National Museum of American History, Feb. 15, 2018, web article: https://americanhistory.si.edu/ar/node/47196 , Accessed July 14, 2022.

38 Roncallo, p. 9.

39 Ditzel, p. 20.

40 Ibid, p. 13.

41. ”The Development of the Fire Alarm Box”, Fire Engineering, Nov. 19, 1924, web archive article: https://www.fireengineering.com/fire-prevention-protection/the-development-of-the-fire-alarm-box/#gref , Accessed July 14, 2022.

42. William H. Rideing, “The Life Of A New York Fireman”, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 55, No. 329, October, 1877, New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, p. 668.

43 Ditzel, p. 37.

44. Fire Alarm Telegraphs 1855-1897, The Gamewell Fire Alarm and Telegraph Company, Gallison and Hobron Company Catalog Makers, New York, 1897, p.16.

45. Roncallo, p. 77.

46 Gamewell, “Fire Alarm Telegraphs”, p. 21.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid, p. 15.

49 Ibid, p. 21.

50 Ibid, p. 11.

51 Ibid, p. 22.

52. Rideing, Harper’s, “The Life Of A New York Fireman”, p. 668.

53. Gamewell, “Fire Alarm Telegraphs”, p. 14.

54. Ditzel, p. 29.

55. Darryl Kerley, Fire Chief (ret.), DOE, City of Oak Ridge Fire Dept., and Seymoure Volunteer Fire Dept., Tennessee, Telephone interview with the author, July 25 and 27, 2022.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid.

58. Rideing, Harper’s, “The Life Of A New York Fireman”, p. 668.

59 Kerley, Telephone interview.

60 Alfred M. Downes, Secretary of the New York Fire Department, Fire Fighters and Their Pets, Chapter I. “Away They Roll”, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York and London, copyright 1907, Accessed through Google Books July 27, 2022, P. 9 – 10.

61 J.E. Peavey, The Telephone as an Auxiliary to Fire Alarm Telegraph”, in the: Harry B. McMeal, Telephony, The American Telephone Journal, Vol. 65, No. 9, Telephony Publishing Company, Chicago, August 30, 1013, via Google Books July 27, 2022, p. 24.

62 “CFD Definitions”, Chicago City Government, Fire, Website: https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/cfd/supp_info/cfd_definitions.html , accessed July 25, 32022.

63 Winkle, “This is 9-1-1. What is your emergency?”, Smithsonian Institute.

64 Roncallo, p. 207.

65 Gamewell, “Fire Alarm Telegraphs”, p. 9.

66 Ibid, p. 32..