While we have reviewed early American firefighting procedures in previous articles, we are now going to focus on some specific tools of the trade. Fire buckets were a prominent tool used in firefighting during the Colonial era. However, in addition to the bucket, fire brigades or fire societies had many other tools they used as part of firefighting and fire prevention activities. Some of the more common specialty tools included: bells, fire alarm rattles, salvage bags, and firemen’s bed keys. We will review some of these tools and their use from a historical firefighting perspective.

Early Fire Protection

As mentioned, the fire bucket was the major firefighting tool in colonial America. Though not a very efficient means of fighting a fire, the fire bucket provided a means of fire extinguishment using water carried in the bucket and passed by the local citizenry in lines forming a bucket brigade. Buckets were filled at the water source, a town well or stream, and passed hand-to-hand down the line to the fire where the water was thrown on the flames. Empty buckets were passed back down an adjoining line to the water source to be refilled again and the process continued. Later developments included the addition of the first fire engines and hand-operated pumps. Though they did a somewhat better job of putting the water on the fire, the engine’s water box had to be filled still using a bucket brigade.

From almost the founding days of the first settlements in the American Colonies, fire became a major threat to survival. The Jamestown settlement was established in May of 1607, and after devastating hardships to the original settlers in the early months, new colonists and supplies arrived in January 1608. Unfortunately, shortly thereafter “the first recorded fire in America occurred when the community blockhouse caught fire. Nearly every building in America’s first settlement was destroyed in that first year.”1 A similar incident occurred in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1623 nearly devastating the three-year-old settlement. According to Governor William Bradford, the fire occurred in cold weather when a fire in a fireplace “broke out the chimney into the thatch, and burned down 3 or 4 houses, and consumed all the goods and provisions.”2 Thatch was a straw material that was dried and bundled and used as a roofing material. Also, in those days in Europe and America, the chimneys were of wood construction and lined with mortar or mud to make them somewhat fire-resistant. Because of this chimney and roof fires were a major cause of conflagrations in early colonial days.

Because of the threat from these types of fires, Boston passed an ordinance in 1631 in which “wooden chimneys and thatched roofs were strictly forbidden. Also, chimneys had to be swept regularly to keep them clear of dangerous wood tar.”3 Thus began some of the first fire prevention regulations. The Governor of New Amsterdam (New York), Peter Stuyvesant, took it a step further in 1648, not only banning wood chimneys and thatched roofs, but instituting fines that helped purchase “ladders, hooks, and buckets.”4 The ladders were used to gain access to roof fires, and the hooks with ropes were used to pull down burning roofs and buildings. In addition, a night watch was established to watch for fires during the night when a fire could most likely go unnoticed until it became a significant fire that would be hard to extinguish. These fire watches that patrolled the streets were first called “Prowlers.”5

Sounding the Alarm

Originally there was little formality or procedure when a fire broke out, “the person discovering a fire ran to the nearest neighbor for help, and from one to another, the alarm would loudly be given, and all started with their buckets.”6

Hand-Held Bells

In early Colonial America, church bells were imported from England until 1736 when the first bell was cast in Fairfield, Connecticut.7 Initially local “blacksmiths made iron cow and other hand bells for farm and other purposes.”8 Before large fixed bells were available in community churches and/or public buildings in colonial America, a variety of alarm devices were used to alert people to fires. Even after the church bells were available in the community these early devices were in some cases still used for signaling the initial alarm. Initially, the human voice calling “Fire!,” followed by “Throw out your buckets” alerted the citizenry to a fire.9

In New Amsterdam (New York) in 1697 a night watch was established for general safety they carried a handbell that rang as they called out “each hour of the night.”10

So it appears this may be the early concept that led to a nightly fire watch. In some towns and settlements, the town crier also became the fire watch, signaling the first evidence of fire with their handheld bell.

As mentioned, handbells were used in a variety of situations from town criers to calling school in session in the early colonies. They continued to be used as household and school bells into the early 1900s, so finding an antique brass handheld bell is fairly common. They were made by various artisans and manufacturers and varied in size and design. An example handheld bell is made of a turned wood handle (yoke) with brass fittings or canons, a brass bell-shaped housing, and a brass or iron clapper suspended inside the center of the bell. The general size is 8” tall, with a base or mouth of the bell 5 and ½” in diameter.

Brass handheld bells are prized by a variety of collectors based on their perceived original use. Because of this, unless there are identifying marks that link a handheld bell to firefighting, it is hard to determine their provenance. Even a school bell might be pressed into use to signal a fire alarm.

Eventually, hand-drawn and horse-drawn fire apparatus would have bells or fire gongs mounted on them to ring the alarm and clear the way for the fire equipment and firefighters. Also, with the development of the telegraph in the 1800s would come the use of fire alarm call boxes to ring out the alarm in the fire department. But these have their own story and chronicle in fire service history.

Muffin Bells

Coming about as a variation in Victorian times in the early to late 1800s, the muffin bell gets its name from the shape of old English muffin pastries and has a distinctive sound. Like other handheld bells, it was used for a variety of purposes, from a general use household bell to boarding houses, to fire watches. Some information relates that it was “often used to sound [a] fire alarm,” it was sometimes used by “merchants wanting to attract customers.”11 The bell is composed of a turned wooden handle with brass fittings, two brass bowl-shaped or muffin-shaped bell halves, and an internal double strike iron or brass clapper. The bell halves are slightly offset in the handle so that the clapper makes a double strike sound by hitting one half first and then the other. This unique two-tone ring makes a distinctive sound that could be easily identifiable from a regular handbell. Because of their general use, manufacturer, and popularity of the time, they are fairly easy to find though relatively expensive antique.

Fire Rattle

As mentioned previously in this article in New Amsterdam Governor Stuyvesant established fire watches that initially were called “prowlers.” These fire wardens soon became known as the “rattle watch” as they carried a wooden rattle noise-making device that was used to sound a loud distinctive rattle to alert citizens to a fire.12 This type of alarm rattle soon spread to many towns as it was cheap to manufacture and could be made by local carpentry artisans. However, the wood rattle was not specifically created as a fire alarm rattle. The wood rattle dates back to medieval times and further to biblical observances by the Jews. Called a grogger it was defined as “a wooden device that when turned around and around produces a noise like a series of knocks, traditionally used during the Jewish festival of Purim was used by the Jews as a noise maker for celebrations.”13 Later it was made and used in the American Colonies by folk artisans as a noise-maker or celebration devise. They would find a new use in the fledgling American fire service. According to the Smithsonian Institute, a variation of the rattle was used in the American Civil War and “commonly made of White Oak or similar wood, were used on ships to call all hands to battle stations.”14 In more recent times it was used during the world wars as a signal for a poison gas attack.

Though the fire rattle varied in design depending on the local artisan who manufactured it, the fire rattle of colonial times usually had some artistic, as well as functional design. A historic example is pictured. It can be described as a wood cog turned by a swinging handle that contacts a wood reed mounted in the main body which makes a loud clacking sound when the handle is swung in an arch above the head. There is a larger bulbous end that holds the reed to add weight to help swing the unit in a circular rotation. Sometimes a brass weight was added to the end to help swing the device in case the wood swelled from moisture. The device is approximately 8” long, 6” high, and 1 and ¾” thick. The handle is usually decoratively turned and the bulbous end may be carved with decorative ridges on the curved sides.

Though the actual use or provenance of an antique rattle is hard to determine without identifying marks and documents, original period rattles are highly prized by collectors and fire museums.

Church or Tower Bells

As churches and public buildings were constructed that could afford tower bells, the practice of using these large bells to sound the alarm was instituted.15 This too led to some success and sometimes not in sounding the alarm. Though it is hard to imagine religious intolerance in the United States founded on freedom of religion, in colonial times the City of New Orleans had a law forbidding the building of any churches except Catholic.16 On Good Friday, March 21, 1788, a fire broke out on Chartres Street. Messengers ran to the Catholic monastery to get them to ring the church bell and sound the alarm for the fire. However, it being Good Friday “an ancient religious decree required that all church bells must remain dumb [silent] throughout the day.”17 The priests standing by the tenets of their order refused to allow the bells to ring. When the fire was over, 857 buildings had burned including the church and monastery.18

A different story regarding a bell sounding the alarm occurred in Chicago during the “Great Chicago Fire” of 1871. The Chicago Fire is remembered today as the annual October date for the United States’ Fire Prevention Week. During the fire, the courthouse bell was used to sound the alarm and continued to be rung until the courthouse itself was engulfed by the fire. The brass bell was later salvaged from the destroyed building and metaled down to make souvenirs including commemorative coins and small replica bells.19

This history of the Chicago Fire and bell may have led to a more modern handheld bell that is cast with the words “Fire Warden 10” and “Chicago” on the exterior waist of the bell. In addition, an engraved name and their service dates may be found on the other side of the presentation bells. These can be found on the internet and were used in some situations as retirement gifts for firefighters and other officials in the Chicago and Illinois area in the 1980s.

According to Arnold Merkitch, author of the book Early Fire Helmets, in the early days of New Amsterdam when church bells or fire tower bells were rung at night to signal a fire “the Watchman in the tower would hang a lantern on a pole and place it out a window pointing to the direction of the fire.”20

Eventually, some cities built specific fire watch and bell towers in the different wards of the city to watch for and sound the alarm for fires. They would play a role in the coming fire alarm telegraph system, but that is another part of fire service history.

Salvage Bags and Bed Keys

Though bucket brigades or hand-operated pump engines were efficient as could be for their time, their ability to put sufficient water on the fire to contain major blazes was limited. Thus once a fire expanded beyond the incipient stage, there was small hope of extinguishing it before it became a major conflagration producing large losses. Many times the firemen quickly estimated their chances and though they valiantly fought the fire they immediately started efforts to save as much personal property as possible for the owner by removing the contents of the house and surrounding exposures. From this, we see the early beginning of the modern-day concept of salvage operations in the modern fire service. Though today we more commonly cover and protect furnishing in place with salvage covers than remove them from the building in salvage bags.

According to fire historian Paul Hashagan, writing about firefighting in Colonial times “the bed key was a small metal tool that allowed the men to quickly disassemble the wooden frame of a bed, quite often the most valuable item owned by a family, and remove it to safety. Other household goods of any value were snatched up, placed in salvage bags, and carried to safety.”21

In 1718 in Boston, the first Mutual Fire Society was established. It operated independently of the engine or firefighting companies. Their purpose was to provide volunteer auxiliary assistance to the regular fire companies. This role consisted of helping evacuate people and save the owner’s possession from the fire by removing them. When the fire alarm was sounded each society member responded “with his own bag and bucket… together with a bed key and screwdriver.”22 Following Boston’s example, American Scientist, Printer, Inventor, and Statesman of the American Revolution, Benjamin Franklin, formed the Union Fire Company in Philadelphia, PA. Franklin wrote in his autobiography that each company member maintain “a certain number of leather buckets, with strong bags and baskets (for packing and transporting of goods), which were to be brought to every fire.”23 Thus again can be seen the emphasis on saving or salvaging a citizen’s possessions even if the fire could not be stopped.

Salvage Bags

Salvage bags of durable material was the most convenient and versatile way to quickly gather up a homeowner’s possessions and remove them from a building on fire or a building that was in imminent danger from a raging fire in the area. Probably at first any handy bag or bed covering was used and bound around items. Over time bags were made specifically for salvage. Because of this, “rolled up in each bucket would also have been a large coarse linen bag used to quickly gather up and remove possessions from a burning structure.”24 Some towns had an ordinance that at least two fire buckets had to be filled with water each night in case they were needed, for fire extinguishment. In this case, the salvage bags would be bundled separately or stored in other/extra buckets.

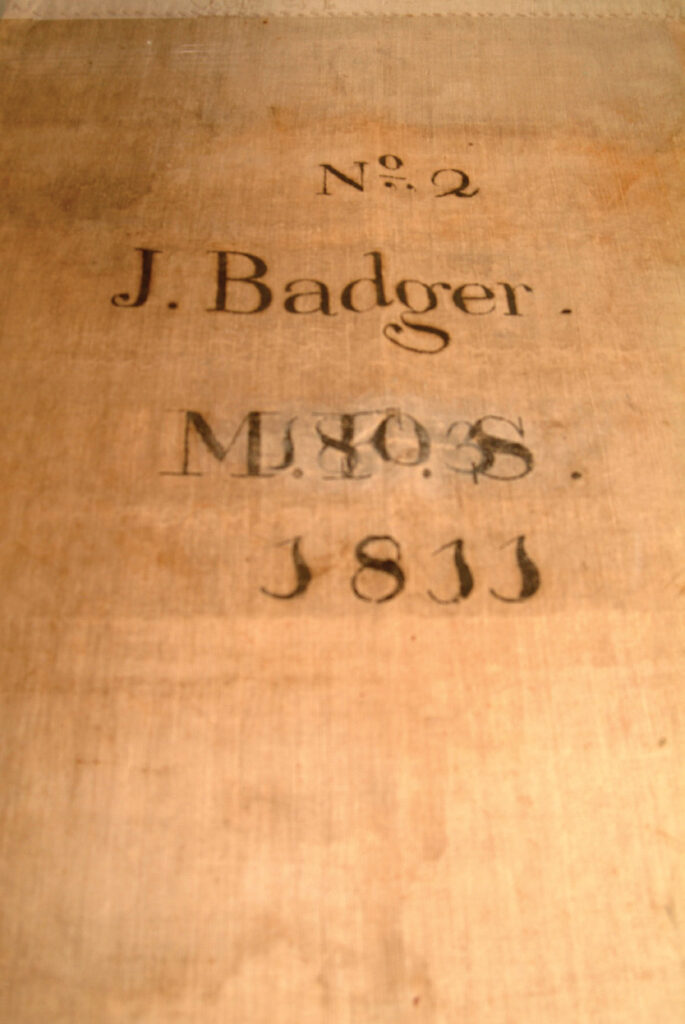

Salvage bags came into use before the Revolutionary War, and were originally hand-sewn of a burlap or linen material. Linen bags commonly had a sewn-in drawstring at the top opening of the bag. For identification purposes, personally owned bags were marked or stenciled with the owner’s name and bag number. Similar to the practice of marking fire buckets. Salvage bags belonging to fire societies or fire companies had their society or company name on them along with possibly an individual bag number for tracking purposes. Bags were made in various sizes over time and no specific standard size was found during research. Some documented historic bags were compared and one salvage bag held by the Smithsonian Institute Museum from ca 1803 was 49 ½ inches by 27 inches.25 Another salvage bag listed by Online Collectibles Auctions had a linen bag marked with a family name and measuring 48 inches by 20 inches.26

Because of the fragile nature of the fabric material through the years and from being used for other purposes over time, original salvage bags from the 1700s and 1800s are rare and are highly valued by fire museums and collectors. Collectors seeking to purchase a historic salvage bag should have it evaluated by a qualified fire service conservator to help identify its authenticity.

Bed Keys

In addition to salvage bags, the firemen’s bed key was an essential tool at the time “because beds were the most valuable pieces of furniture that a family possessed, and after first making sure that all lives were safe, the bed was the next concern of the rescuers. They unbolted the large and heavy beds with wrenchlike keys and carried them out in sections.”27 Firemen’s bed keys were hand forged from iron and formed to provide a multipurpose wrench-like tool for removing square nuts and carriage bolts used in bed furniture, “in the days when their sections were locked by bolts.”28 The Smithsonian National Museum of American History has several bed keys in its non-displayed collection but listed limited information on each. The website WorthPoint lists a tool described as an “Antique Hand Forged Fireman’s Type Square Nut Bed Wrench Key.” It describes the tool as:

18th Century…Made from a single piece of iron bar. The iron bar is forged around a square mandrel and welded together to make the socket end. This form appears to be the standard before the introduction of cast iron bed wrenches. The socket is tapered and can be used on a 3/8” and 7/16” bolt head that is countersunk below the surface of the wood. The tapered slot can be used on a bolt head projecting above the surface. The fork-shaped end is used to loosen slotted cap screw-type bolts.29

The author experimented with an original fireman’s bed key and found it to be a truly versatile device that can be used on a variety of sized square nuts of the period time and to pry and hold carriage bolt heads for disassembly.

Some other Tools

And finally, the early colonial bucket brigades and fire societies used some other utilitarian tools in their valiant attempts to protect their communities from fire. These include hatchets, axes, mops, and ropes with hooks. Though all these tools were fairly common and used in everyday rural life, they had uses at a fire as well. Hatchets and axes could be used for forcible entry as well as remove exposures. Mops wrapped with cloth material and soaked in water were used as swabs to extinguish embers in thatched roofs. Forged hooks attached to ropes could be used to pull off flammable roofing material or pull down walls to remove exposure materials from adding to the fire. Thus preventing fire spread throughout the village from a raging fire.

In Conclusion

The early colonist who filled the role of volunteer firefighters had a challenging task. With limited resources, they made use of what they had to protect their fellow citizens and communities from the ravages of fire. As they learned from their experiences in the new world, they enacted ordinances to make their communities safer and established the early beginnings of fire codes and standards. But above all, these early American firefighters demonstrated the resourcefulness and valiant courage that continues to be the tenets of today’s American fire Fighter. All this would come to establish the rich history and traditions of the American Fire Service.

Endnotes

1. Dennis Smith, History of Firefighting in America, 200 Years of Courage, Dial Press, NY/NY, 1978, p. 1-2.

2. Ibid. p. 3.

3. Ibid. p. 4.

4. Herbert Theodore Jenness, Bucket Brigade to Flying Squadron: Fire Fighting Past and Present, Cambridge, Mass, 1909, p 2.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid, p. 5.

7. Edward T. Howe, Ph.D., Connecticut History, “Early Church Bell Founders”, web article posted January 22, 2020, web address: https://connecticuthistory.org/early-church-bell-founders/ .

8. Edward T. Howe, New England Historical Society, “Small Bells of Connecticut: One Town Made Sounds That Rang in Millions of Ears”, web article 2021, website: https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/robert-hallowell-british-tax-collector-returns-boston-1792/ .

9. Smith, p. 4.

10. A. E. Costello, Birth of the Bravest, A History of the New York Fire Department from 1609 to 1887, Tom Doherty Associates, LLC, NY/NY, Abridged 2002, p. 30.

11. Antiques Associates At West Townsend, Inc., Firefighting, “Antique Alarm Rattles, Fire, Police, Battle, Muffin Bell 19th Century Collection”, Item descriptions, website: https://www.aaawt.com/html/hist_gallery15.html , accessed June 15, 2022.

12. Smith, p.5.

13. Cambridge Dictionary, “Grogger”, Cambridge University Press, 2022, website: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/grogger , accessed June 12, 2022.

14. Smithsonian Institute, National Museum of American History, “Battle Rattle”, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_467373, accessed June 11, 2022.

15. Jenness, p. 5.

16. Morris, p. 70.

17. Ibid, p. 71.

18. Ibid.

19. Urban Remains Chicago, “great Chicago fire “souvenir”, posted January 7, 2015, web article: https://www.urbanremainschicago.com/news-and-events/2015/01/07/great-chicago-fire-souvenir-medal-struck-from-salvaged-bronze-bell-of-osdel-designed-city-hall-1853/.

20. Arnold Merkitch, Early Fire Helmets, Self-published, West Islip, NY, First edition, 1981, p. 64.

21. Paul Hashagan, “Firefighting in Colonial America”, website post Kansas State Fire Fighters Association, http://lishfd.org/History/firefighting_in_colonial_america.htm , accessed June 12, 2022.

22. Morris, p. 27.

23. Ibid, p. 30.

24. Christopher D. Fox, Bonhams Skinner Auctions, “Fire Buckets in 18th Century Boston”, Posted May 7, 2020, https://www.skinnerinc.com/news/blog/fire-buckets-in-18th-century-boston/.

25. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, “Salvage Bag, Badger”, public domain, https://www.si.edu/object/salvage-bag-badger:nmah_1305971 , accessed June 11, 2022.

26. Online Collectibles Auctions, icollector.com, “Early 1800’s Linen Salvage Bag in case of fire” (Joseph Shank), https://www.icollector.com/Early-1800-s-Linen-Salvage-Bag-in-case-of-fire_i10334586 , website accessed 6/13/22.

27. Morris, p. 27.

28. Merkitch, p. 71.

29. WorthPoint, “Antique Hand Forged Fireman’s Type Square Nut Bed Wrench Key”, posted Dec. 18, 2016, website: https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/antique-hand-forged-firemans-type-1845698516.

Photos

All photos by author and from author’s collection, except “Salvage Bag – Badger” courtesy of the Smithsonian Institute National Museum of American History (in the public domain).